Road Safety Manual

A manual for practitioners and decision makers

on implementing safe system infrastructure!

Road Safety Manual

A manual for practitioners and decision makers

on implementing safe system infrastructure!

The goal of The Safe System Approach is that the infrastructure and road environment support a safe outcome for all road users when they make errors, and do so by taking into account human crash thresholds.

Policies, guidelines and programmes need to be developed to ensure progressive advancement towards a network embodying Safe System principles and outcomes. The progressive adoption of Safe System goals and strategies within the operational practice of road authorities requires considerable investment in knowledge, skills, policy and guideline development, both by the road authority as an entity and by individual staff.

More road authorities are recognising the major implications that adoption of a Safe System has. The role of the road authority is to provide a safe network that will require the progressive reduction of the traditional trade-offs that have historically been made between safety on the one hand, and mobility and access on the other. Rather than trade-offs, ‘win-win’ outcomes are required and need to be planned over time.

Support for infrastructure safety investment in order to achieve non-fatal crash risk conditions across the network (the spirit of the Safe System Approach) will become the priority. This is likely to result in substantial increases in the influence of the safety-focused infrastructure compared to other road safety programmes.

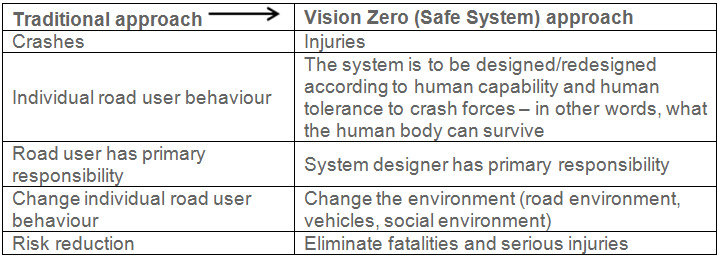

An Example: A comparison from Sweden between the Safe System/Vision Zero approach and a traditional road safety approach as presented in Table 7.1 is instructive.

A New Safe System Focus for Programmes and Projects

Road authorities (and all road safety agencies) have to recognise that the framework for understanding and managing crash risk has to be thoroughly rethought. Existing knowledge of the new framework and responsibilities for determining and responding to crash risk in many LMICs is inadequate.

As an illustration of authorities recognising the need to make this major adjustment, and in doing so, Slovenian road safety authorities (Zajc, 2014) express their new approach as shown in Box 7.2.

The driver was treated like a potential delinquent.

Now: The traffic system must accommodate the driver.

The driver is a victim of the traffic system because she/he has a limited capability for processing all traffic information. The system must be simple so that the driver makes less mistakes. When the driver makes mistakes the system must forgive him and reduce the consequences.

Source: Zajc (2014).

On the other hand, an indicative example of the lack of adequate understanding of crash risk and appropriate good practice responses within the activities of two road authorities is set out in Box 7.3.

Discussions as part of a road safety capacity review were held with the national road authority in a south-eastern European country in 2008 to ascertain, among other issues, why barrier linemarking on a particularly mountainous national road, with a high proportion of truck traffic, was only in place for some 50% of the length required by international overtaking sight distance standards. The response of the authority was that ‘if the full barrier linemarking were to be installed to meet the safety standards, it would mean overtaking opportunities would be very limited’. This trade-off between safety and amenity (or ‘efficiency’ as some would consider it) was not transparent . There had been no community debate about serious crash risk versus faster journey times. It is an all too common example of safety not being fully supported or being covertly traded-off for other purposes in the past.

The approach adopted in Argentina to implement a Safe System focus is explained in the following case study..

Implementing Safe System principles on major new road projects and, particularly, delivering improvement in the safety levels of the existing network over time will require, among other measures, adequate controls on roadside access and roadside activity to be put in place. Necessary powers and government actions to regulate abutting land use development and roadside activities on existing roads for this purpose will be required.

Road authorities and local Governments: Processes to assess the safety impact of any proposed land use development need to be established between the road authority and local governments. Potential safety issues need to be identified, and a range of responses developed as potential development conditions in order to minimise future harm. These processes need to be given authority within land use planning and local government legislation.

