This chapter outlines the requirements for effective road safety performance and critical success factors for road safety work.

After a thorough analysis of the country’s road safety management system and the analysis of the major risk factors, it is advisable to develop action plans with defined targets at the country level and performance measures. To determine the success of a program, or the implementation of intervention, a review of performance outcomes is needed. Because not all countries are at the same performance levels, it is often advisable to start with demonstration or pilot projects. This is particularly true for LMIC, who would benefit from the learning and building of road safety expertise through these types fo projects.

Once a country recognises that it can no longer accept the level of death and serious injury occurring on its road network, the common first response is to adopt a target performance level with a supporting road safety strategy and plan (either a programme or a group of projects) to achieve that performance. The approaches to target setting, investment strategy and plan development of HICs are usually more developed and build upon a more established road safety programme than is feasible for most LMICs at the beginning of their road safety work. This is due primarily to the differences in road safety capacity available to HICs in comparison to LMICs. Another reason is the absence of reliable crash data for LICs. Investment strategies and plans with agreed targets need not only to be developed but also successfully implemented. This is a substantial challenge.

It is useful to consider goals or targets being developed for three timeframes — there are long-term goals, medium- and short-term targets. The setting of short and medium-term targets should always be considered as milestones on the journey to achieving the ultimate target of eliminating death and serious injury. Adoption of this long-term goal will shape actions planned and taken in the interim. The setting of quantified targets for these timeframes is discussed in Setting Targets. Within any timeframe, targets can be set for final outcomes (the usual measure), for intermediate outcomes and for institutional outputs as defined in The Road Safety Management System. These options are discussed further in Performance Indicators

The underlying objective for LMICs will be the development of capacity to manage road safety, through ‘learning by doing’. An important first step is identification of weaknesses within the road safety system (both for management and for risks on the network). This should be followed by adoption of a demonstration project – across the sectors – as an establishment investment phase to build technical and management knowledge. Adequate government commitment and funding will be critical.

This first step will enable informed later stage targets (for the medium and long-term timeframes) and strategies/actions (for the associated growth and consolidation investment phases) to be devised and implemented successfully, building – in the case of LMICs – on the roll-out across the country of the interventions piloted in the demonstration corridor, the implementation of key policy reviews carried out as part of the demonstration project, and the conduct of further reviews.

Funding and implementing a demonstration project (a multi-sectoral treatment of a corridor or urban area plus some key policy review activity) is the strongly recommended means to develop capability in whole-of-government road safety management for LMICs. It should be the initial action taken, following a road safety management capacity review.

For LMICs, a commitment to improving road safety outcomes may lead to an aspirational ‘top down’ target being adopted for the short-term (e.g. next five years) with recognition that delivery of that initial target will be most challenging. However, the prime focus must be on a demonstration project or projects.

To achieve good performance a strong linkage between road safety agencies and elected members and Ministers in a country is essential. Political commitment is required to lead a country’s efforts in addressing road safety and to contend institutional management functions.

A coordination framework that links road safety senior managers through executive management, across relevant sectors, to a group of ministers meeting regularly – which makes operational decisions at lower levels and formulates policy recommendations for, and reports on strategy performance to ministers – reflects the necessary systematic view of road transport operation and its professional and political challenges. Provision for public inquiry at parliamentary level and broad consultation arrangements with stakeholders, including special interest groups, are recommended.

Model Jurisdictions: Victoria, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Western Australia, Sweden, The Netherlands.

Source: PIARC (2012).

Success in road safety work will not come overnight. The need to develop management capacity and implementation of interventions needs time. Bliss and Breen (2012) indicate that achieving results will require long-term political will that is translated into road safety investments that are targeted across a range of sectors and in governance and institutions, infrastructure, vehicle fleets, licensing standards, safety behaviours and the health system. Adequate lead time for the development of organisational and staff capability is needed.

Critical success factors (for HICs and LMICs) include:

A guide to assist nations in Africa to improve their road safety capacity in order to develop a national strategic road safety action plan is described in the case study below. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) also highlights the need to build capacity.

