This chapter discusses important new global directions in road safety for low, middle and high-income countries. It charts the establishment of road traffic injury prevention as an international development priority; the adoption of a global target, plan and agreement on the urgent need to scale-up investment in road safety. The paradigm shift to the Safe System is explored further and its promotion by key international development organisations to all countries is noted. Finally, this chapter notes the emphasis in international development being given to encouraging governmental leadership and building the necessary management capacity in order to achieve improved road safety outcomes.

In international development, road safety is being linked with the broader vision of sustainable development through the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDGs are a call to action to end poverty and inequality, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy health, justice and prosperity. Addressing the risk of death and injury in road traffic is fundamental to achieving the SDGs. Within the SDG framework there are two targets that specifically address road safety. However, road safety also has links to many related targets (see Box 2.1)

The SDGs build on decades of work. In June 1992, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, more than 178 countries adopted a comprehensive plan of action to build a global partnership for sustainable development to improve human lives and protect the environment. Member State unanimously adopted the Millennium Declaration at the Millennium Summit in September 2000 which led to the elaboration of eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 11 to reduce extreme poverty by 2015 (UN, 2023)

Previously, international development had a narrow focus on income and spending. However, current approaches promote higher living standards for all, with an emphasis on improved health, education and people’s ability to participate in the economy and society. Development seeks to foster an investment climate, which can encourage increased growth, productivity and employment; and to empower and invest in people so that they are included in the process (Stern et al., 2005; Bliss, 2011a).

While no Millennium Development Goal was set for addressing the prevention of deaths and serious injuries in road crashes to 2015, road safety priorities align with other MDGs, particularly for environmental sustainability, public health, and poverty reduction. As the MDGs era came to a conclusion at the end of 2015, the new year ushered in the official launch of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (WHO, 2023).

In September 2020, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution A/RES/74?299 "Improving global road safety", proclaiming the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, with the explicit target to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by at least 50% by 2030.

WHO and the UN regional commissions, in cooperation with other partners in the UN Road Safety collaboration, have developed a Global Plan for the Decade of Action (WHO, 2021). The Global Plan describes the actions needed to achieve that target. This includes accelerated action to make walking, cycling and using public transport safe, as they are also healthier and greener modes of transport: to ensure safe roads, vehicles and behaviours; and to provide timely and effective emergency care.

The Global Plan outline recommended actions drawn from proven and effective interventions, as well as best practices for preventing road trauma (see Box 2.2). Te various recommendations outlined under each area are designed to support and strengthen the implementation of a Safe System (WHO, 2021).

The Global Plan includes recommendations in the following areas:

Multimodal transport and land-use planning: (8 recommended actions):

Multimodal transport and land use planning is an important starting point for implementing a Safe System. Land use planning must include consideration of travel demand management, mode choice and the provision of safe and sustainable journeys for all, particularly for the healthiest and cleanest modes of transport that are often most neglected: walking, cycling and public transport.

Safe road infrastructure: (7 recommended actions):

Road infrastructure must be planned, designed, and operated to eliminate or minimize risks for all road-users, not just drivers, starting with the most vulnerable. Key elements include developing a functional road classification, minimum technical infrastructure standards and undertaking road safety audits. Infrastructure design must also incorporate speed management to ensure the safety of all road users.

Vehicle Safety: (2 recommended actions):

Vehicles should be designed so as to ensure the safety of people inside them as well as outside. Key actions to improve vehicle safety include the application of harmonized legislative standards to ensure that safety features are integrated into vehicle design to avoid crashes (active safety) or to reduce the injury risk for occupants and other road users when a crash occurs (passive safety).

Safe road user: (4 recommend actions):

Speeding, drink-driving, driver fatigue, distracted driving, and non-use of safety belts, child restraints and helmets are among the key behaviours contributing to road injury and death. The design and operation of the road transport system must therefore take into account these behaviours through a combination of legislation, enforcement and education. Action must also be taken to support safe behaviours through road infrastructure, speed management and vehicle safety features.

Post-crash response: (5 recommended actions):

Efficient post-crash care is critically important to survival: delays of minutes can make the difference between life and death. For this reason it is important to develop systems and mechanisms to ensure appropriate, integrated and coordinated care is provided as soon as possible after a crash occurs as well as the provision of rehabilitation services and comprehensive support systems for victims and their families.

Source: WHO, (2021): Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030

The global voluntary performance targets and indicators adopted in 2017 provide a useful framework to assess progress towards the implementation of this plan

Following a request of the World Health Assembly (WHA) in 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) collaborated with other United Nations agencies and regional commissions and the United National Road Safety Collaborations (UNRSC) to develop 12 voluntary Global Road Safety Performance Targets. Consensus on the targets among United Nations Member State was achieved in 2017.

