Responsibilities of a road authority include safe road design for new roads, safety improvements of existing roads, safer outcomes from road maintenance and network operation activities. Actions need to be undertaken within the whole-of-government road safety efforts. These activities need to be conducted within a Safe System framework, a transforming safety agenda that will influence all the activities of a road authority, not just those activities traditionally considered to be the functions of a road authority’s safety division. It challenges road authorities to rethink their activities. This is a major challenge for every road authority – how to build Safe System principles and elements into all of its activities.

Case 1. In some jurisdictions, the road authority will be the lead road safety agency, particularly where the authority is also responsible for traffic management, driver licensing and vehicle registration.

Case 2. However, in many instances, the road authority will have reduced responsibilities and will not be the lead agency.

What can we do in such case? In this situation it will need to rely more heavily on the cooperation of other stakeholders to achieve the desired safety outcomes. In all cases, road authorities need to have a strong external focus to achieve gains in other Safe System elements that are outside their normal areas of operation.

Key stakeholders include:

This cooperative role requires strengthened knowledge and new skills in outreach and communication because it is necessary to work with others outside of one’s typical profession.

The focus in this chapter is on embedding the Safe System approach within the responsibilities, (planning, policies, programmes and operational activities) of the road authority in a jurisdiction, particularly the identification of necessary changes, their progressive introduction and their ongoing application. It is important to recognize change is necessary to achieve the safe system approach and it is important to consider the steps necessary to achieve this overall goal. It is also important to recognise that the level of effort may vary depending on the will of the decision makers responsible for providing resources to the effort.

STEP 1: gathering and collecting information on the existing system

The starting point should be mapping the alignment of existing functions and responsibilities of the road and other safety authorities participating in the effort to implement the Safe System principles. This will produce an understanding of the extent of alteration required to align the activities of all authorities. This adjustment will have to be substantial and will need to take place progressively as understanding and experience with application of principles increases.

STEP 2: consultation and discussion

Effective change management strategies are supported by corporate-wide processes for input, consultation and discussion. A strategic framework with clear objectives needs to be put in place and progressively strengthened with policies and guidelines as knowledge increases. All changes will need to include a continuous improvement and feedback process to refine and identify necessary adjustment to current approaches and priorities in all areas of the authority’s activity.

STEP 3: institutionalization and formalization

The new approach will need to be fully embedded in the road network management approach of the road authority and formalisation of this positioning is recommended in time. Regular assessment of the coverage and effectiveness of this ‘embedding’ activity will be needed.

FUNDING POINTS:

Relevant legislation and regulations will prescribe the functions and responsibilities of a road authority in a country. While the nature and extent of these responsibilities varies from country to country, it will usually encompass planning and construction for major new road projects, safety, asset management, traffic management, road maintenance, and of way and abutting development regulation, to varying degrees. The responsibility for the setting of speed limits on all roads, or perhaps just for national or state roads, while issuing guidance for speed limits and design standards on local roads is likely to rest with national or state road authorities. However, this is less likely to be the situation in a number of LMICs.

As a basic starting point, the legal obligations of a road authority for safe operation of its network will require risk management systems and procedures to be in place that:

As an example, road authorities may have a duty of care to identify, assess and prioritise risks, and take reasonable measures to address them. This obligation typically covers all road users (including pedestrians, bicyclist, and emerging mobility devices), and covers the full road reserve (i.e. including roads and roadsides).

However, countries will have varying legislative and regulatory responsibilities setting out safety requirements that are binding upon their road authorities.

A priority safety focus for road authorities will include infrastructure safety, land use and access control from land abutting road reservations and speed limit setting, the Safe System approach requires all the elements affecting safety on the network to be taken into account by the road authority when discharging its responsibilities.

This can be complicated in situations where responsibilities are divided or separated between departments. Examples of this may include the setting of speed limits, traffic management planning and the management of heavy vehicle operation. These functions may be carried out by a different department to the road authority (e.g. Department of Transport or Police). In these instances, there is the challenge of reaching agreement with other departments about consistent practice.

It is recommended wherever possible that these responsibilities be made part of a road authority’s role. If this cannot be achieved, the road authority must be given powers to be involved (with their agreement) in establishing guidelines and standards which will be applied for these responsibilities.