A regular assessment of a country’s road safety management system is appropriate to consider the achieved results, the scope and quality of applied interventions, and the efficiency of institutional management capacity. Results will reflect the interventions introduced and the effectiveness of that set of interventions, as determined by the extent of critical supporting systems in place. This will include the commitment to funding; the extent of relevant legislation; and the level of deterrence in place, including enforcement and justice system support.

Source: PIARC (2012).

Key questions that need to be considered are:

Identifying Existing Network-level Crash Risks

Capacity to identify network-level crash risks is critically important. Countries face a variety of road safety challenges on their networks. HICs have high light passenger vehicle motorisation rates, while LMICs usually experience high two-wheeler motorisation rates, high roadside pedestrian volumes, and high proportions of heavy vehicles (trucks and buses) in the vehicle fleet.

Issues influencing comparative crash risks on networks in different countries include:

the levels of safe infrastructure provision | the mix of vehicle types using the network | the controls on drivers and vehicles entering and remaining on the network |

the safety levels of the vehicle fleet | the levels of road user compliance with the laws and road rules (respect for the rule of law) | the emergency medical management of crash victims |

Understanding the relationships between road safety performance and road safety conditions is a critical requirement for assessing underlying crash risk on the road network and in taking action to reduce the risks. Relevant aspects could be

An understanding of the scale of existing problems in a country requires availability of relevant data. A lack of data makes it difficult to have a consistent evidence-based approach to identify problems and implement specific countermeasures. Furthermore, good data systems are essential to measure the outcomes of implemented interventions. The value of extensive and accurate data being available has been demonstrated in Analysis and Use of Data to Improve Safety.

Examples for the assessment of relationships between road safety performance and road safety considerations are two European studies – SUNflower and SUNflower +6 – that provided insights into this relationship in various European countries (see Box 6.2).

The SUNflower study covered Sweden, UK and Netherlands. For these countries, relationships for safety performance and underlying conditions were assessed, e.g.

The assessment lead to factors that may have contributed to differences between road users or road types and between the countries. Many of the report recommendations have been implemented in the three countries, with positive results achieved.

The SUNflower +6 study additionally covered the Central European Countries Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, and the South-European Countries Greece, Portugal and Spain.

Development of road safety in the three Central European countries varied considerably. Results reflected differences in national road safety management and enforcement strategies. In the South-European countries, vertical coordination of safety activities from central and regional to the local level was not well-developed. For some countries the identified changes were related to political changes (e.g. Portugal, Hungary, and the Czech Republic). Generally, an increase in motorized traffic resulted in a growing number of casualties. These growing numbers lead to increased attention on road safety, leading to new road safety policies and organizational measures and safety measures in the countries analyzed.

