The final step of the risk assessment process is the monitoring, analysis and evaluation of interventions (Figure 12.1)

Figure 12.1 Monitoring and evaluation within the risk assessment process

As described in The Road Safety Management System, monitoring, analysis and evaluation is the ‘systematic and ongoing measurement of road safety outputs and outcomes (intermediate and final), and the evaluation of interventions to achieve the desired focus on results’ (GRSF, 2009). These tasks are often overlooked, but are essential for the effective management of road safety.

Earlier chapters have provided information on the role of monitoring, analysis and evaluation in road safety management, including its importance as part of road safety targets and programmes (The Road Safety Management System, and to a lesser extent, Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects and Design for Road User Characteristics and Compliance); and the role it plays in data requirements (Identifying Data Requirements). This chapter concentrates on the evaluation process at the network and project level, and includes information on the importance of this process as well as how to undertake monitoring and evaluation.

Monitoring refers to the systematic collection of data regarding the performance of a road safety programme or intervention during or after its implementation. Analysis involves the study of data in order to interpret it and its parts, such as determining the contributing factors to crashes. Evaluation involves the analysis of this data to determine the effect of the treatment or programme.

The purpose of the monitoring and evaluation process is to:

A successful evaluation process requires careful planning, which includes collecting baseline data, identifying the aims before implementation, and considering the different methods of analysis that could be used for the evaluation. It is also essential that the results and feedback of the evaluation study are properly circulated amongst stakeholders and other interested agencies.

There are three main types of evaluation. One or more may be appropriate for a study, and this is dependent on the aims of what needs to be evaluated. The three main types of evaluation are:

Both qualitative and quantitative methods can be used for an evaluation study. Qualitative questions are more useful in process and outcome evaluations in the form of focus groups, or open-answer questionnaires, and can be insightful as to why an intervention may not have been successful. Quantitative studies produce more rigorous outputs through the use of controlled trials or before-and-after studies.

As identified in Priority Ranking Methods and Economic Assessment, information on intervention effectiveness is also important in assessing the likely benefits of safety improvements. The evaluation process is important for improving knowledge regarding the effectiveness of different road safety interventions in different types of environments. The use of such information in the selection and prioritisation of interventions is discussed in Intervention Selection And Prioritisation, while this chapter concentrates on methods for monitoring and evaluation. However, agencies must be cautious about generalising the results of an evaluation.

Processes should be established for the collection of relevant data. For those just getting started, this collection could be undertaken as part of a corridor or area demonstration project.

Staff and financial resources need to be provided for monitoring, analysis and evaluation, and key road agency staff and stakeholders should be trained in basic analysis and evaluation methods. Consideration should be given to the storage and maintenance of the data over time.

With limited budgets, it is very important to demonstrate that road safety interventions are effective, and of value. This is particularly important in LMICs where comprehensive action plans have been developed fairly recently with limited funds from central governments and aid agencies. Good information is required on the effectiveness of interventions to ensure that limited available funding is spent in the most effective way. There is currently a large gap in our understanding of how different interventions improve safety in LMICs. Intervention Effectiveness in LMICs in Intervention Options and Selection highlights some of the difficulties in using information from HICs on treatment effectiveness in LMICs. An evidence-based approach is required to improve knowledge on effectiveness of interventions in LMICs, and this can only occur through monitoring and evaluation of interventions in these countries.

Even worse than the inefficient use of limited funding is the possible use of interventions that lead to an increase in crash risk. Unfortunately, this situation does occur in public policy decision making, including those regarding road safety, often as the result of poor information, as a result of behavioural adaptation from road users, or from a poor implementation process. It may also occur due to trade-offs in decision making, whereby safety considerations are not given as high a priority as other issues (such as mobility).

One example that illustrates how a ‘safety’ intervention can produce an increase in risk comes from driver education programmes. Although it may seem unlikely that increased driver training and education would have either no effect or even moderately increase crash risk, this is exactly what has been found. Various studies exist on driver education program. From these studies driver education program may not always have a clear positive effect. These examples indicate the importance of having information on effectiveness before spending limited resources. (Helman et al., 2010, cited in McKenna, 2010; and Williams, 2006, cited in McKenna, 2010).