All of these matters are associated with safe operation and use of the network. These operational characteristics are a key determinant of the level of crash risk experienced on the network. Considerably more active coordination effort than usual will be necessary for the agencies to achieve effective safety outcomes in these ‘separated responsibility’ situations.

The road authority has an obligation to support achievement of:

Road authorities need to work with local police and provincial and local governments to explain the importance of their roles in achieving safe operation of the road network. They need to support and encourage police action in achieving compliance with speed limits, but also for seatbelt and helmet wearing, pedestrian priority on crossings, safe overtaking, observing traffic controls at intersections, safe heavy vehicle operation and minimising impaired driving.

The Road Safety Policies Team: Within a road authority exists a group of professionals with accountability for initiating road safety policy and guideline development (usually a road safety engineering team or section) and for making relevant recommendations to the senior corporate group which carries a considerable responsibility. Such a Group needs to be prepared to put forward policy positions that would reduce crash risk on the network, while recognising that this will impact upon traditional approaches.

The Road Safety Engineering Team: Other parts of the organisation (maintenance, design, asset management, traffic management) will need to be consulted and engaged in order to assist the change in thinking necessary for gaining corporate support for changing their activities. This is a substantial task – shifting the traditional approach taken to building and maintenance of roads – in order to win the understanding and acceptance of the need for retrofitting work on road networks to change crash risk profiles over time. A road safety engineering team within a road authority should be capable of operating as a centre of expertise to support the roll-out of road safety knowledge and programmes across the regions and, as appropriate, within head office functions.

Expertise will be needed to carry out a number of key functions including:

Local governments will need support in introducing Safe System principles, and will also contribute input about how Safe System treatments can be more effectively implemented. The importance of the role of local government is illustrated by the example of Indonesia where recent data suggests that more than 70% of road crash fatalities occur on provincial and local roads and streets, not national highways.

In addition, local governments have land use planning responsibilities to control the nature of new development, access to road reserves, and prevention of illegal development. They also have roadside management responsibilities to control the unsafe effects of roadside activities. These powers often apply to national roads in LMICs.

It is often the role of local government, for example, to provide footpaths abutting new road developments or existing roads. There is a need to consider pedestrian safety issues as well as motorised road user and cyclist safety. Policies need to be devised and adopted for safe movement of pedestrians along and across roads and for potential treatments at higher-risk locations. Funding arrangements need to be resolved to ensure pedestrian facilities are in place or provided.

Simple tools to support improvement of knowledge and capacity at the provincial and local levels will be needed, as will adequate funding, although funding arrangements are usually complex and specific to each jurisdiction.

Safe System introduction is likely, over time, to lead to fundamental change in an authority’s approach and programmes. Cost-effective safety interventions and investment will become a more substantial component within new projects and maintenance and reconstruction works, and will also support improved worksite safety management. For all LMICs, understanding and identification of higher crash risk issues (e.g. through application of proactive network risk assessment programmes and blackspot analysis) will increase demand for implementation of treatments. Allocations for road safety funding within annual budgets in order to respond to these demands will increasingly emerge. Without funding commitment by government (supported by innovative safety programme business case submissions from the road authority), nothing will change.

Increased funding for safety projects will require linkage to new safety-related corporate KPIs whose measurement will enable management of effectiveness to occur. Box 7.1 illustrates an approach to introducing funding of Safe System treatments.

Road safety in Sweden is mostly funded by government and through general revenue distributed to the lead agency – now the Swedish Transport Administration (STA) – and other sectors. In 1999, funding to the lead agency was doubled with a total of SEK 8.5 billion ($US 1.25 billion) to be made available for road safety over 10 years. An increased and earmarked allocation was made to allow resources for physical road safety measures such as roads with median guardrails, safer intersections and safer road shoulders. Road safety engineering is being increasingly brought into the mainstream of infrastructure development and asset management.

Obtaining Safety Funding from other Administrations - Opportunities for obtaining targeted funding for road safety investment (e.g. infrastructure safety works, additional enforcement, public campaigns, and conferences and seminars) need to be pursued by all agencies, especially health and road authorities given the relatively high cost of infrastructure provision and implications of crash outcomes on the health system.