Source: Koornstra et. al., 2002; SWOV, 2005

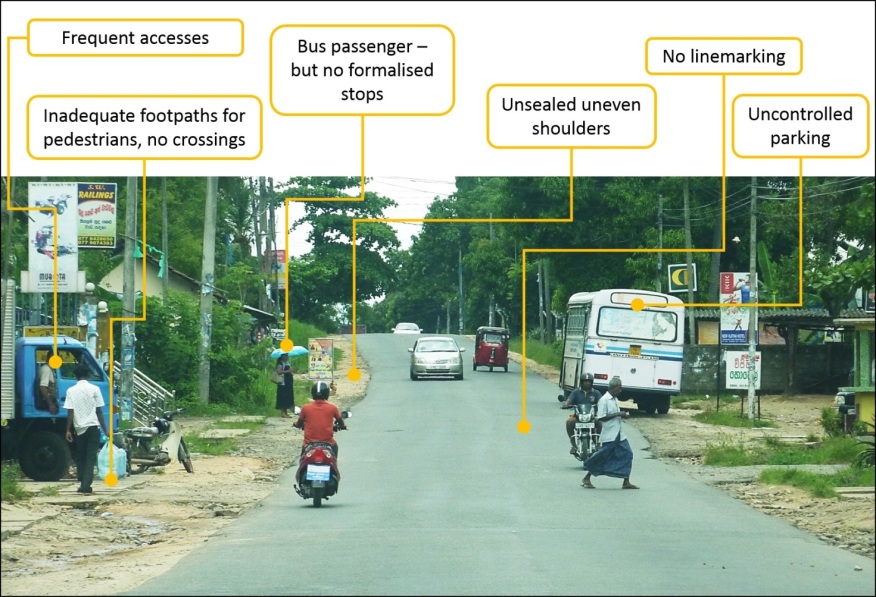

Indications of the challenges faced in understanding network-level crash risks as illustrated in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 Assessing risk on the network – major rural highways (Sri Lanka) - Source: Eric Howard.

This is just one example demonstrating the inherently unsafe condition of infrastructural conditions. In this case, the unrestricted access to the road from the roadside, and the overall poor level of management of road safety on this section of the road network poses risks. It is a situation which occurs in many countries across the world.

Target-setting can be based on the estimated outcomes of agreed action plans. Alternatively (and most commonly) targets can simply be aspirational in nature. Establishing a road safety target is a major opportunity to involve and inform the community about the road safety risks which exist in the community, the measures available to reduce the risks and to actively and openly seek the support for improved performance. There are two possibilities for target-setting – a top down declaration or a bottom up approach. A mix of these approaches is possible as well.

Top down target-setting, such as applying the Decade of Action 50% fatality reduction target for the period from 2011 to 2020 (see Typical Numerical Targets Adopted below), is much more likely to be applied in LMICs, as there is often little other evidence-based information on which to start their road safety journey. However, this aspirational approach can often lead to disappointing short-term and medium-term results.

Bottom-up target setting is based upon a negotiated set of strategic actions with a calculated (estimated) impact on fatalities and (serious) injuries. Prerequisite for this approach is good crash data, an understanding of the safety issues, knowledge of potential solutions and adequate resources. Thus targets that are more specific can be developed. Before target setting linkages between the administrative and the political level are often useful for discussion and resolution of potential implementation issues (often beyond transport impacts) that could otherwise block initiatives.

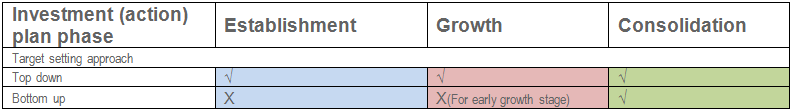

Whether the top down or bottom up approach is used to produce a target, this knowledge and experience will back strategy and action plan development and implementation. Either approach is capable of supporting improved road safety performance. However, until sufficient capacity to manage road safety is in place in a country, it is unlikely that a bottom up approach will be feasible. For this reason, Table 6.1 indicates that for the ‘establishment’ and early ‘growth’ investment phases a top down approach to target setting is likely to be the only feasible option for LMICs.

Table 6.3: Feasible target setting options

Some issues are relevant for target setting in most cases:

While LMICs could usefully base any short-term target they adopt on the five to ten year targets currently being adopted by good practice countries, there are major shortcomings in doing so:

Regional/state and local plans and targets should reflect the adopted national approach, with variations for local circumstance and intent. In this way, a more consistent understanding by the community, road safety practitioners, and politicians at various levels of government can be established. However, target-setting at the local level (as distinct from the regional/state level) is likely to be problematic as the data, resources and level of expertise are generally not readily available. Therefore, national or state targets are often adopted, that is why national plans should provide sufficient flexibility for local preferences and priorities to be identified and expressed in local plans.

Case Studies – Target-setting

Contained below are a number of case studies on target setting:

A bottom up approach to interim target-setting was followed in the state of Western Australia

Top down or aspirational target-setting is the most widely used method – and it is the only feasible approach which can be used in the establishment phase. It can also be used effectively for the growth and consolidation phases. For example, Sweden operates a mix of top down and bottom up approaches to interim road safety target-setting.

Typical Numerical Targets Adopted – Examples

Road safety targets need to be quantitative and measurable so that the level of aspiration is clear, the extent to which the target has been achieved can be determined, and if it has not been achieved, then the extent to which the result is short of the target can be measured.