Monitoring, analysis and evaluation is an important component of infrastructure safety management, it need not be undertaken to the same extent for each project. For example, if a safety intervention is implemented in a particular locality that has already been thoroughly evaluated and deemed beneficial then the requirement for further evaluation may be more limited. Safety treatments that have had little or no use in the locality will need to follow a more thorough evaluation process.

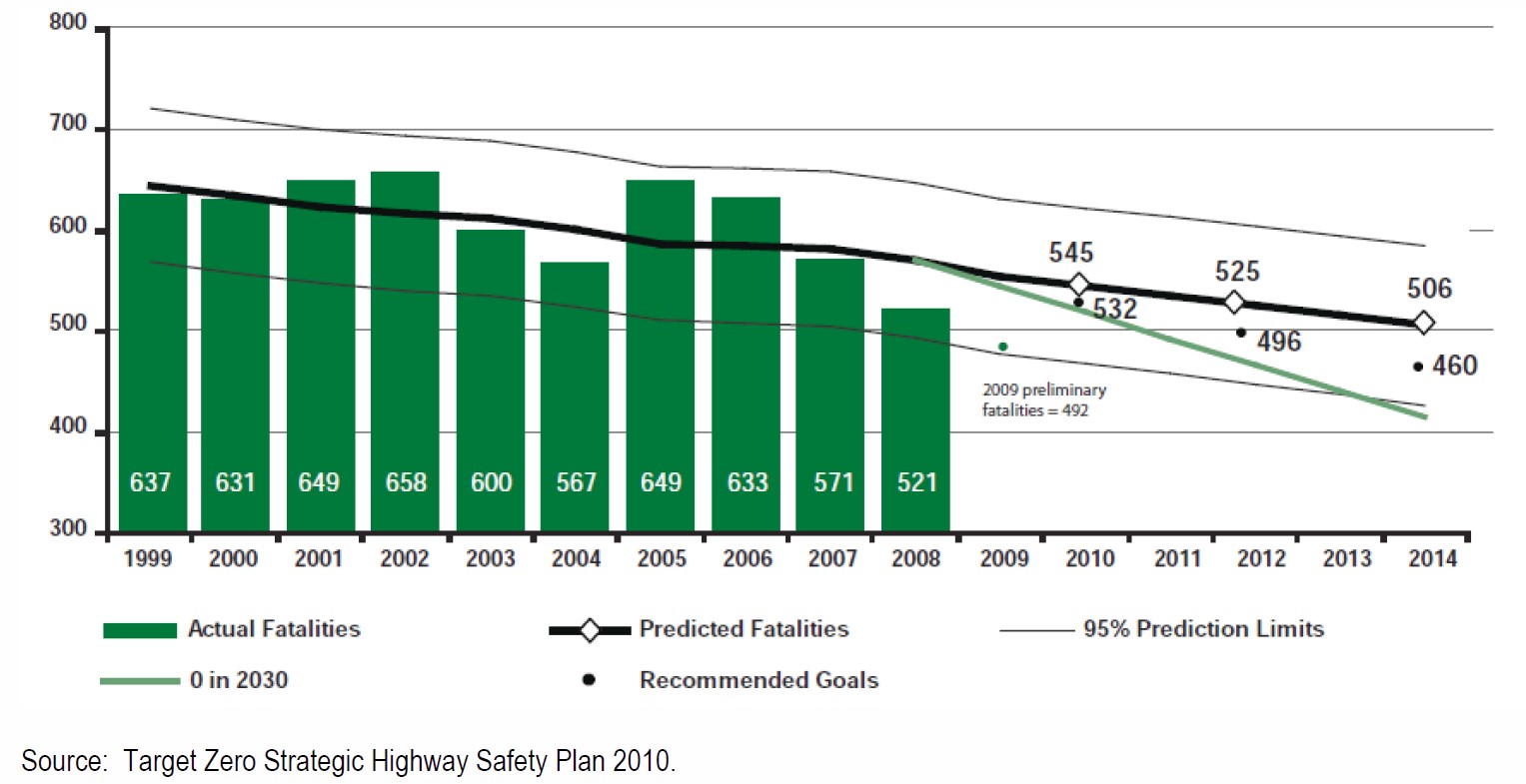

Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects described the process required to set quantifiable road safety targets as part of policy development and plans. As discussed in that chapter, there is a requirement to constantly monitor and analyse progress against these targets. As well as monitoring long- term targets, there is also a need to ensure that relevant agencies and government departments are implementing the improvements outlined in the plan through monitoring of intermediate targets. As an example, the State of Washington in the United States, previously used the Holt Method to forecast data trends to set near term targets and to set intermediate targets for the strategic highway safety plan.. The figure below shows a visual representation. The standard deviation is shown to report a range of what can be expected in the near-term. Also see: Effective Management And Use Of Safety Data.