How to Obtain Safety Dedicated Funding - Obtaining adequate safety funding is a leading responsibility for a road authority. Revenue sources such as from the introduction of more efficient enforcement mechanisms (automated enforcement) for the collection of traffic fines and injury insurer contributions on the basis of achieving a satisfactory rate of economic return on investment through lower claims experience, warrant particular attention. In some countries such as Australia, Canada and Sweden, the injury insurers fund major advertising, research and enforcement programmes and revenue from traffic infringements (Australia and France) funds major infrastructure programmes.

The goal of The Safe System Approach is that the infrastructure and road environment support a safe outcome for all road users when they make errors, and do so by taking into account human crash thresholds.

Policies, guidelines and programmes need to be developed to ensure progressive advancement towards a network embodying Safe System principles and outcomes. The progressive adoption of Safe System goals and strategies within the operational practice of road authorities requires considerable investment in knowledge, skills, policy and guideline development, both by the road authority as an entity and by individual staff.

More road authorities are recognising the major implications that adoption of a Safe System has. The role of the road authority is to provide a safe network that will require the progressive reduction of the traditional trade-offs that have historically been made between safety on the one hand, and mobility and access on the other. Rather than trade-offs, ‘win-win’ outcomes are required and need to be planned over time.

Support for infrastructure safety investment in order to achieve non-fatal crash risk conditions across the network (the spirit of the Safe System Approach) will become the priority. This is likely to result in substantial increases in the influence of the safety-focused infrastructure compared to other road safety programmes.

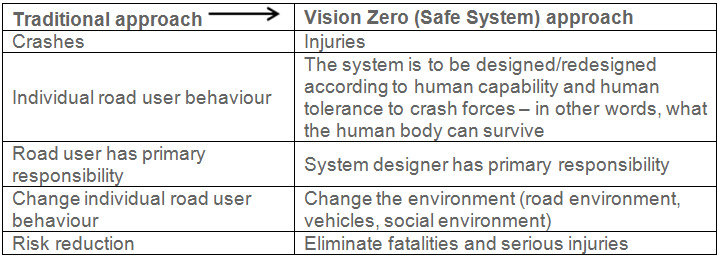

An Example: A comparison from Sweden between the Safe System/Vision Zero approach and a traditional road safety approach as presented in Table 7.1 is instructive.

Table 7.1: The Safe System paradigm shift - Source: Based on presentation: Vision Zero – a road safety policy innovation (Belin, Tillgren & Vedung, 2012).

A New Safe System Focus for Programmes and Projects

Road authorities (and all road safety agencies) have to recognise that the framework for understanding and managing crash risk has to be thoroughly rethought. Existing knowledge of the new framework and responsibilities for determining and responding to crash risk in many LMICs is inadequate.

As an illustration of authorities recognising the need to make this major adjustment, and in doing so, Slovenian road safety authorities (Zajc, 2014) express their new approach as shown in Box 7.2.

The driver was treated like a potential delinquent.

Now: The traffic system must accommodate the driver.

The driver is a victim of the traffic system because she/he has a limited capability for processing all traffic information. The system must be simple so that the driver makes less mistakes. When the driver makes mistakes the system must forgive him and reduce the consequences.

Source: Zajc (2014).

On the other hand, an indicative example of the lack of adequate understanding of crash risk and appropriate good practice responses within the activities of two road authorities is set out in Box 7.3.

Discussions as part of a road safety capacity review were held with the national road authority in a south-eastern European country in 2008 to ascertain, among other issues, why barrier linemarking on a particularly mountainous national road, with a high proportion of truck traffic, was only in place for some 50% of the length required by international overtaking sight distance standards. The response of the authority was that ‘if the full barrier linemarking were to be installed to meet the safety standards, it would mean overtaking opportunities would be very limited’. This trade-off between safety and amenity (or ‘efficiency’ as some would consider it) was not transparent . There had been no community debate about serious crash risk versus faster journey times. It is an all too common example of safety not being fully supported or being covertly traded-off for other purposes in the past.

The approach adopted in Argentina to implement a Safe System focus is explained in the following case study..

© ARRB Group

Implementing Safe System principles on major new road projects and, particularly, delivering improvement in the safety levels of the existing network over time will require, among other measures, adequate controls on roadside access and roadside activity to be put in place. Necessary powers and government actions to regulate abutting land use development and roadside activities on existing roads for this purpose will be required.