These 12 targets are shown in Box 2.3 below. Each target represents a specific goal to be achieved at the global level, based on combined efforts of individual countries that wish to contribute to the global objectives. It should be noted that the time horizon for all targets is 2030, except for the first target where it is 2020. The baseline for all targets is 2018.

The Global Plan for the Decade of Action aligns with the "Stockholm Declaration", which is the outcome of the 3rd Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety held in Stockhom, Sweden, in February 2020. The Stockholm Declaration calls for a global target to reduce road traffic deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030 and invites strengthened efforts on activities in all five pillars of the Global Plan: better road safety management: safe roads, vehicles and people; and enhanced post-crash care. It also calls for speeding up the shift to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable modes of transport like walking, cycling and public transport (Government Offices of Sweden, 2020).

Building on the Moscow Declaration of 2009 and Brasilia Declaration of 2015, UN General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions, the Stockholm Declaration is ambitious and forward-looking and connects road safety to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Stockholm Declaration also reflects the recommendation of the conference's Academic Expert Group and its independent and scientific assessments of progress made during the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011-2020 and its proposals for a way forward (see Box 2.4).

A key development was the release of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention (see Box 2.5), which was jointly issued by the WHO and World Bank on World Health Day in 2004 (Peden et al., 2004). The World Report highlighted the growing public health burden and forecasts of road deaths and long-term injury and advocated urgent measures to address the problem as a global development and public health priority. Its findings and recommendations for country, regional and global intervention were endorsed by successive United Nations General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions (UN 2004-2)

Generally, in international development, road safety is being linked with the broader vision of sustainable development, poverty reduction, and the achievement of other worldwide goals. That vision was translated into eight Millennium Development Goals at the beginning of the new millennium. In 2015 the General Assembly of the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Goal 3.6 of the agenda calls for a reduction in the absolute number of road traffic deaths and injuries by 50% by 2020, relative to a baseline estimate from 2010. Target 11.2 aims to provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all by 2030 (UN, 2015).

In preparation for the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety (2011-2020) and its commencement, there was unprecedented agreement from leading international organisations and road safety experts on how to address the road safety crisis emerging in LMICs; the scale of ambitious action required to address this crisis; and the critical factors for successful implementation (Bliss & Breen, 2012; WHO, 2013).

A key development was the release of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention (see Box 2.5), which was jointly issued by the WHO and World Bank on World Health Day in 2004 (Peden et al., 2004). The World Report highlighted the growing public health burden and forecasts of road deaths and long-term injury and advocated urgent measures to address the problem as a global development and public health priority. Its findings and recommendations for country, regional and global intervention were endorsed by successive United Nations General Assembly and World Health Assembly resolutions (UN 2004-2010).

The initiative was followed by the creation of the World Bank's Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF), which supported the development of new road safety management guidelines to assist countries in implementing the World Report's recommendations. The GRSF funded road safety management capacity reviews and the establishment and support of international professional networks. It established a Memorandum of Understanding with iRAP and other international networks such as the International Road Federations (IRF), International Road Traffic and Accident Database (IRTAD), and the International Road Policing Organization (RoadPOL).

Further guidelines on interventions were produced under the umbrella of the newly created United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) which was called for by a UN General Assembly resolution in 2004 (A/Res/58/289). The international Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) was launched providing a key network safety assessment tool for LMICs. The launch of the OECD's Towards Zero report brought together and further reinforced the Safe System and new thinking on approaches to road safety management (OECD, 2008). The highly visible Make Roads Safe campaign and reports were launched by the Commission for Global Road Safety (2006, 2008, 2011) and caught worldwide media attention. Towards the end of the decade, the first ever global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety took place in Moscow, which provided formal endorsement at the highest level of the need for global action. In a series of statements, the Multilateral Development Banks (led by the World Bank) promised a coordinated response for scaled-up investment in road safety management capacity and for road safety to find its place in mainstream infrastructure projects (MDB, 2009, 2011, 2012).

The above mentioned initiatives resulted in the unanimous adoption of a resolution by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010 announcing the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011-2020. This was followed by the launch of a Global Plan produced by the UN Road Safety Collaboration in 2011 (UN, 2010a; UNRSC, 2011a).