Quantified road safety targets have been set in a number of regions (see Key Developments in Road Safety,) and countries in recent decades, including Finland, France, The Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the United States.

Example Indonesia: targets and policy actions expressed in the National Road Safety Master Plan 2011-2035 (Republic of Indonesia) are:

In addition to final outcome targets for overall fatalities and serious injuries being defined in a strategy, outcome targets can be set for different at-risk road user groups and for various risk categories under the Safe System pillars.

For example, the current New Zealand Safer Journeys 2010–2020 Strategy (Ministry of Transport, 2010) targets a 40% reduction in the fatality rate of young people and a 20% reduction in fatalities resulting from crashes involving drug or alcohol impaired drivers, as shown in Table 6.2.

| Target focus | Target reduction | Target focus | Target reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

Increase the safety of young drivers | Reduce the road fatality rate of young people from 21 per 100 000 population to a rate similar to that of young Australians of 13 per 100 000 | Achieve safer walking and cycling | Achieve a reduction in the crash risk for pedestrians and particularly cyclists, while at the same time encouraging an increase in use of these modes through safer road infrastructure |

Reduce alcohol/drug impaired driving | Reduce the level of fatalities caused by drink and/or drugged driving, currently 28 deaths per one million population, to a rate similar to that in Australia of 22 deaths per one million population | Improve the safety of heavy vehicles | Reduce the number of serious crashes involving heavy vehicles |

Achieve safer roads and roadsides | Significantly reduce the crash risk on New Zealand’s high-risk routes | Reduce the impact of fatigue and address distraction | Make management of driver distraction and fatigue a habitual part of what it is to be a safe and competent driver |

Achieve safer speeds | Significantly reduce the impact of speed on crashes by reducing the number of crashes attributed to speeding and driving too fast for the conditions | Reduce the impact of high risk drivers | Reduce the number of repeat alcohol and speed offenders and incidents of illegal street racing |

Increase the safety of motorcycling | Reduce the road fatality rate of motorcycle and moped riders from 12 per 100 000 population to a rate similar to that of the best performing Australian state, Victoria, which is 8 per 100 000 | Increase the level of restraint use | Achieve a correct use and fitting rate of 90% for child restraints and make the use of booster seats the norm for children aged 5 to 10 |

Improve the safety of the light vehicle fleet | Have more new vehicles enter the country with the latest safety features. The average age of the New Zealand light vehicle fleet will also be reduced from over 12 years old to a level similar to that of Australia, which is 10 years | Increase the safety of older New Zealanders | Reduce the road fatality rate of older New Zealanders from 15 per 100 000 population to a rate similar to that of older Australians of 11 per 100 000 |

Final outcome, intermediate outcome or output targets can also be devised at an organisational (road safety agency) level, compared to an overall target for final outcomes across the country – which are to be achieved as a consequence of all agency contributions.

It is most useful for all organisations to have their own strategic plan, actions and targets, based on the jurisdiction’s overall strategy. The agency strategy should indicate, in as measurable a manner as possible, how and what they intend to achieve with their own activities to meet their obligations as part of the overall country target.

Both strategies and actions are investment plans. However, Austroads (2013) notes that there is a considerable difference between countries as to what is included in a strategy document and what is included in action plans. It notes that one key point of difference is the level of detail on specific measures. Some include greater detail within the strategy, some leave detail to the action plans, while others provide detail for the initial period of the strategy (e.g. the first two years), but rely on action plans (reviewed perhaps every two years) to supply detail for later stages of the strategy. It concludes that there is no answer as to which is the best approach on this issue. The important point is that the strategy should allow enough flexibility to address any specific problems that arise as the strategy unfolds (for instance, in light of new information on potential problem groups), changes in the political environment (including changes in funding or priorities), or with the emergence of new techniques with which to address risk.

Investment strategies and actions need to be adopted to support improved road safety performance and the achievement of targets – in the short-term (one to three years), the medium-term (three to ten years) as well as in the long-term (beyond ten years). For LMICs, steady progress through demonstration projects is the recommended option for the short-term, with or without an aspirational (notional) short-term target.