Road authorities and local Governments: Processes to assess the safety impact of any proposed land use development need to be established between the road authority and local governments. Potential safety issues need to be identified, and a range of responses developed as potential development conditions in order to minimise future harm. These processes need to be given authority within land use planning and local government legislation.

Favouring Legislation: Laws to support improved compliance by the public with the decisions of the road authority/local government in these matters will be required, and these need to be enforced. Consideration is required of incentives to be introduced to encourage local government to adhere to their land use planning policies. It is most important that the stakeholders understand and accept the need for legislation to control this development and that the road authority:

Box 7.4 sets out a discussion that addresses a number of highly relevant safety concerns in many LMICs for so-called linear settlements. These common situations reflect inadequate public administration powers (or their lack of application), leading to highly unsafe road environments especially for vulnerable road users.

A major factor in road fatalities in LMICs is vulnerable road users on roads abutting so-called linear settlements. Here, the lack of access control and poorly conceived investment strategies for road networks (and for the development of communities) has resulted in mixed functions with residential and business along the country’s main arterial roads, with heavy, high-speed traffic activity. These ‘coffin roads’ are well-known examples of the problems with linear settlements on busy upgraded roads and occur in many LMICs.

Vulnerable road users are not the only ones at serious risk. Poorly planned U-turn provision or inadequate physical restrictions on U-turns along LMIC highways are a major cause of serious casualty crashes, especially among the passengers of public transport mini buses (e.g. in Egypt). These U-turn gaps and permitted operations are a disaster for road safety. This is a deeply embedded characteristic of the road network in LMICs and requires action across many road authorities in achieving adequate local government development planning to support safe road -of-way management.

Measures required based on good HIC practice include:

Source: Adapted from Vollpracht (2010).

Linear settlement roads result in unsafe conditions, with pedestrians and vehicles entering and exiting the road from each (continuously) abutting property frontage. Safe System principles indicate that each property entry to a roadway functions as a minor intersection, with the possibility of -angle crashes involving vehicles entering or leaving the carriageway colliding with vehicles travelling along the road. These situations compromise efforts in many jurisdictions to devise a consistent road classification system applying along lengths of road. A further example highlighting solutions for addressing linear settlements is provided in Box 7.5.

A strategy to address these risks was proposed with two components:

1. An express road system with a 2 + 1 lane cross-section bypassing villages and towns can nearly halve the price for motorways and will be sufficient for traffic volumes up to 20,000 vehicles/day. So the main and safe arterials in Republika Srpska can be built up much earlier than the planned motorway system. They can be widened later, as soon as the traffic volume needs a second carriageway.

2. Adapt the existing main and regional roads within linear settlements to a mixed use function by traffic calming and providing safety for non-motorised users.

Source: Kostic et al. (2013)

As outlined above, unauthorised activities carried out on the roadsides, especially on heavily trafficked routes, need to be regulated and managed to minimise adverse safety impacts for road users. This is an area of considerable weakness in many LMICs, with traders and vendors occupying the road reserve, setting up goods and stalls. In urban areas, traders’ goods and itinerant vendors take over the footpaths, forcing pedestrians to use the road for walking. There is often little management of this unauthorised use by the local government authorities or the police. It is a major challenge for road authorities to obtain the attention of government and gain their support to change the situation. However, there are successful examples in LMICs of local governments negotiating relocations of street vendors to public market spaces, re-established away from the main roads to improve safety.

© ARRB Group

Adoption of an increasingly safety sensitive road classification for the network that better matches road function, speed limit, layout and design is an important aspiration. As noted above, linear urban development is a characteristic of most LMICs and tends to confound this classification approach. Planning to progress toward the long-term goal of segregation of road use functions and improvement in operating safety is important for Safe System adoption. Suitable planning can guide future road investment (for example in provision of bypass roads) and the associated safety retrofitting of existing roads for their access or distributor functions.