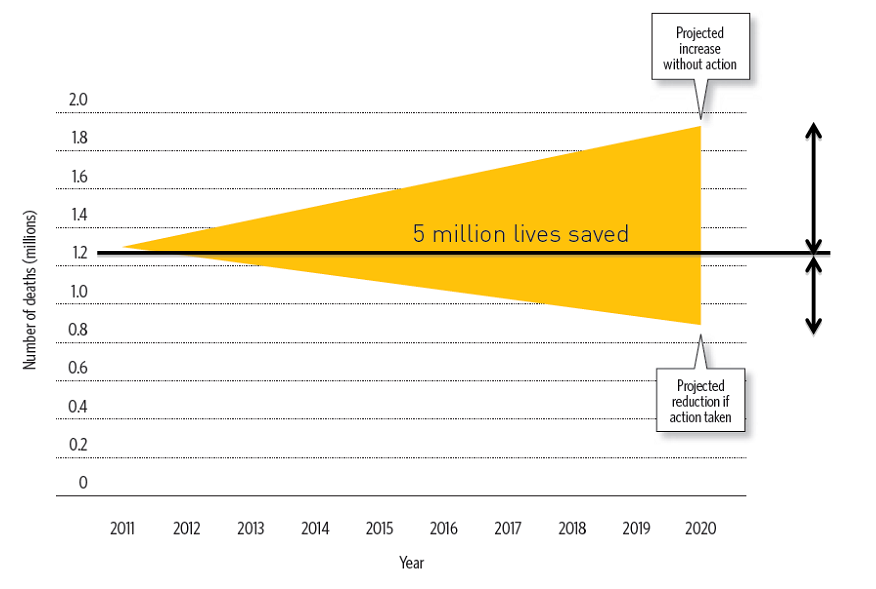

The goal that was set as part of the first Decade of Action aimed to stabilise and then reduce forecast road deaths by 2020 (WHO, 2013). This represented an estimated saving of 5 million lives (Figure 2.1) and 50 million fewer serious injuries, with an overall benefit of more than US$3 trillion (Guria, 2009).

Figure 2.1 Goal of the first Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 - Source: Adapted from Guria, (2009); WHO, (2013).

The Global Plan for the first Decade of Action adopted the Safe System approach and recommended that countries work within the five pillars of action, as summarised in Box 2.1. National road safety performance is monitored at an international level and periodic status reports are published by the WHO (WHO, 2009, 2013, 2015, 2018).

Pillar 1: Road safety management

This pillar highlights the need to designate a jurisdictional lead agency to develop and lead the delivery of targeted road safety activity and to provide capacity for this and related multi-sectoral coordination, which is underpinned by data collection and evidential research to assess countermeasure design and monitor implementation and effectiveness (see The Road Safety Management System )

Pillar 2: Safer roads and mobility

This pillar aims to raise the inherent safety and protective quality of road networks for the benefit of all road users, especially the most vulnerable (e.g. pedestrians, bicyclists and motorcyclists). This will be achieved through the implementation of road infrastructure assessment and improved safety-conscious planning, design, construction and operation of roads (see Road Safety Management of this manual).

Pillar 3: Safer vehicles

This pillar encourages universal deployment of improved vehicle safety technologies for both passive and active safety through a combination of harmonisation of relevant global standards, consumer information schemes, and incentives to accelerate the uptake of new technologies.

Pillar 4: Safer road users

The aim of this pillar is to encourage the development of comprehensive programmes to improve road user behaviour, and sustained or increased enforcement of laws and standards, combined with public awareness/education to increase seat belt and helmet wearing rates, to reduce drink-driving, speed and other risk factors.

Pillar 5: Post-crash response

This pillar targets increased responsiveness to post-crash emergencies and improved ability of health and other systems to provide appropriate emergency treatment and longer-term rehabilitation for crash victims.

Source: UNRSC, (2011a).

Experience with regional targets indicates that they can play an important road safety role and provide a focus for regional and national intervention (ETSC, 2011). (see Box 2.2 and Box 2.3; UN, 2010b, UNRSC 2011b).

Asia and Pacific Region:

The Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) developed regional road safety goals, targets and indicators for Asia and the Pacific as a follow-up to a Ministerial Declaration on Improving Road Safety. At subsequent road safety expert group meetings in 2009 and 2010 these goals, targets and indicators were further defined in order to align with the targets and indicators of the Global Plan of Action for Road Safety 2011-2020. Subsequently, ESCAP has resolved to develop a regional plan of action in line with the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030 and related Global Plan.

European Union:

Regional goals and targets have been set by the European Commission. These are that by 2050, the EU should move ‘close to zero fatalities’ in road transport and target halving road deaths for the interim by 2020. The EU has reaffirmed its ambitious long-term goal, to move close to zero deaths by 2050 with new intermediate targets to halve the number of fatalities and - for the first time - also the number of serious injuries on European roads by 2030, from a 2020 baseline. While highly ambitious aspirations, these are very important statements that road safety must have a priority status if EU countries are to continue to lead in global road safety, as desired by all the EU institutions.