Figure 1: Setting Intermediate Targets in Washington State, USA

Such monitoring can also help establish whether these activities are having the desired effect on safety outcomes. In many cases, this monitoring will identify adjustments that can be made to help improve safety outcomes. Data requirements for these activities have been outlined in Effective Management And Use Of Safety Data.

The following section provides guidance on how to analyse and evaluate road safety infrastructure interventions. Some of these approaches can be used to help evaluate performance against targets. However, evaluating the success of interventions in meeting targets can be a more complex task because there are often many changes taking place simultaneously. Solutions to this issue include the evaluation of ‘packages’ of treatments (i.e. determine the effect of the combined activities that are related), or the application of statistical modelling to try to determine the impact of individual measures. Whichever approach is taken, the creation of a strong data collection and analysis process is required to ensure that adequate data is collected. This will include the need for data on final outcomes (crash data) and intermediate measures (safety performance indicators, e.g. various behavioural measures, attitude survey information, and infrastructure measures). For further information on data requirements see Chapter 5. For information on evaluation of non infrastructure interventions, there are a number of important reference documents. These include the UK website and toolkit on evaluation of education, training and publicity programmes (http://www.roadsafetyevaluation.com), as well as global good practice documents on helmets (GRSP, 2006) and drink driving (GRSP, 2007), speed (2008), seatbelts and child restraints (GRSP, 2009), two and three-wheeler safety (WHO 2017), road safety legislation (2017 WHO). The Czech Republic case study shows an example of setting and monitoring targets for the countries efforts to reduce number of people killed and injured on its roadways.

Effective decisions regarding the use of road safety infrastructure interventions can only be made with adequate knowledge regarding its effectiveness. The key measure that is used for this assessment is the expected reduction in crashes, expressed as a crash modification factor (CMF) for the intervention. This indicates the degree to which the intervention is expected to reduce crashes. CMFs are also described in detail in Effective Safe System Interventions in Intervention Options And Selection. CMFs help policy-makers in the decision-making process, and the results from previous studies are typically used to provide a realistic estimate of the expected effect (SafetyCube, CMF Clearinghouse). However, there are many gaps in knowledge regarding the effectiveness of interventions.

An international collaboration on effective evaluation for road safety infrastructure interventions has recently been completed. The OECD/ITF (2012) document Sharing Road Safety provided the following key messages:

Some of the key recommendations from this work were that:

The ultimate measure of the success of a road safety policy or intervention is the effect that it has had on crash reduction, particularly the reduction in fatal and serious injuries. Unfortunately, difficulty arises in considering crashes on their own, as it may be necessary to wait several years after the countermeasure or package of measures has been introduced to be able to validate the changes in crash statistics. Given an indication of effectiveness is often required in a shorter timeframe, particularly to determine that nothing has gone wrong, more immediate feedback may be required. Proxy measures for safety might be useful to monitor the effectiveness of schemes (see also Identifying Data Requirements) for the link between intermediate and final outcome measures). These proxy measures are usually observational-type measurements. It is often recommended to conduct an evaluation in two stages: a short-term phase (e.g. 6 months) and a longer-term phase (e.g. 3 to 5 years).

Where practical, the treated site, route or area should be observed immediately after completion of the construction work; with regular visits made in the following days, weeks or months after completion until the team is satisfied that the scheme is operating as expected.

It is recommended that any earlier behavioural measurements made at the investigation stage be repeated later (e.g. traffic conflict counts, speed measurements), as this will help determine/support the need for any further changes, or may in fact prove the success of the intervention. This behavioural study is also required because some features of an intervention may, for instance, produce an unforeseen reaction in road users and subsequently create a potentially hazardous situation. Monitoring and analysis should highlight this problem at an early stage so that appropriate action can be taken quickly to remove this hazard.