As indicated earlier (see Safe System : Scientific Safety Principles and their Application), the Sustainable Safety approach from the Netherlands places a heavy emphasis on a strong road classification system. Road functionality is embedded in the approach, and it is suggested that roads should have a single function, whether this be as through roads, distributor roads, or access roads. This concept has been well understood for many years, but in more recent years there has been an increased recognition that more needs to be done to ensure this distinction is made. This includes providing an appropriate classification system, allocating all roads to this, and ensuring that the design, and understanding by road users is consistent with this function. Further information is provided on this issue in The Basics: Road user Capacities and Behaviours in Designing Infrastructure to Encourage Safe Behavior, including a discussion on ‘self-explaining roads’ to support road user understanding of this functional classification.

It is a challenging and potentially lengthy process for a road authority to move from adopting Safe System principles to implementing these within a road authority’s operations. Progress will be measured in years rather than months. Moving to embed a Safe System approach is likely to involve the following:

A summary of some key issues and potential actions or processes associated with moving to embed the Safe System within a road authority’s management systems is set out in Table 7.2.

| Issue | Potential actions/processes |

|---|---|

How can a road authority commence the process of embedding the Safe System approach in its operational practice? | Role statements and accountabilities at all levels in the road authority should reflect the actions and outputs expected to deliver Safe System progress |

How to commence/continue the transition from traditional approaches to the Safe System philosophy | Ensure that there is a high degree of understanding of the benefits associated with the proactive risk minimisation approach. The Safe System principles and scientific design foundations should be clearly and consistently communicated to agency staff and stakeholders. The economic and safety benefits of adopting this approach should be demonstrated through case studies and communicated widely within the organisation |

How to implement Safe System principles in horizontal and vertical corporate communication and decision-making processes | Corporate processes need to have Safe Systems outcomes embedded in them to strengthen development of a continuously learning organisation Continuous policy development should also be informed from operational development and implementation experience. Feedback from these activities is an essential means of improving policies and guidelines to embrace and deliver Safe System outcomes |

Formalised arrangements for the new ways of managing safety on the network | Apply these policies and develop supporting systems to incorporate proactive network safety management within the planning, project development, design, operation and maintenance activities of the authority. Establish ongoing performance measurement of safety outcomes to assure the community that the level of the authority’s safety performance is improving |

Addressing community/stakeholder awareness and acceptance of implications of adopting Safe Systems principles | Develop a communication strategy with agreed key messages and mediums for dialogue with identified stakeholders. |

At the outset, any existing national road safety strategy will need to be reviewed and if necessary adjustments to the strategy made to include the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety’s Safe System basis. It is expected that many LMICs will need to review the adequacy of their processes (see Establishing Corporate Processes to Develop Policy in Embedding the Safe System in the Goals and Operational Practice of Road Authorities for guidance on this).

The leadership will also need to recognise the changed organisational responsibilities that will flow from these decisions and consider how to go about providing for these changes. The needs and the environment in which the road authority in any country is operating will influence the detail of this.

Progress will depend heavily on leadership provided by the chief executive. These are quite challenging change management tasks, winning the support and commitment of senior management within the organisation is a key first step and priority.

Training programmes, such as those outlined in Learning and Knowledge Development in Embedding the Safe System in the Goals and Operational Practice of Road Authorities will be important on an ongoing basis as improved corporate policies and network management systems are adopted by the organisation. For any road authority moving to embed Safe System practice, senior and middle management need sufficient time to learn about and understand the underlying concepts.

The internal communication processes in place to support change management also need to be reviewed if meaningful change is to be introduced over time. This would include effective communication across all levels of government and between head and regional offices.

The experience of the Swedish Road Administration in introducing Safe System (Vision Zero) thinking and moving to implement associated and substantially different infrastructure safety programmes across the organisation is instructive (see Box 7.6)

From 2000 to 2009, Sweden moved to increase the 2 + 1 barrier divided road network on the more heavily trafficked sections of the national highway network. The length of this treatment increased from 180 km in 2000 to some 2120 km in 2009. This was to address the high incidence of head-on crashes experienced on the network, due in part to the existing 13 metre wide pavements (two through lanes with wide shoulders), which encouraged a form of four-lane driver behaviour, leading to increased head-on crash risk. Sweden also began to install side barriers to address run-off-road serious crash risk and to expand programmes to install roundabouts to address serious crash risks at intersections.