For both LMICs and HICs, thoughtful investment plans and strategies will be essential to achieve steady progress towards medium-term targets and eventually to move further towards the ultimate long-term goal (see The Road Safety Management System). An understanding of the relationship between investment phases and strategy timeframes is necessary.

Figure 6.3 The phases of investment strategy: World Bank Guidelines, 2009 Source: Adapted from Mulder and Wegman (1999).

The establishment (short-term timeframe) phase of road safety investment planning focuses on building core capacity to enable effective targeted road safety performance to begin and grow. The two key purposes of activity in this phase should be:

Tasks to be accomplished in this phase may include development and implementation of necessary data systems, tools and guidelines and a strengthened legislation to be in place in time to support later implementation phases.

In the growth (medium-term timeframe) investment phase, key priorities are:

In the consolidation (long-term) investment phase, key priorities are

As stated above, action plans and investment plans can deal with different timeframes (short-term, medium-term, long-term). However, a definition of some aspects is essential, as they are important for the success of the plans in any timescale:

The challenge in LMICs is to achieve the preconditions necessary to deliver the planned outcomes. This usually requires a number of years of effort. Road safety improvement is a continuous process requiring ongoing commitment.

For all countries, in the establishment phase, there are known interventions, which if implemented effectively, will deliver results (see Intervention Selection and Prioritisation). These interventions include:

These recommended measures are applicable to all countries. However, there are further measures which would be relevant in targeting improved safety in LMICs. These measures include:

Apart from such interventions, accompanying tasks may be necessary to support road safety performance, especially in LMICs. In LMICs, demonstration projects and other means, including ongoing strengthening of existing road safety activities and the development of digital data systems for licensing and offence records (and their linkage) will be a challenging, but rewarding process. Improvements to public sector governance and the implementation of the supportive, enabling systems necessary to underpin good public policy and good road safety performance, will take considerable focused effort over a number of years.

These are substantial challenges. This is not to discourage immediate action, but there needs to be a realistic sense of what can be achieved in the short-term. This will depend heavily upon:

It is also vital that actions which increase road crash risks are not taken, even if the outcome is unintended. Box 6.5 details the unanticipated impact of resurfacing of roads leading to higher travel speeds and therefore increased fatalities in the former East Germany before remediation measures were taken.

An early action reflected the lack of available knowledge. A programme of new asphalt resurfacing of existing roads without corresponding safety mitigation measures resulted in increased speeds and greater numbers of fatalities. Time was required to identify appropriate road safety actions. Within a few years road safety success was eventually achieved, with a reduction of 72% in severe accidents and 81% in fatalities within 20 years in a sustainable way.

Source: Wenk & Vollpracht (2013).

For the growth and consolidation phases of investment, development of comprehensive strategies and action plans will be necessary and there will be capacity available by then to build meaningful proposals which can be fully assessed for their likely contribution to proposed targets. In the later part of the growth phase and beyond, the estimated aggregate impact of implementable actions can be utilised to provide a target (see Setting Targets).

In this phase developed capacity data, tools and knowledge have to be available to

In HICs and LMICs there will be many potential interventions which can be applied in the growth phase and beyond. Later chapters address road safety engineering interventions in detail (see Intervention Selection and Prioritisation), and other interventions (such as improved road user behaviour through legislation, enforcement, and licensing; improved vehicle standards; and improved post-crash care) are also important.

Interventions (i.e. countermeasures) to address the identified risks in the growth and consolidation investment phases can be developed based on evidence from demonstration projects and other jurisdictions, as well as from research. The Austroads Guide to Road Safety Part 2 (2013) provides a conceptual framework for countermeasure selection, based on the Safe System approach, and sets out steps for:

After setting targets, developing action and investment plans and the implementation of interventions it is of utmost importance to review the performance. Intermediate outcomes (performance indicators) (OECD, 2008) are valuable in predicting final outcomes (see also The Road Safety Management System and Effective Management and Use of Safety Data).