At best, it may be possible to alleviate this hazard easily, e.g. by realigning the kerb lines to prevent a hazardous manoeuvre. At worst, it could lead to the complete withdrawal of a scheme and the need to reassess alternative schemes.

Some of the issues that may be relevant to assess include:

It would be impractical to carry out detailed behavioural studies for all minor alterations, but such studies may be particularly important for expensive schemes such as area-wide or mass action treatments.

It may be preferable to allow the scheme to operate for about two months before conducting a behavioural ‘after’ study. This should serve as a ‘settling-in’ period, during which regular users get used to a new road feature and any learning effects have largely disappeared. The evaluation should verify the impacts in terms of safety for all users. The overall effects of a project should be understood as a whole. For example, the implementation of a bike lane can be dangerous if used by motorcyclists.

The following six case study from Malaysia, Puerto Rico, Portugal, Slovakia and Italy provides a number of excellent evaluations on the safety effects of various treatment.

The case study describes a set of safety countermeasures in via Pistoiese (Firenze – Italy), that is an urban collector road classified as a high accident concentration section. A detailed safety study has been undertaken to identify the possible applicable safety countermeasures. Accident analysis, road safety inspections and driving simulation studies were performed. The intervention to be implemented combines physical and perceptual treatments. Read more (PDF, 869 kb).

© ARRB Group

The most important form of evaluation of any safety measure is determining its effect on crashes, and whether the intervention has reduced the number of crashes (particularly fatal and serious injury ones) by the expected amount. Evaluation involves the analysis of crash data by comparing the safety performance before a change was made to the safety performance afterwards. This often involves statistical analysis. To be reasonably sure that the random nature of crashes has been taken into account, it will normally be necessary to wait for several years for a valid result to be available. As mentioned earlier, more immediate feedback is often necessary and sometimes a shorter-term monitoring method may be applied.

Apart from the time-scale issue, there are other factors that complicate the (apparently straightforward) process of assessing the effectiveness of crash changes at treated sites, routes or areas. The main ones to consider are:

Each of these is discussed below.

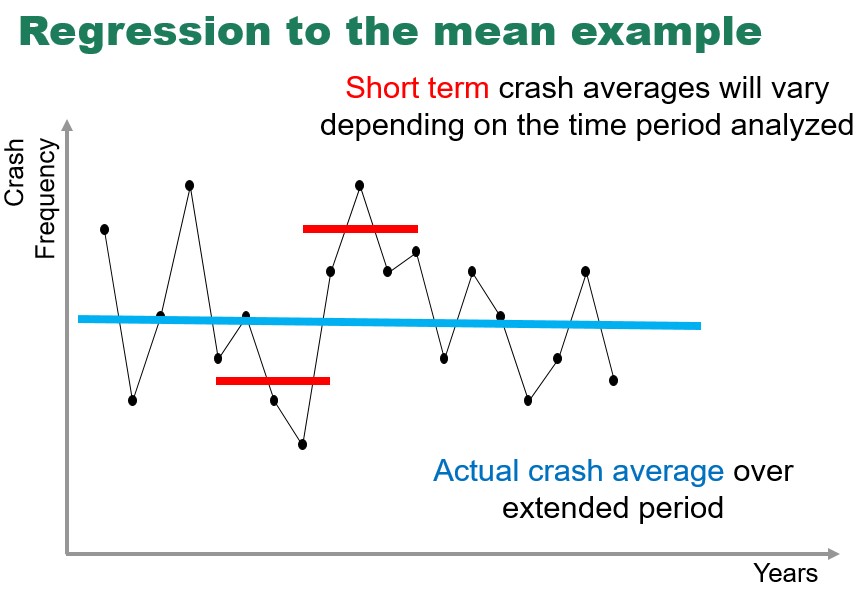

This effect complicates evaluations at high-crash locations. Crash locations for treatment are typically chosen because they were the scene of numerous crashes. In some cases, the high crash numbers may be the result of just one particularly bad year, and this may have happened purely by chance. Crash numbers at such sites will tend to fall in the next year even if no intervention is applied. Even if a three-year period is used, crash occurrence may be due to random fluctuations, and in subsequent years these sites will experience lower numbers. This is known as regression to the mean. It is believed that the regression to the mean effect can overstate the effectiveness of a treatment by 5% to 30%. Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of regression to the mean.