The decision made at head office for barrier expansion, in particular from 2000, took some time to achieve general compliance and support by all regional managers. In fact, performance targets for regional managers (for 2 + 1 lanes with wire rope median barriers) were required in order to drive compliance with corporate policy. Some regional managers considered the policy directives for central medians and 2 + 1 lane construction to not be in accordance with traditional approaches.

Road fatalities fell from 550 to some 350 annually in that 10-year period as the roll-out proceeded, and became an acknowledged world leading set of initiatives (part of the Vision Zero implementation).

.

© ARRB Group

Box 7.7 outlines an example of a road authority, which sets out the basis for its transformation to an authority that will fully integrate Safe System thinking into its activities and the associated strategic objective it has adopted. Main Roads Western Australia (MRWA) is an informed user of the Safe System, with an understanding of, and experience with, its application. The process MRWA has adopted to guide its use of Safe System principles within its operations is comprehensive and informative for other road authorities that are in a similar advanced stage of awareness of the Safe System.

The vision:

To eliminate death and serious injury crashes on the Western Australian road network and leave a lasting legacy of a safe road system for our children, grandchildren and the community.

Strategic objective:

The MRWA road safety strategy The Road Towards Zero is aimed at bringing about changes to our road safety institutional arrangements, practices and culture as we strive to eliminate death and serious injury. In doing so it will:

The Road Towards Zero’s strategic objective reflects this focus on cultural change: To change thinking, practice and behaviour – to let staff imagine all things possible – to build, maintain and operate an inherently safe road system.

As indicated earlier, relevant legislation under which the road authority operates will influence the way that the authority proceeds to implement a Safe System approach.

Building awareness of Safe System possibilities and application will be achieved through leadership, training and knowledge development as discussed in detail in The Safe System Approach. Resourcing this awareness building is a critical step for LMICs.

Effective training and change management activities will be crucial enablers to achieving Safe System progress. New Zealand, which has a well-advanced Safe System approach has implemented sector-wide training programmes through the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) (Climo et al., 2014) as presented in Box 7.8

Safer Journeys (the NZ strategy) acknowledged the need to embed the Safe System into New Zealand’s road safety culture and to develop the capability to do so. Within four years of adopting a Safe System approach the NZTA has moved to incorporate Safe System processes within its operations.

A structured ‘culture change’ programme was embarked upon, which provided detail about what it meant in practice and what it needed to do differently. Supporting resources were developed as follows:

A range of existing policy, procedure and guideline documents, likely to have the greatest influence, were identified and a programme of updating these embarked upon.

The second Safer Journeys Action Plan (2013-15) has continued this focus with specific ‘Advance the Safe System’ tasks that include:

Source: Climo et al. (2014).

NZTA’s experience has demonstrated that culture change is not a short-term or easy task. It requires leadership from the highest level such as politicians and chief executives and perseverance, with continual repetition of simple key messages. It has also been recognised that changing the conversation in the media, away from the ‘driver blame’ culture, will be critical to success.

Effective staff development will require programmes such as New Zealand’s (above) and other more ‘entry-level’ programmes to be identified and then utilised for relevant professional development of staff, particularly within LMIC authorities. Activities such as short-term (two to four week duration) staff exchanges with other national road authorities, and seminars by local and international experts to inform and obtain input about road safety policy-related matters, should also be pursued.

A continuous change and improvement culture should be fostered, with an extended training programme for head office staff and the regions being introduced at the appropriate time. These are pivotal steps in helping to underpin safety knowledge and fostering improvement in safety performance by a road authority.

Initiatives to assist focused application of Safe System principles within road authority programmes and projects include:

Many professionals within road authorities learn about crash analysis, development of treatment options, selection of the most cost-effective option (with a focus on reducing fatal and serious injury crashes, as distinct from all crashes), and implementation, through high-risk location (blackspot) projects and programmes. On the contrary, it would be preferable for a road authority to move as soon as possible to a network-wide assessment and treatment of crash risk, high-risk location treatment projects – which are based on solid evidence of crash types and robust estimations of project costs and crash reduction benefits, followed by later evaluation – are a key learning tool for professional road safety engineers that are starting out in road infrastructure safety. Such projects, as long as they are pursued with a clear Safe System focus and basic initial understanding, are important steps for individuals along the path to broader understanding of crash risk and tools.