Eastern Mediterranean Region:

Currently, more than 80% of countries in the Region report having an agency which leads national road safety efforts. In only 10 countries, lead agencies are funded and in seven countries they are fully functional in terms of coordination, legislation, monitoring and evaluation. Road safety strategies are present in about 80% of countries in the Region. Eleven countries have one national strategy while four countries have multiple strategies. In 52% of countries the strategies are partially or fully funded. Targets on fatal and non-fatal injuries exist in the strategies in 43% and 24% of countries, respectively.

Regions of the Americas:

The Pan American Health Organization in 2011 announced a Plan of Action on Road Safety with guidelines for Member States. The plan will help countries of the Americas meet the goals of the global Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020.

Sources: ESCAP, (2015); EC, (2011a, 2011b, 2020); WHO (2013, 2015)

The Second African Road Safety Conference held in 2011 was organized by the UN Economic Commission for Africa, the Sub-Sahara Africa Transport Policy Program (SSATP) and the Government of Ethiopia, in collaboration with the International Road Federation (IRF), the African Union Commission (AUC), the African Development Bank (AfDB), and the World Bank. The objectives of the conference were to:

(i) examine and validate the African Road Safety Action Plan that would serve as a guiding document for the implementation of the Decade of Action;

(ii) propose and validate a resource-mobilisation strategy and a follow-up mechanism; and

(iii) learn from good practice and share experiences.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) requested that SSATP write the Road Safety Policy Framework to underpin an African Road Safety Action Plan, which was approved by the Ministers of Transport and vetted by the Heads of State in January 2012. The plan is organized around the five pillars of the Global Plan and aims to reduce forecasted fatalities for 2020 by 50%. This involves stabilising the number of deaths at 320,000, then gradually reducing them to 270,000. If the target is met, more than 1 million forecasted deaths and 10 million serious injuries will be prevented, with a social benefit of around US$340 billion.

Pursuant to the recommendations of the African Union Specialized Technical Committee on Transport, Transcontinental and Interregional Infrastructure, and Energy (STC-TTIIE) meeting in Cairo in 2019, UNECA and AUC formulated Africa's post-2020 Strategic Directions for Road Safety and prepared a draft of Africa's Road Safety Action Plan for the decade 2021-2030.

Taking not of these initial strategic directions, and the UN Resolution A/RES/74/299 "Improving global road safety", the STC-TTIIE adopted an updated versions of the "Strategic Directions for the post-2020 Decade: African common position" with the target to reduce road deaths and injuries by 50% by 2030 as well as to promote the implementation of the Safe System approach. The STC-TTIIE requested AUC to finalize the Action Plan in collaboration with ECA, taking into consideration the Global Action Plan for the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety.

Source: African Union, (2011, 2022).

National target-setting in road safety is an international success story. Setting challenging but achievable quantitative targets towards the Safe System goal in order to eliminate death and long-term injury has been identified as international best practice (OECD, 2008). Until sufficient management capacity and performance data are available in LMICs to set meaningful national targets, countries are advised to adopt the long-term Safe System goal and target reductions in specific corridors and areas using survey data of infrastructure safety quality (e.g. Road Assessment Programmes) and safety behaviours (e.g. speed, crash helmet and seatbelt use, drinking and driving). Full discussion and detailed guidance on national target-setting and the development of targeted strategies, plans and projects is provided in Targets and Strategic Plans.

Progressive shifts in road safety thinking and practice have taken place since the middle of the last century. As outlined briefly in Scope of the Road Safety Problem, an increasingly ambitious approach has been identified, which has culminated in the Safe System goal of eliminating road crash deaths and serious injuries (Peden et al., 2004; OECD, 2008; GRSF, 2009).

In the 1950s and 1960s, rapid motorisation took place in many OECD countries, accompanied by increasing numbers of road deaths and serious injuries. At that time, the emphasis in policy-making was on the driver. Legislative rules and penalties were established, supported by information and publicity, and subsequent changes in behaviour were expected. As experience has shown, it was wrongly believed that since human error contributed most to crash causation, educating and training road users to behave better could address the road safety problem effectively.

During the 1970s and 1980s, a systems perspective on interventions was evident. William Haddon, an American epidemiologist, developed a systematic framework for road safety based on a disease model that comprised infrastructure, vehicles and users in pre-crash, in-crash and post-crash stages (Haddon, 1968). Central to this approach was the understanding that the exchange of kinetic energy in a crash leads to injury, which needs to be managed to ensure that the thresholds of human tolerances to injury are not exceeded. This broadened the scope of intervention to highlight the need for system-wide delivery.