Figure 1: Graph Showing Regression to the Mean

Mountain, Maher and Fawaz (1998) provide a clear example of regression to the mean that can result in overestimation of intervention effectiveness. In a large study covering over 900 sites and 13 612 crashes, they compared crashes occurring during the site identification ‘before’ period, the lag period (the period between a site being selected for treatment and the actual installation of the treatment), and the ‘after’ period. The crash numbers were adjusted to take the different period lengths into account, and the data is summarised in Table 12.1. The difference between the number of crashes occurring in the lag period and the number of crashes occurring in the before period was taken as a measure of the regression to the mean effect.

| Treatment | Biased estimate of reduction due to the treatment (%) | Unbiased estimate of the treatment effect (%) | Estimated reduction due to regression to the mean (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Surface treatments | 46 | 23 | 23 |

Surface treatments – wet road crashes only | 67 | 27 | 40 |

Mini-roundabouts | 68 | 65 | 3 |

Other junction improvements | 42 | 27 | 15 |

Link realignment | 63 | 37 | 26 |

Other link improvements | 34 | 10 | 24 |

Street lighting schemes | 27 | 5 | 22 |

Traffic management schemes | 41 | 22 | 19 |

All treatment types | 43 | 23 | 20 |

Source: Adapted from Mountain, Maher and Fawaz (1998).

The most robust way of accounting for both the regression to the mean effect and changes in the environment may be through the use of control sites that have been chosen in exactly the same way as the treated sites and have been identified as having similar problems, but have been untreated. The choice as to whether a site is treated or is untreated is based on a random allocation. This type of controlled experiment (or randomised control trial) is rare in road safety infrastructure projects as it is difficult to justify not treating a site that has been identified as high risk.

In recent years, the Empirical Bayes approach has emerged as an effective way of minimising the impact of regression to the mean. Although the Empirical Bayes approach is recognised as good practice in road safety evaluation, not all countries (especially those in LMICs) will have experience in using this technique. If not using this recommended approach, at the very least, a before-and-after analysis using comparison sites should be undertaken, with at least three (but preferably five) years of data collected for the before period. This is because the regression to the mean effect does tend to diminish if considered over longer periods of time. For example, in a study conducted in two counties in the UK, Abbess et al. (1981) calculated that regression to the mean had the following effects:

Where the Empirical Bayes approach has not been used, the above allowances could be made when calculating the reduction in crashes produced by the countermeasures.

When evaluating changes in crashes (or for most of the monitoring measures described in Observation in 12.4 Evaluating Road Safety Infrastructure Interventions), other factors not affected by the treatment might still influence that measure, and therefore will have to be taken into account. Examples include a change in the speed limit on roads that include the treated crash site; national or local road safety campaigns; or traffic management schemes that might affect traffic volume (e.g. closure of an intersection near the site, producing a marked change in traffic patterns). Changes related to external factors may be compensated for by comparing the site under study, for the same before and after periods, with comparison sites (sometimes termed ‘control’ sites) that have not been treated. In order for this data to be valid, it is important that these other sites experience exactly the same changes as the site under evaluation.

Comparison data can be collected either by matched pairs or area controls. A matched pair control site involves finding a site that is geographically close to the treated site (but not close enough to be affected by any traffic diversion), and has similar general characteristics. This is so that the control site will be subject to the same local variations that might affect safety (e.g. weather, traffic flows, safety campaigns, etc.).

In practice it may be difficult to find other sites with similar safety problems that will be untreated purely for the sake of statistical analysis. Area comparisons comprising a large number of sites are, therefore, frequently used.

Comparison group sites should be as similar as possible to the treated sites and they should not be affected by the treatment.

There is still some controversy over whether or not the ‘crash migration’ effect exists. It has been found that crashes tend to increase at sites adjoining a successfully treated site, producing an apparent crash transfer or ‘migration’. Why this effect occurs is unclear, but one hypothesis is that drivers are ‘compensating’ for the improved safety at treated sites by being less cautious elsewhere.