Examples of demonstration projects in a number of countries by all the road safety agencies, including the road authority, to improve crash risk analysis and treatment knowledge are provided in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects.

Change is always challenging and the scale of reassessment or reframing of policies and guidelines involved with fully embracing the Safe System is substantial. These are large steps for any road authority, but it is a substantial challenge when a typical LMIC authority embarks on this journey. Moving from understanding by individuals to adoption of a corporate consensus and then agreeing on the new road safety vision and how it is to be applied is a challenging process for any road authority. Processes of this type will be less developed in most LMIC road authorities but dialogue and discussion need to be encouraged as soon as possible by their leaders. It is likely to take time and leadership to implement a significant change to established corporate policy-making processes.

To support the substantial policy development task of establishing road safety priorities, road authorities in LMICs could usefully establish working groups to examine issues and develop detailed and implementable policy recommendations for senior management. Each group would have:

These working groups would report to senior management, which could be convened as a senior road safety planning group on a regular basis. Priority policy issues could include:

An authority with more developed corporate decision making processes could follow a Project Review Committee approach to develop and progress an expanded crash risk reduction programme. The committee would be made up of the senior engineering executives of the organisation and would review presentations by project staff on larger proposed projects on a regular (possibly weekly) basis. Project proponents would be queried on higher-level key issues, (estimated cost, asset management, delivery, environmental and land acquisition, mobility and access, traffic management and road safety).

Safety discussions would centre on measures proposed to improve safety within new projects or the existing safety issues on an existing road which is to be upgraded and measures to be taken to address these. Corporate road safety policies, guidelines and standards would be reviewed and adjusted, or introduced, as a result of these discussions and associated further reviews.

As indicated in Learning and Knowledge Developments in Embedding the Safe System in the Goals and Operational Practice of Road Authorities, the previous exposure to blackspot programmes is relevant, as these activities sensitise a road authority not only to opportunities for improving levels of safety on the network but also to the disadvantages of only treating high-risk locations, leaving lower-risk lengths untreated and less likely to be treated.

The Project Review Committee approach recognises that embedding the Safe System requires an organisation-wide dialogue at the senior management level about network operating responsibilities, as well as a similar dialogue at project or programme-specific levels (e.g. where bicycle paths along existing arterial roads should be located on the cross-section of an upgrade or new road project).

The production of quality policies, guidelines and standards follows as a next step. These will be developed over time and will be quite varied in nature, reflecting the stage of safety development of a road authority and its immediate safety priorities. Further advice on the role of policies, standards and tools and their development is provided in Chapter 9, Infrastructure Safety Management: Policies, Standards, Guidelines and Tools along with examples.

An Example: Some road-safety-related policy gaps that were identified as needing to be addressed by the Indonesian Directorate General of Highways (DGH) in a review in 2013 of the overall strategic plan are summarised below. They are down to earth, practical policy initiatives, including:

For road authorities in LMICs, priority safety issues for policy attention and implementation will often differ from priorities for HIC authorities. For LMICs, policy priorities will usually include:

As an example, the City of Abu Dhabi has worked to develop urban design guidelines for application across the urban streets of the city to improve sustainable safety and amenity for pedestrians, public transit users and cyclists and give these road users priority through these treatments. This outlined in the case study below.

The steps outlined in Setting a New Strategic Objective to Producing Policies and Guidelines from Embedding the Safe System in the Goals and Operational Practice of Road Authorities will provide the guidance required for embedding the Safe System within management and operation of the network. However, there is another step required of road authorities. They need to progressively apply the policies they are developing and to build supportive management systems to ensure their network management activities incorporate all the guidance they have prepared.

A road authority will need to take steps to incorporate safety management systems within its network planning and operations. This can be pursued through measures such as:

Some formalisation of this approach is recommended in time and ISO 39001 provides guidance on how to structure this (see Interventions in Management System Frameworks and Tools).

A road authority will need to progressively assure itself and the community that it is making progress with improving its network safety management and operation. This assurance can be sought through:

For most LMICs, the identification and adoption of specific safety KPIs will be a useful way to measure performance and build accountability over time.

All road safety strategies should have specific KPIs. The introduction of KPIs allows authorities to specify the level of improved road safety achievement sought and/or to encourage active development and achievement of road safety improvement programmes.