A number of possible intermediate outcome measures are specified in those chapters, for example, seatbelt wearing rates or speed monitoring. For LMICs e.g. truck rear lighting operational rates, wrong-way vehicle travel rates, proportion of length of high pedestrian areas with footpaths, rate of provision of raised speed reduction devices with highly visible advanced signage at pedestrian crossings on arterial roads in urban areas, and more can be mentioned.

One option (Austroads, 2013) to link these measures to adopted targets is to develop an ‘outcome management’ framework which directly links the outputs from the strategy (i.e. what will be done) with outcomes (i.e. what is to be achieved). This is a useful approach which focuses attention on key outcomes, encourages modelling of effectiveness of outputs on final and intermediate outcomes achieved, and assists in the monitoring process.

Establishing road safety targets and investment strategies and plans is complex, requiring

As recommended in Institutional Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools, the first step for LMICs in establishing their road safety activity (their establishment investment phase) will be to prepare demonstration projects rather than embark on ambitious national road safety plans and aspirational targets which are more appropriate for the growth investment phase in the medium-term. Box 6.6 outlines the high-level objectives of Safe System demonstration projects.

Source: GRSF(2013).

It is important to note that a demonstration project must be carefully adapted to each country. Even though the project will generate expertise, it is vitally important to prepare an ongoing programme for future actions, based on each country’s capacity.

For HICs, demonstration projects across road safety agencies that trial innovative treatments can also be an effective way to prepare for wider roll-out. It can strengthen institutional leadership and capacity, including knowledge and delivery partnerships. Projects of this nature provide a focused opportunity; for example, the chance to trial and embed Safe System approaches within new strategies and within the practices of the road safety agencies.

Road Safety demonstration projects could be multi-sectoral activities on selected road corridors or in specific urban areas, and they could also include selected jurisdiction-wide road safety policy reviews. All require coordinated action, by and across the road safety agencies, but with projects at a smaller and more manageable scale than for the complete country or for all potential policy reviews. Note that the term ‘demonstration project’ is sometimes used to describe a small-scale trial of a specific treatment type (e.g. a new innovative treatment). Advice on these and other lower cost approaches is provided elsewhere in this manual (see from Infrastructure Safety Management: Policies, Standards, Guidelines and Tools).

Capacity needs to be progressively developed, with coordination and decision-making mechanisms agreed to between the road safety agencies, and then successfully introduced and experienced on a day-to-day basis. Links up to decision-making at the political level (between Ministers) need to be achieved. In this environment of unavoidably slower development of understanding and capacity, most benefit will be derived by ‘learning by doing’. The key deliverable would be improved capacity of the country’s road safety agencies to deliver road safety improvement. It would also provide a clear message to the community that improved performance is achievable.

Coordinated on-road corridor treatments of demonstration projects can be:

Separate from those corridor actions policy development components of demonstration projects (separate from the corridor actions) will usually include some of the following:

The resourcing, guidance and persistence needed to achieve even small changes in approach by the agencies will be substantial. Experience has shown that the level of effort required for this is consistently under estimated and under-resourced. The measurement (both baseline and ongoing) and monitoring of intermediate outcome performance is an essential component of demonstration project activity and is important for the later phases of broader road safety activity.

While detailed digital crash record databases may not be in place, the level of overall fatalities can be collated from local police records and hospital records for the demonstration project corridor activity, and usually (with effort) for a larger area. The country would then be in a position to assemble the evidence base to assess demonstration project benefits and this would support a broad roll-out programme for the subsequent medium term or growth phase.

Detailed project objectives and project components for a road safety demonstration project, drawn from recommendations for the establishment phase arising from a typical recent World Bank road safety management capacity review, are set out in Table 6.3 and Table 6.4.