Obviously, to detect such an occurrence, the crash frequencies in the surrounding area of the treated sites before and after treatment need to be compared with a suitable comparison group. In other words, the area of an evaluation study needs to be expanded to include routes that may be impacted by the project, and comparison sites must be identified that have not been affected.

However, there are no established techniques yet available to estimate such an effect for a particular site. The first reported occurrence of this feature (Boyle & W, 1984) found an overall crash increase in the surrounding areas of about 9%, and a later study (Persaud, 1987) of a larger number of sites estimated the increase to be 0.2 crashes per site per year.

A study by Austroads (2010) identified the effects that certain interventions have on the redistribution of traffic, and suggest that this may be a cause of migration. If traffic is reduced at the treated location, it is likely that it will be increased at a nearby location (this is likely in all situations, except the rare circumstance where trip numbers are reduced). It is suggested that this redistribution is more likely for certain types of treatments. For these interventions, evaluation of the effects should include a broader geographic area to capture locations where exposure (and therefore risk) may be increased. Interventions identified as potentially causing such an effect included:

There are several key documents that provide detailed accounts of evaluation methods for road safety infrastructure. These include:

One or more of these documents should be consulted for a full account of how to conduct a road safety evaluation.

The ‘gold standard’ in evaluation methodology is a ‘controlled experiment’ or randomised control trial (RCT). As indicated earlier, this approach is very rare in evaluation of infrastructure interventions. This is mainly due to concerns with leaving high risk sites untreated, but is also due to issues such as lack of knowledge regarding this approach. By randomly allocating sites to a treatment or control group, any biases which arise from treating sites with the worst crash history should be eliminated. External factors which come into play as the evaluation proceeds (such as unforeseen enforcement programmes in the area of the trials) are also catered for, as the external factors can be assumed to affect the treatment and control sites equally. The difference between the treatment and control sites in the after period is a true reflection of the influence of the treatment.

The currently recommended approach for evaluation of infrastructure interventions is the Empirical Bayes (or EB) method. Hauer (1997) explains this procedure in its simplest form, which is recommended reading for those wishing to understand the logic behind this approach as it applies to road safety. T

The approach uses the concept of an ‘expected’ number of crashes, or the long-term average, calculated over as long a period as is considered useful. The second concept is the ‘reference population’, or a set of similar sites or routes for which data is available (e.g. all intersections of a certain type in a network). The reference population acts like a comparison group. In the classical version of EB, the number of crashes which would be expected at a treatment site if no intervention had taken place is estimated and compared with the number of crashes that actually occurred. The comparison of the actual number of crashes with the expected number of crashes indicates the extent of the CMF.

A commonly applied method for the evaluation of infrastructure safety is the before-and-after study utilising a comparison group. Even though this approach does not fully address the issue of regression to the mean (although as indicated above, using a longer ‘before’ time period can reduce this effect), it does limit the impact of external factors. The approach compares the outcomes at the treatment sites with the outcomes at a set of comparison sites (sometimes termed ‘control’ sites), which have similar characteristics to the treatment sites in all important aspects, except that the treatment is not installed. This approach assumes that external factors act on both the treatment sites and the comparison sites in an identical way, and so can be measured and allowed for. Since the treatment sites and the comparison sites are subject to the same sets of external variables, any difference in safety outcomes must be due to the treatment.

The most basic form of evaluation (and one that has often been applied) is to simply compare crashes in the period before an intervention is installed with the crashes after (termed a simple or naïve before-and-after study – i.e. without a comparison group). This approach is not recommended, as it does not adequately account for regression to the mean or external variables.

Cross-sectional studies have also been used to try and identify the effects of safety interventions. These studies compare safety performance of sites with a particular safety feature (or features) with sites that do not have the same feature. It is assumed that the difference in safety performance is due to this feature. There are many issues with using this approach (particularly differences between sites other than the feature of interest; and differential crash rates that may have led to the installation of the feature in the first place), therefore it should not be used for this type of evaluation (however, if it is used, the limitations should be well-understood and documented).

In evaluating a particular treatment, the answers to the following questions will usually be required:

The rare and random nature of road crashes can lead to fairly large fluctuations in crash frequencies at a site from year to year, even though there has been no change in the underlying safety level. This extra variability makes the effect of the treatment more difficult to detect, but a test of statistical significance can be used to determine whether the observed change in crashes is likely to have occurred by chance or not.