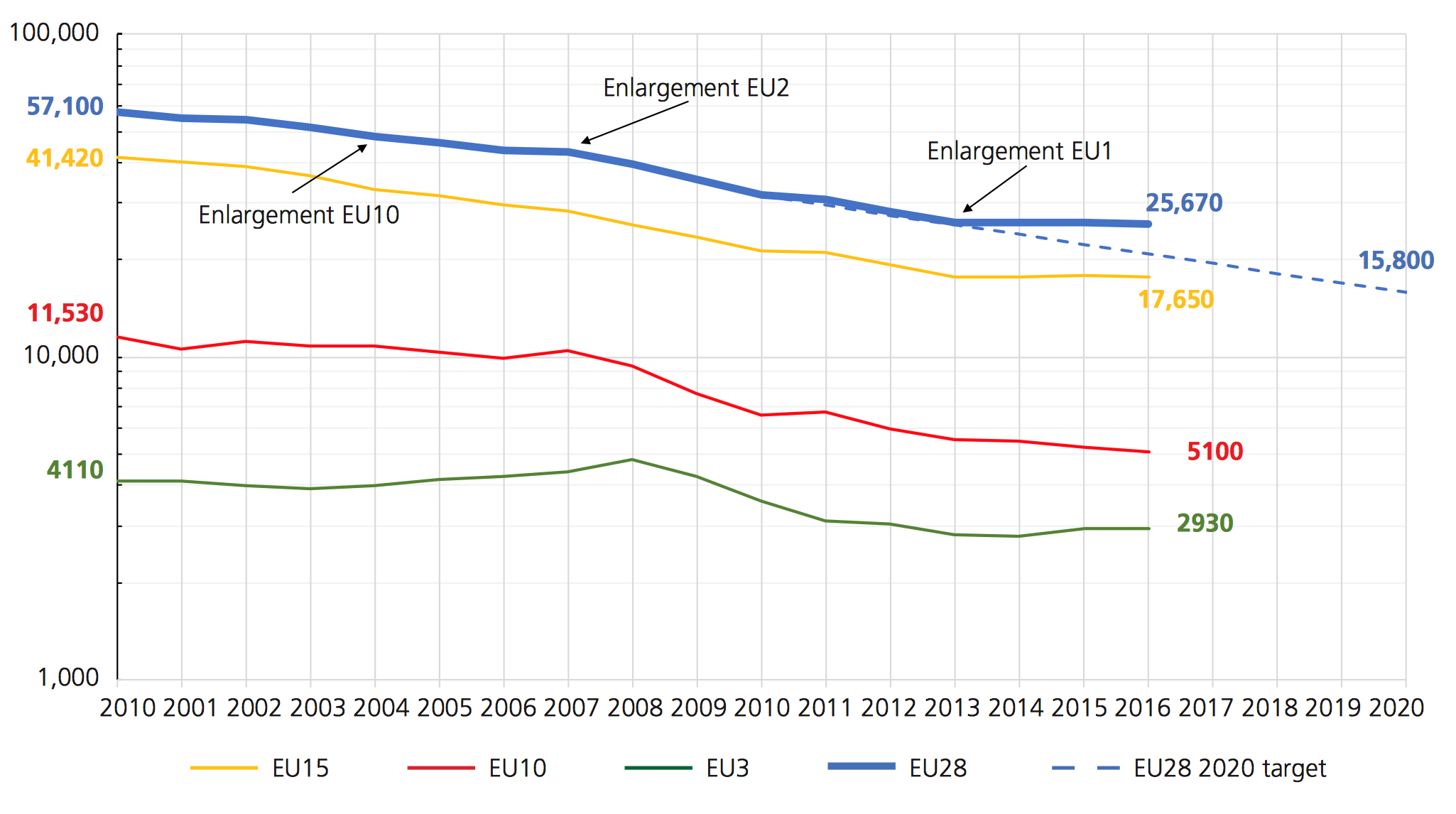

By the early 1990s, countries achieving good results had progressed towards implementing action plans with quantitative targets to reduce death and sometimes serious injuries (OECD, 1994, 2008; PIARC, 2012). The reductions achieved in different groupings of EU countries are presented in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2. Reduction in road deaths for different combinations of EU countries since 2000 – Source: ETSC (2017).

The 28 European Member States reduced the number of road deaths by 19% between 2010 and 2016, however, a reduction in progress had to be registered in recent years (ETSC, 2017). In many countries, casualty reductions have been achieved through system-wide intervention packages. Typically, four broad categories of interventions were responsible for the majority of safety gains achieved. These are:

By the late 1990s, two of the world’s best performing countries had determined that maintaining continuous improvement in performance would require a more ambitious, comprehensive and sustainable approach than had been adopted in previous practice. The Dutch Sustainable Safety and Swedish Vision Zero strategies aimed to make the road system intrinsically safe (Koornstra et al., 1992; Tingvall, 1995; Wegman & Elsenaar, 1997).

In both the Sustainable Safety and Vision Zero approaches, new emphasis is given to managing the exchange of kinetic energy in a crash to ensure that the thresholds of human tolerances to injury are not exceeded. Road deaths and serious injuries are no longer seen as a necessary price to be paid for improved mobility (Tingvall & Haworth, 1999).