| 1 | Strengthen road safety management capacity in Country A to deliver a demonstration project. Establish road safety decision-making arrangements at executive and working group level of the key agencies, and consultation arrangements with stakeholder groups/experts |

|---|---|

| 2 | Designate a lead agency to conduct the demonstration project and specify its formal objectives, functions and resourcing requirements. This will include a small road safety cell to provide advice and secretariat services to the coordinated decision-making of project partners. |

| 3 | Develop and implement interventions by the sectors in a selected corridor. Monitor and measure changes in road safety performance. |

| 4 | Identify and conduct selected policy reviews to address key road safety priorities. Make recommendations to improve road safety results. |

| 5 | Accelerate road safety knowledge transfer to strategic partners. |

These five objectives are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. The aim is to create a joint project which encourages agencies to work together constructively to: deliver (and then evaluate) a set of well-targeted, good practice interventions across the sectors in identified higher-risk corridor(s); conduct further policy reviews; and accelerate road safety knowledge transfer. It is anticipated that the road safety demonstration project may typically cost around US $20 million (and at least $10 million as a minimum), have four major components and be implemented over a four year timeframe (see Table 6.4).

| Component | Typical US $m. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A resourced project executive committee to lead and manage components 2,3 and 4 | |

| 2 | Interventions in high-risk, high-volume demonstration corridors (urban and rural sections) with monitoring and evaluation systems in place. | 19.0 |

| 3 | Policy reviews of road safety priorities, e.g. from projects such as driver licensing standards; heavy vehicle safety; safe infrastructure design, operation, management standards and principles; crash investigation capability strengthening for Police; developing road safety research capability; penalty frameworks for offences | 0.4 |

| 4 | Building knowledge through technical assistance, study tours to other countries, and a fully resourced road safety group (or cell) | 0.6 |

| TOTAL | 20.0 | |

The recommended scale of demonstration projects is around this amount and timescale because minor funding is unlikely to realise benefits described earlier in this section. The substantial change in the management of road safety from individual agency ‘best efforts’ to a coordinated and well led whole-of-government management approach, which builds the skills necessary to manage a whole of country improvement, requires significant investment and leadership. Governments and funding agencies need to recognise this requirement. An example of a demonstration project is provided in the Kerala, India case study

Austroads, (2013) Guide to Road Safety Part 2: Road Safety Strategy and Evaluation, Austroads, Sydney, Australia.

Bliss T & Breen J (2012), Meeting the management challenges of the Decade of Action for Road Safety, IATSS Research 35 (2012) 48–55

Bliss T & Breen, J (2013), Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2009), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, by Bliss T & Breen J; World Bank Global Road Safety Facility, Washington DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2013), Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, by Bliss T & Breen J; World Bank, Washington, DC.

Koornstra M, Lynam D, Nilsson G, Noordzij P, Pettersson HE, Wegman F & Wouters P (2002), SUNflower: a comparative study of the development of road safety in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. SWOV, Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam.

MUARC, (2008), Development of a New Road Safety Strategy for Western Australia, 2008 – 2020, Report No. 282, Corben B, Johnston I, Vulcan P, Logan D.

Mulder, J & Wegman, F, (1999), A trail to a safer country, PIARC XXIst World Road Congress, Kuala Lumpur, SWOV, Leidschendam, Netherlands.

New Zealand Ministry of Transport, (2010), Safer Journeys 2010–2020 Strategy, New Zealand Ministry of Transport, Wellington, New Zealand.

OECD (2008), Towards Zero: Achieving Ambitious Road Safety Targets Through a Safe System Approach, OECD, Paris, France.

PIARC (2012), Comparison of National Road Safety Policies and Plans, PIARC Technical Committee C.2 Safer Road Operations, Report 2012R31EN, The World Road Association, Paris.

Republic of Indonesia, (2011) National Road Safety Master Plan 2011-2035,

Road Safety Authority, (2013), Road Safety Strategy, 2013—2020, Government of Ireland, http://www.rsa.ie/Documents/About%20Us/RSA_STRATEGY_2013-2020%20.pdf

SWOV, (2005), SUNflower+6; A comparative study of the development of road safety inthe SUNflower+6 countries: Final report, Wegman F, Eksler V, Hayes S, Lynam D, Morsink P, and Oppe S.

Wenk, S & Vollpracht, H (2013), A comprehensive approach for road safety exemplified by the State of Brandenburg 1991-2012, World Road Association (PIARC), Routes/Roads 360, 88-93.