Favouring Legislation: Laws to support improved compliance by the public with the decisions of the road authority/local government in these matters will be required, and these need to be enforced. Consideration is required of incentives to be introduced to encourage local government to adhere to their land use planning policies. It is most important that the stakeholders understand and accept the need for legislation to control this development and that the road authority:

Box 7.4 sets out a discussion that addresses a number of highly relevant safety concerns in many LMICs for so-called linear settlements. These common situations reflect inadequate public administration powers (or their lack of application), leading to highly unsafe road environments especially for vulnerable road users.

A major factor in road fatalities in LMICs is vulnerable road users on roads abutting so-called linear settlements. Here, the lack of access control and poorly conceived investment strategies for road networks (and for the development of communities) has resulted in mixed functions with residential and business along the country’s main arterial roads, with heavy, high-speed traffic activity. These ‘coffin roads’ are well-known examples of the problems with linear settlements on busy upgraded roads and occur in many LMICs.

Vulnerable road users are not the only ones at serious risk. Poorly planned U-turn provision or inadequate physical restrictions on U-turns along LMIC highways are a major cause of serious casualty crashes, especially among the passengers of public transport mini buses (e.g. in Egypt). These U-turn gaps and permitted operations are a disaster for road safety. This is a deeply embedded characteristic of the road network in LMICs and requires action across many road authorities in achieving adequate local government development planning to support safe road right-of-way management.

Measures required based on good HIC practice include:

Source: Adapted from Vollpracht (2010).

Linear settlement roads result in unsafe conditions, with pedestrians and vehicles entering and exiting the road from each (continuously) abutting property frontage. Safe System principles indicate that each property entry to a roadway functions as a minor intersection, with the possibility of right-angle crashes involving vehicles entering or leaving the carriageway colliding with vehicles travelling along the road. These situations compromise efforts in many jurisdictions to devise a consistent road classification system applying along lengths of road. A further example highlighting solutions for addressing linear settlements is provided in Box 7.5.

A strategy to address these risks was proposed with two components:

1. An express road system with a 2 + 1 lane cross-section bypassing villages and towns can nearly halve the price for motorways and will be sufficient for traffic volumes up to 20,000 vehicles/day. So the main and safe arterials in Republika Srpska can be built up much earlier than the planned motorway system. They can be widened later, as soon as the traffic volume needs a second carriageway.

2. Adapt the existing main and regional roads within linear settlements to a mixed use function by traffic calming and providing safety for non-motorised users.

Source: Kostic et al. (2013)

As outlined above, unauthorised activities carried out on the roadsides, especially on heavily trafficked routes, need to be regulated and managed to minimise adverse safety impacts for road users. This is an area of considerable weakness in many LMICs, with traders and vendors occupying the road reserve, setting up goods and stalls. In urban areas, traders’ goods and itinerant vendors take over the footpaths, forcing pedestrians to use the road for walking. There is often little management of this unauthorised use by the local government authorities or the police. It is a major challenge for road authorities to obtain the attention of government and gain their support to change the situation. However, there are successful examples in LMICs of local governments negotiating relocations of street vendors to public market spaces, re-established away from the main roads to improve safety.

Adoption of an increasingly safety sensitive road classification for the network that better matches road function, speed limit, layout and design is an important aspiration. As noted above, linear urban development is a characteristic of most LMICs and tends to confound this classification approach. Planning to progress toward the long-term goal of segregation of road use functions and improvement in operating safety is important for Safe System adoption. Suitable planning can guide future road investment (for example in provision of bypass roads) and the associated safety retrofitting of existing roads for their access or distributor functions.

As indicated earlier (see Safe System : Scientific Safety Principles and their Application), the Sustainable Safety approach from the Netherlands places a heavy emphasis on a strong road classification system. Road functionality is embedded in the approach, and it is suggested that roads should have a single function, whether this be as through roads, distributor roads, or access roads. This concept has been well understood for many years, but in more recent years there has been an increased recognition that more needs to be done to ensure this distinction is made. This includes providing an appropriate classification system, allocating all roads to this, and ensuring that the design, and understanding by road users is consistent with this function. Further information is provided on this issue in The Basics: Road user Capacities and Behaviours in Designing Infrastructure to Encourage Safe Behavior, including a discussion on ‘self-explaining roads’ to support road user understanding of this functional classification.