The Safe System approach goes further than traditional approaches that focused on safer vehicles, safer roads and safer users. This newer approach now also addresses the critical interfaces between them. The ‘engineered’ elements of the system, i.e. vehicles and roads, can be designed to be compatible with the human element, recognising that while crashes might occur, the total system can be designed to minimise harm (Tingvall, 1995; Ydenius, 2010). This shared responsibility for better design is a key element of the Safe System approach.

In a sustainably safe road traffic system, infrastructure design inherently and drastically reduces crash risk. Should a crash occur, the process that determines crash severity is conditioned in such a way that severe injury is almost excluded.

Towards sustainably safe road traffic, Koornstra et al., (1992).

The Safe System approach:

Source: Bliss and Breen, 2012; OECD, (2008).

In-depth discussion of the Safe System approach, its scientific basis and scope is set out in Safe System Approach. An introduction to steps to implementing Safe System projects in low-income countries are set out in Institutional Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools and discussed more fully in Safe System Approach and Targets and Strategic Plans.

Source: Observatoire National Interministériel de Sécurité Routière (2004); FIA Foundation (2006).

Managing road safety requires institutional leadership, cooperation and delivery capacity within government agencies, as well as with their industry, business sector and civil society partnerships over a sustained period. Road safety leadership and capacity at the jurisdictional level cannot be outsourced since the issues involved go to the core of government decision-making. Careful leadership and effective governance is essential to ensure that competing interests will not obscure this shared responsibility (GRSF, 2009; SSATP, 2014).”

The World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention (Peden et al., 2004) highlights the fundamental role of the lead agency for road safety. Its priority recommendation to countries is to establish leadership arrangements and guidance based on successful practice. Experience has demonstrated the need for the agency to be a governmental body and to be publicly accountable for its performance. Without this leadership to organise the actions of all agencies and stakeholders, experience shows that even the best strategies and plans will not be implemented.