The main problem with using crash data for evaluation (even assuming high recording accuracy) is distinguishing between changes due to the treatment and changes due to other sources. As explained earlier, even if the selected sites are good comparison groups that take into account the environmental influences, there are other confounding factors that need to be considered.

There are a number of points to take into account when choosing time periods used to compare crashes occurring before and after treatment; these include:

As identified throughout this chapter, there are a number of documents that provide a detailed guide to evaluating intervention effectiveness. There are also various tools to help with this task. Box 12.2 provides a summary of the Countermeasure Evaluation Tool from SafetyAnalyst.

Developed by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), the Countermeasure evaluation tool is part of the SafetyAnalyst suite of tools. It provides step-by-step guidance for conducting evaluation of the benefits of safety interventions using the Empirical Bayes approach. Therefore, it is able to account for the effect of regression to the mean (see above). As well as detecting the overall change in crashes (the CMF), the tool can also identify the effect on specific target crash types. For further details see Harwood et al. (2010) or http://www.safetyanalyst.org/evaltool.htm.

Source: Harwood et al. (2010).

© ARRB Group

AASHTO (2010) Highway Safety Manual, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, Washington, USA.

Abbess, C.D. Jarrett & W, C.C. (1981) Accidents at blackspots: estimating the effectiveness of remedial treatment, with special reference to the “regression to the mean” effect. Traffic Engineering & Control, V22, N10., pp. 532-542

Austroads, (2010), Road Safety Engineering Risk Assessment, Part 2: Crash Risk Migration, Austroads Technical Report AP-T147/10, Sydney, Australia.

Austroads (2012) An Introductory Guide for Evaluating Effectiveness of Road Safety Treatments. Austroads, Sydney, Australia.

Boyle, A.J. & W, C.C. (1984) Accident ‘migration’ after remedial treatment at accident blackspots, Traffic Engineering & Control, V25, N5, pp. 260-267.

Global Road Safety Facility GRSF (2009), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility World Bank, Washington DC.

Gross, F Persaud, B and Lyon, C (2010) Guide to developing quality crash modification factors, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Washington, DC.

GRSP (2006), Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2007), Drinking and driving: a Road Safety Manual for Decision-makers and Practitioners, Global Road Safety Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2008), Speed management: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, GRSP, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2009), Seat-belts and child restraints: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, FIA Foundation for the Automobile and Society, London, United Kingdom.

Harwood, D Torbic, D. Richard, K. & Meyer, M, (2010), SafetyAnalyst: Software Tools for Safety Management of Specific Highway Sites. Federal Highway Administration, McLean, Virginia.

Hauer, E (1997), Observational before-after studies in road safety, Pergamon, Oxford, UK.

Hauer, E. & Byer, P. (1983) Bias-by-selection: the accuracy of an unbiased estimator, Accident Analysis & Prevention, V15, N5, pp.323-328

Kulmala, R. (1994) Measuring the safety effect of road measures at junctions. Accident Analysis & Prevention V26, N6, pp. 781-794.

Maher, M.J. & Mountain, L.J. (1988) The identification of accident blackspots: a comparison of current methods, Accident Analysis & Prevention, V20, N2.

McKenna, F, (2010), Education in Road Safety: Are we getting it ? RAC Foundation, London, UK.

Mountain, L, Maher, M & Fawaz, B, (1998), ‘Improved estimates of the safety effects of accident remedial schemes’, Traffic Engineering and Control, vol. 30 no.10, pp. 554-8.

OECD/ITF (2012) Sharing Road Safety, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris, France.

Persaud, B. (1987) Migration of accident risk after remedial treatment at accident blackspots, Traffic Engineering & Control, V28,N1, pp. 23-26.

Radin Umar, R.S., Mackay, G.M. & Hills, B.L. (1995) Preliminary analysis of motorcycle accidents: short term impacts of the running headlights campaign and regulation in Malaysia, Journal of Traffic Medicine.

W, C.C & Boyle, A.J. (1987) Road accident causation and engineering treatment: a review of current issues. Traffic Engineering & Control, V28, N9, pp. 475-479.

Washington State, Washington State Target Zero Strategic Highway Safety Plan, p. 7

World Health Organization (2017)