One consequence of a lack of high-level road safety KPIs can be the absence of an identifiable separate budget allocation for specific road safety programmes. Funding allocation categories within LMIC road authorities typically include routine maintenance, periodic maintenance, rehabilitation and reconstruction. One of the benefits of a separate allocation for specific safety programmes is the ability to measure overall expenditure on targeted safety works and to determine economic return on investment.

Good network safety performance needs to be considered a major organisational output for a road authority. Over time, safety-related corporate-level KPIs are likely to move from initial introduction in many LMICs to ‘centre stage’ importance in the authority’s overall performance assessment.

A range of more detailed performance indicators will need to be developed to enable progress with implementation of infrastructure safety treatments. Once KPIs are agreed it is necessary to establish how they will be measured and reported, and determine the frequency at which this will take place (see performance indicators discussion in The Road Safety Management System, Effective Management And Use Of Safety Data and Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects). Example KPIs from the Global Plan are provided in Box 7.9.

The Global Plan for the Decade of Action (see The UN Decade of action and global plan) includes performance indicators for the safer roads and mobility pillar. Although these are targeted at the monitoring of activity at global level, they serve as useful examples for use by individual countries. The indicators are categorised as ‘Core’ and ‘Optional’.

Core indicators

Optional indicators

Source: UNRSC, 2011

Programme guidelines are specifications for use by road authority staff of the elements within a potential programme that are to be developed and funded on a priority basis (usually on the basis of benefit-cost ratio or net present value; see Intervention Selection And Prioritisation). They are used by many road authorities to guide preparation of projects that are to be considered in a corporate approval process in various programme funding categories for the coming financial year.

Their development is usually a cooperative process between the relevant central policy area and the regions of a road authority; such processes are required to develop and deliver the approved projects as components of the particular programme. They represent the specification of the proposed annual activity programme which has been agreed between core business areas, regional offices and corporate level, and enable regions to bid in detail for categories of project funding.

An example of this is the introduction of a safety-focused maintenance policy that embeds safety performance criteria in the agreed levels of service of the road network. Modification of these existing practices can deliver measurable safety improvement across the network over time. A review of existing practices and identification of ways to modify current practice to deliver a safer network at the same or similar levels of cost could be carried out as part of annual programme guideline development.

Effective programme guidelines require sufficient lead time for development, and then are used to assist the generation of the annual programme for review, consideration and prioritisation during the budget development period.

There are many variants to this process in different authorities. The important elements are:

It takes time and effort to set up arrangements for new programmes with which the road authority is comfortable. It is suggested that simpler programmes (both development and delivery) in the initial years of development can assist with this transition, especially for LMICs.

Starting with projects that are more straightforward in nature (such as blackspot or blacklength identification and treatment on the existing network and road safety audit activity for new projects) offer a good initial learning platform.

The commencement of safety programmes with blackspot treatments enables staff to understand the necessary analysis of crash costs, the impacts of specific treatment types (such as roundabouts or hard-shoulder widening), and the crash cost reduction benefits of those treatments. As outlined in Establishing Corporate Processes to Develop Policy in Embedding the Safe System in the Goals and Operational Practice of Road Authorities these are necessary skill sets required before a road authority moves on to crash-risk-based identification, and analysis and treatment of network lengths and routes to achieve crash reduction benefits.

Success in the initial years with a simpler programme is likely to lead to increased support for the road safety improvement task from the community and government and to further funding.

Belin M-A, Tillgren P & Vedung E (2012), Vision zero – a road safety policy innovation, International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion Volume 19, Issue 2, 2012, pages 171-179.

Climo, H, Dugdale, M & Rossiter, L (2014), The Safe System in Practice – A sector-wide training programme, Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety, 25, 19-26.

Kostic N, Lipovac K, Radovic M & Vollpracht H, (2013), Improvement of Road Safety Management and Conditions in Republika Srpska, World Road Association (PIARC), Routes/Roads 360, 54-63.

United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) (2011), Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011 – 2020, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Vollpracht, H (2010), They call them coffin roads, World Road Association (PIARC), Routes/Roads 347, 42-52.

Zajc, L (2014), ‘Slovenian experiences on road safety management’, Presentation to Regional Road Safety Capacity Building Workshop, Belgrade, Serbia, 15-16 October 2014