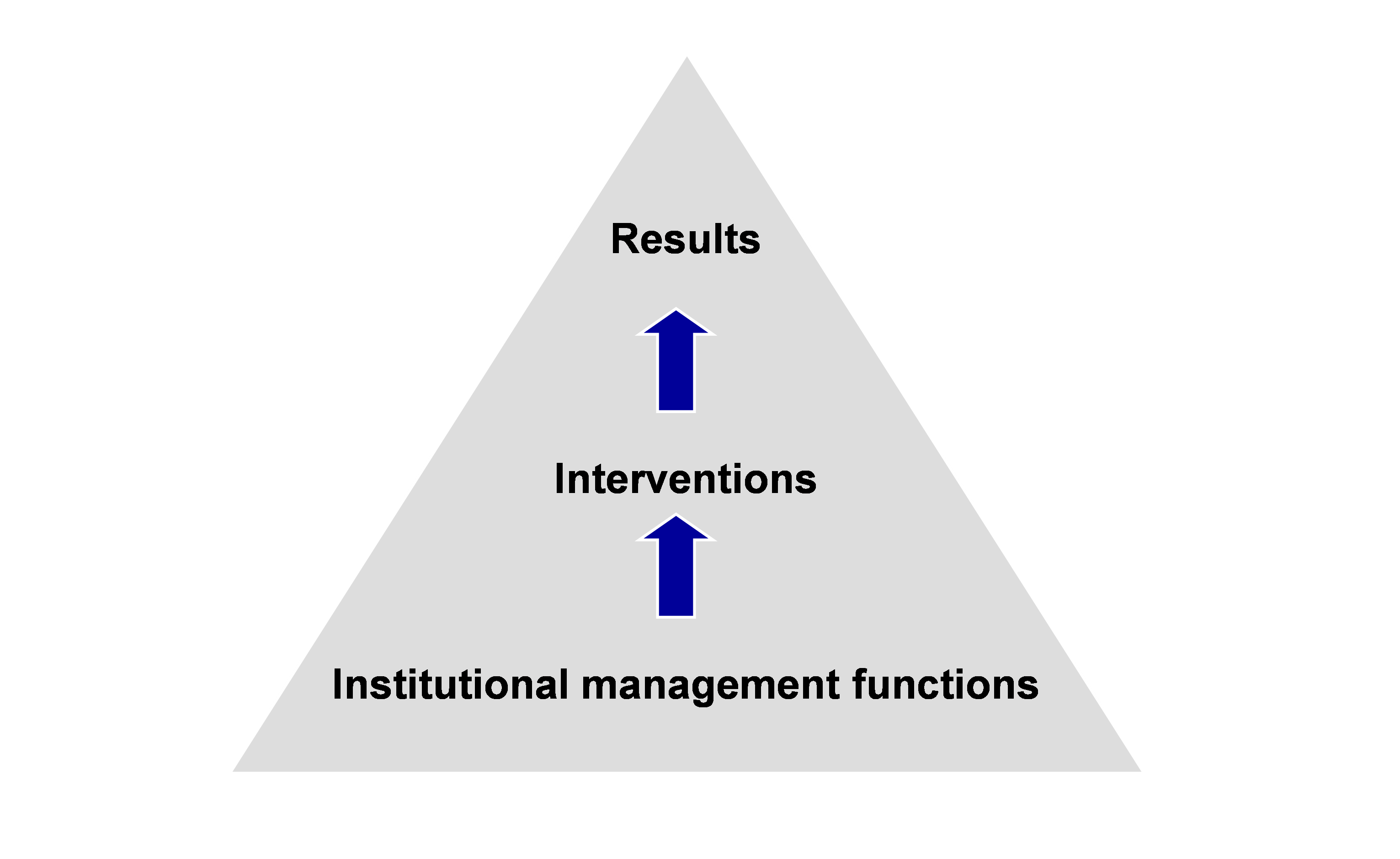

Successful road safety management is a systematic process. This has been defined and effective practice has been translated into working management system models for jurisdictions and organisations to provide tools to help address the Decade’s goals (GRSF, 2009; GRSF, 2013 OECD, 2008; ISO, 2012). As illustrated in Figure 2.3, key institutional management functions produce effective, system-wide interventions designed to produce road safety results for the interim and the long-term. See Safety Management System for a further discussion of country and organisational road safety management system frameworks.

Figure 2.3 Road safety management is a systematic process - Source: GRSF (2009) (building on frameworks of LTSA, 2000; Wegman, 2001; Koornstra et al., 2002; Bliss, 2004).

The key challenge for LMICs and international development is how to successfully implement the Global Plan's recommendations where road safety management capacity is weak. The critical issues for success are:

Sources: Bliss & Breen, 2012

Road safety management capacity reviews conducted for the Global Road Safety Facility since 2006 indicate that a clearly defined results focus is often absent in LMICs.

Coordination arrangements should be effective and supporting legislation complete. Funding needs to be sufficient and well targeted, promotional efforts broadly directed, monitoring and evaluation systems developed and knowledge transfer unlimited. Where national targets and plans have been created, adequate capacity to implement them is needed to make sure they are effective (GRSF, 2006-2012). Sustained investments will be needed in governance and institutions, infrastructure, vehicle fleets, and related investments in the health and wellbeing of citizens to address their vulnerability to risks of death and injury.

Meeting the management challenges of the Decade of Action for Road Safety will require these critical success factors to be addressed, if its ambitious goal is to be achieved (Bliss & Breen, 2012).

Based on reviews of successful as well as unsuccessful practice, the World Bank’s Global Road Safety Facility has produced a country investment model in road safety management guidelines that is designed to assist LMICs and development aid agencies in addressing the issues outlined above (GRSF 2009, 2013). These guidelines outline a practical approach designed with tools that are described further in Safety Management System. Specific guidance on steps to be taken by roads authorities in relation to the safe planning, design, operation and use of the road network is outlined in Part Planning, Design & Operation.

African Union (2011), African Road Safety Action Plan 2011-2010, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA).

African Union (2022), Consultative workshop for road safety: develop and implement national road safety frameworks for the decade 2021-2030. 30 November 2022, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) - https://irfnet.ch/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CN-AGENDA-CONTINENTAL-CONSU...

Allsop RE (2002), Safer Cities: Challenges and Opportunities, Best In Europe Conference, European Transport Safety Council, Brussels.

Bliss T (2004), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, Transport Note No. TN-1, World Bank, Washington DC.

Bliss T & Breen J (2012), Meeting the management challenges of the Decade of Action for Road Safety, IATSS Research 35 (2012) 48–55

Commission for Global Road Safety (2006, 2008, 2011), Make Roads Safe reports A New Priority for Sustainable Development, A Decade of Action for Road Safety, Time For Action, London

EC (2011a). White Paper: Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area – Towards a competitive and resource efficient transport system, COM(2011) 144 final, European Commission (Brussels, 28.3.2011

EC (2011b). Towards a European road safety area, Policy orientations on road safety, 2011-2020, European Commission (2011) Brussels.

EC (2020). EU road safety policy framework 2021-2030 - Next steps towards 'Vision Zero'. European Commission (2020) Brussels.

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) (2007), Transport and tourism issues: improving road safety on the Asian Highway, Committee on Managing Globalization, UN, Bangkok.

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) (2015), ESCAP Road Safety Goals, Targets and Indicators for the Decade of Action, 2011-2020, http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/ESCAPRegionaRoadSafetyGoals_T...

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) (2020), Regional Plan of Action for Asia and the Pacific for the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, 3rd Annual Meeting: Asia Pacific Road Safety Observatory - https://events.development.asia/system/files/materials/2022/10/202210-re...

European Transport Safety Council (2011), 2010 Road Safety Target Outcome: 100,000 fewer deaths since 2001, 5th Road Safety PIN Report, European Transport Safety Council, Brussels

European Transport Safety Council (2017), Ranking EU Progress On Road Safety: 11th Road Safety Performance Index Report, European Transport Safety Council, Brussels

Global Road Safety Facility & World Bank (2006–2012). Unpublished country road safety management reviews in low and middle-income countries, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2009), World Bank, Bliss T & Breen J. Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, World Bank Global Road Safety Facility, Washington DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2013), Bliss T & Breen J , Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, World Bank, Washington DC.

Government Offices of Sweden (2020), Stockholm Declaration - Third Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety: Achieving Global Goals 2030 - https://www.roadsafetysweden.com/about-the-conference/stockholm-declarat...

Guria J (2009), Required Expenditure: Road Safety Improvement in Low and Middle-Income Countries. Addendum: Revised Estimates of Fatalities and Serious Injuries and Related Costs. Report to the World Bank Global Road Safety Facility, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research, Wellington.

Haddon JR W (1968), The changing approach to the epidemiology, prevention, and amelioration of trauma: the transition to approaches etiologically rather than descriptively. American Journal of Public Health, 58:1431–1438. 33. Henderson M. Science and Society.

Koornstra M, Lynam D, Nilsson G, Noordzij P, Pettersson HE, Wegman F & Wouters P (2002), SUNflower: a comparative study of the development of road safety in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. SWOV, Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam.

Koornstra MJ, Mathijssen MPM, Mulder, JAG, Roszbach R & Wegman FCM (1992), Naar een duurzaam veilig wegverkeer; Nationale Verkeersveiligheidsverkenning voor de jaren 1990/2010. [Towards sustainably safe road traffic; National road safety outlook for 1990/2010]. (In Dutch). SWOV, Leidschendam.

Land Transport Safety Authority (LTSA) (2000), Road Safety Strategy 2010, A Consultation Document, National Road Safety Committee, Land Transport Safety Authority, Wellington.

Multilateral Development Banks (2009), Media Release A Shared Approach to Road Safety Management. Joint Statement by the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank and the World Bank, World Bank, Washington DC.

Multilateral Development Banks (2011), Media Release Multilateral Development Bank Road Safety Initiative, World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank, Washington DC.

Multilateral Development Banks (2012), Joint Statement to the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development by the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, CAF-Development Bank of Latin America, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, Inter-American Development Bank, Islamic Development Bank, and World Bank June 2012, Washington DC

Observatoire National InterministerieL de Securite Routiere (2004), Les accidents corporels de la circulation routière, les résultats de décembre et le bilan de l’année 2003, Paris.

OECD (1994), Targeted Road Safety Programmes, OECD, Paris.

OECD (2008), Towards Zero: Achieving Ambitious Road Safety Targets through a Safe System Approach. OECD, Paris.

Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, Mohan D, Hyder A, Jarawan E & Mathers C eds. (2004), World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, World Health Organization and World Bank (Washington), Geneva.

PIARC (2012), Comparison of National Road Safety Policies and Plans, PIARC Technical Committee C.2 Safer Road Operations, PIARC, Paris.

SSATP (2014), Managing road safety in Africa: a framework for national lead agencies, http://www.ssatp.org/en/publication/managing-road-safety-africa-framework-national-lead-agencies.

Swedish Road Administration (2019), Saving Lives Beyond 2020: The next steps. Recommendations of the Academic Expert Group for the 3rd Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety. Sweden

Tingvall C (1995), The Zero Vision. In: Van Holst, H., Nygren, A., Thord, R., eds Transportation, traffic safety and health: the new mobility. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1995:35–57.

Tingvall C & Haworth N (1999), Vision Zero - An ethical approach to safety and mobility, Paper presented to the 6th ITE International Conference Road Safety & Traffic Enforcement: Beyond 2000, Melbourne, 6–7 September 1999.

Trinca G, Johnston I, Campbell B, Haight F, Knight P, Mackay M, Mclean J, & E Petrucelli (1988), Reducing Traffic Injury the Global Challenge, Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

United Nations (2004–2010), General Assembly Resolutions 57/309, 58/9, 58/289, 60/5, 62/244 and 64/255 (Improving global road safety) and World Health Assembly Resolution WHA 57.10 (Road safety and health), Geneva.

Wegman F & Elsenaar P (1997), Sustainable solutions to improve road safety in the Netherlands. Leidschendam, SWOV, Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam.