This chapter outlines the Safe System approach from first principles to end delivery of safe outcomes, with cross-referencing to the detailed planning and design activities that give effect to a Safe System approach, which are set out in later sections of this manual.

A Safe System approach within the road transport system is built around the premise that death and injury are unacceptable and are avoidable. This approach seeks to ensure that no road user is subject to kinetic energy exchange in a crash which will result in death or serious long-term disabling injury. OECD (2016) endorses the Safe System approach and notes that Safe System principles represent a fundamental shift from traditional road safety thinking, reframing the way in which traffic safety is viewed and managed.

The Safe System represents a major change to past approaches. It overturns the fatalistic view that road traffic injury is the price to be paid for achieving mobility. It sets a goal of eliminating road crash fatalities and serious injuries in the long-term, with interim targets to be set in the years towards road death and serious injury elimination.

This elimination is feasible. It requires system reconfiguration and recognition that the network must eventually be forgiving of routine human (road user) errors. It is important to recognise the fundamental change that road safety agencies, including road authorities, will face in embracing and implementing this Safe System aspiration and in implementing Safe System treatments across their networks (See Responsibilities and Policy for road authority impacts).

ITF (2016) suggest that the key Safe System principles are that:

A video has been produced by the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) describing the Safe System approach, and the role of different parts of the system. This provides a very useful introduction to this topic (See The Difference Between Life and Death – a 20 minute film).

A commitment is needed from agencies to review their road safety capacity (see Safety Management System); to develop understanding of the principles of Safe System and its elements; to adopt a long term goal for elimination of fatalities and serious injuries.

Countries must develop their knowledge to address gaps within the agencies (and of other stakeholders) as to what a Safe System approach is and what practical change this will require in management and intervention approaches. Over time all Safe System elements (See Safe System Elements), and the safety of all road users are to be addressed. Funding needs are to be identified and advocated to government.

Understanding of major crash types (See Crash Causes) should be determined from crash data or if not available, by discussions with police and emergency services workers. Develop a reliable crash data system as soon as possible (See Safety Data).

Road assessment programmes can play a part in identifying higher risk sections of a network and in identifying affordable treatments, especially where reliable crash injury data is not available. Weaknesses in Safe System elements (roads and traffic management - including roadside management and abutting development access controls, see Section 7.3; vehicles, speeds; and road user behaviours) which contribute to fatalities and serious injuries in these crash types should be determined.

In the short term, for new road projects, adoption of Safe System design policies which apply Safe System principles to treatments to reduce fatal crash risk will be developed. Design guidelines would follow subsequently but these would be a substantial development task which requires an incremental medium-term approach.

Seek to improve user behaviour and compliance (See Safe System Principles) across the whole existing network through improved traffic management guidance, reduced speed limits in high risk areas and improved police enforcement, offence penalties and public education See Targets and Strategic Plans for the recommended demonstration project approach.

In the medium to longer term: Carry out progressive retrofitting of the existing system. Do what is feasible to improve infrastructure safety and further improve behaviour and compliance through licensing system reviews and legislative changes re offences. Continue public education campaigns and seek improved vehicle safety regulation and public education.

The Safe System approach is a comprehensive safety philosophy, developed and internationally agreed-upon to form the foundation for safe design and operation of the road transport system. The deficiencies in traditional approaches to achieving a safe road network were highlighted by Tingvall (2005). He noted that the road transport system internationally has traditionally been characterised as follows:

These comments draw attention to the fact that there has been a lack of acceptance of responsibility in this field by most governments. The safest communities (OECD, 2016) will be those that embrace the shift towards a Safe System and begin work now on the interventions required to close the gap between current performance and the performance associated with a genuinely safe road traffic system.

This requires understanding not only of the current system’s safety weaknesses, but also of what change may be possible in the short-term to achieve Safe System compliant outputs. Sufficient management leadership within government road safety agencies (including road authorities), as outlined in Chapter 3, The Road Safety Management System, is essential to achieve meaningful progress in the delivery of these substantially different outputs.

A Safe System will exist when road users are no longer exposed to death or serious injury on the network.

The Safe System approach focuses on eliminating crashes that result in fatal or serious injury outcomes; that is, those crashes that are a major threat to human health. It draws upon the Swedish Vision Zero and the Dutch Sustainable Safety road safety visions and objectives. Safe System Principles provides information on other key elements of the Swedish and Dutch approaches.

The Swedish Vision Zero asserts that human life and health are paramount (Tingvall, 2005) and no long-term trade-off is allowed, reflected in the ethical imperative that “It can never be acceptable that people are killed or seriously injured when moving within the road transport system”. Tingvall (2005) notes that traditionally, mobility has been regarded as a function of the road transport system for which safety is traded-off. However, Vision Zero turns this concept around and resets mobility as being a function of safety (See References(Scope of Road Safety Problem)). That is: no more mobility should be generated than that which is inherently safe for the system. This ethical dimension reflects the principles accepted for workplace safety, where the effectiveness of the working process cannot be traded-off for health risks. Norway (NPRA, 2006), in adopting the Vision Zero goal, has highlighted the ethical approach underpinning it, i.e. “Every human being is unique and irreplaceable and we cannot accept that between 200 and 300 persons lose their lives annually in traffic”. Sweden is looking beyond Vision Zero as well, and in November, 2017 introduced "Moving Beyond Zero." Moving Beyond Zero is a major rethink of the Vision Zero policy and introduces an active transport advocacy campaign.

The objective of the Netherlands Sustainable Safety approach (Wegman & Aarts, 2006) is to prevent road crashes from happening, and where this is not feasible, to reduce the incidence of (severe) injuries whenever possible.

OECD (2016) points out that while Vision Zero is based on an ethical principle to eliminate death and serious injury from the transport system, Sustainable Safety takes elimination of preventable accidents as the starting point and attaches greater weight to cost-effectiveness in determining interventions.

It is clear that this ethical position, which holds that the prime responsibility of a road authority is to support road users to reach the end of each of their trips safely, is being increasingly adopted by jurisdictions. The following literature supports the need for measures to save lives through achieving a ‘forgiving’ system:

The Safe System’s ethical goal of serious casualty elimination will not be achieved overnight. It requires a long-term timeframe for actions to be developed and implemented in successive intermediate timeframes, to deliver incremental serious casualty reductions (to meet interim targets over the medium-term) and support progress towards the long-term goal. The following case studies from Belize and China show two long-term approaches to reducing fatal and serious crashes.

It also requires commitment to interim step-wise targets, which gives prominence to the long-term goal (OECD, 2016; GRSF, 2009; 2012; Breen, 2012).

PIARC (2012), in its National Road Safety Policies and Plans Report, notes that best practice in target setting is represented by government commitment to a long-term goal of zero fatalities with strong interim targets that establish the path to success. Adoption of a long-term Safe System approach is identified good practice for managing for results and is supported by other key international road safety stakeholder organisations as outlined in Road Safety Management. Following the request of the United Nations General Assembly, on November 22, 2017, member states reached consensus on 12 global road safety performance targets. For more information see Developing Global Road Safety Targets. There is an increasing number of countries that have adopted a “Towards Zero” or fatal and serious injury elimination goal — the aspiration underpinning the Safe System approach. This long-term commitment to elimination of road crash fatalities and serious injuries at the highest level of government will influence and support road safety management and road safety policy in a jurisdiction and will be clearly reflected in the proposals described in a strategy and action plan to achieve ambitious interim targets. The following case study from the United States of America, discusses the Minnesota's Towards Zero Deaths initiative.

The safe system approach often requires road agencies to rethink their approach to how projects and programmes are implemented. It is important to begin with some understanding of the how the system is currently operating through objective performance measurement. The first case study discusses the Road Safety Manual which was developed to help the practitioner on the Safe System journey. Some nations have also started the journey through the "Star Rating" system developed as part of iRAP. This is shown in the second case study.

Brussels, Belgium (Source: J. Milton)

The Safe System approach provides a different way to look at crash causation, and at the key crash types that contribute to fatal and serious injury.

The traditional understanding of crash causation supported the perception that the driver or other road user error was the cause of most crashes and was therefore the major issue that needed to be addressed. While road user error is a contributing factor to many crashes, there are a number of key research findings that challenge the traditional allocation of most causation to driver/rider error (human behaviour) and the associated notion that human behaviour can easily be altered (also See the discussion in Designing for Road Users on this issue).

Kimber (2003) suggests past post-crash assessments of crash contribution by researchers resulted in too great a focus on driver behaviour at the time the data was collected. Interventions with potentially greater effect were easily overlooked. Driver behaviour is a wide category and it was easy to populate it by default when the evidence was incomplete or a better explanation was not available. Due to this perceived driver failure predominance, the main priority for many years was to concentrate on measures to change driver behaviour (rather than focusing on reengineering other parts of the road, vehicle or driver system) to eliminate the failures.

This mindset is changing, but the misguided focus on the significance of driver error still remains predominant in too much of the thinking across international communities.

Human error is to be expected. It is unhelpful to regard all human error as being capable of somehow being eliminated and the consequences of it therefore being avoided. When the circumstances of road and vehicle allow, routine driver errors translate into collisions, sometimes with injury or death resulting. A focus on the infrastructure and vehicle safety levels that interact with routine driver error is a much more useful means of identifying actions to reduce serious casualty outcomes.

Elvik and Vaa, (2004) indicate that, even if all road users complied with all road rules, fatalities would only fall by around 60% and injuries by 40%. Specifically, they note that around 37% of fatalities and 63% of serious injuries do not involve non-compliance with road rules. This indicates that routine human error leading to crashes, rather than deliberate or unintentional breaking of road rules, is a feature of human existence and road use.

While achieving compliance with road rules by road users remains critically important, this approach alone will not achieve the desired road safety gains in any country.

As practitioners from LMICs recognise, there is often a lower level of compliance with road rules and a lesser respect for the rule of law in most LMICs than for many HICs. This deliberate reluctance to act in accordance with the law would affect fatality and serious injury rates in these countries and this is one key difference in comparison to serious crash experience in many HICs.

While a substantial potential benefit is available in the medium term through changing this illegal road user behaviour in LMICs, a further focus upon improvements in infrastructure and vehicle safety over the medium to longer term will be essential in providing a forgiving system (a Safe System) for crashes arising from underlying (and not illegal) human error, as is the current and strengthening focus in many HICs. Therefore, research findings from HICs about the role of safer roads and vehicles are very relevant to LMICs.

Stigson (2011) conducted further analysis on the different weaknesses in the traffic system’s traditional components and determined that they play a greater or lesser role in influencing the outcome of crashes. The analysis confirms the potential for road infrastructure to more substantially impact upon fatal crash outcomes for car occupants than other factors in HICs.

While system weaknesses should usefully be analysed for two wheeler, cyclists and pedestrians in HICs and also in LMICs, vehicle safety improvement (as users shift over the next decades from two wheelers to vehicles) and improved behavioural compliance will offer great opportunities for reducing crashes in most LMICs compared to most HICs. However, the potential contribution of safer infrastructure to substantially reduce fatalities should be reinforced with all road authorities.

The movement to a focus on fatal and serious casualty injury reduction through the Safe System approach (as opposed to casualty crash reduction) has had a profound impact on the understanding of key crash types.

The shift in focus from crash numbers to casualties has a subtle but important impact on crash assessment and the strategies to address risk. Different types of crashes will produce different crash outcomes, including greater or lesser numbers of injuries per crash. For example, analysis from New Zealand on crashes and casualties demonstrates this point. Table (NZTA, 2011) shows the proportions of the three most common types of crashes and casualties that result in fatalities and serious injuries for rural roads (excluding motorways).

| Key crash types | % of high severity crashes on New Zealand rural roads | % of high severity casualties on New Zealand rural roads |

|---|---|---|

Run-off-road | 56% | 51% |

Head-on | 19% | 25% |

At intersections | 16% | 16% |

The table shows that 92% of fatal and serious injuries on rural roads in New Zealand are attributed to three key crash types. The table also shows that a higher proportion (1.30 to 1) of severe casualties (fatal and serious injuries) occur through head-on crashes (25%) than is reflected in the proportion of severe head on crashes (19%). This indicates that the head-on crash type is of greater significance for overall fatalities than the severe crash numbers would indicate.

Similarly, analysis of crashes by fatal and serious injury (compared to all injuries) is likely to provide a different picture of the risk across the network.

The relative incidence of various fatal and serious crash types will differ from most HICs to most LMICs due to the differences in traffic environments. The types of vehicles and their relative share of the overall traffic volume are two examples of likely difference. It is essential for the road safety agencies and road authorities to know what the major crash types are in their country and where they are occurring (also see Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes and Assessing Potential Risks and Identifying Issues). Agencies should be in a position to identify the higher fatal and serious injury crash risk lengths of roads on their networks.

The predominant road crash types that result in deaths and serious injuries in high-income countries are typically:

For many low- and middle-income countries, key crash types include:

The case study from India discusses the implementation of a speed regulation system.

CASE STUDY - India: Implementation of speed regulation system on highway A10

An innovation in engineering design practice was piloted in India on the Kamataka State Highway Improvement Project (550km). The project demonstrated how the iRAP Star Rating protocol can be used to rate the safety of a road prior to construction or rehabilitation with information drawn from the road design plans. Final designs for construction are anticipated to provide a reduction in severe injuries of 45% in India. Read more (PDF, 860 kb)

The Safe System approach places requirements on the road safety management system. These requirements include:

The system will ultimately need to protect all road users, including those who act illegally, from death and serious injury. In the interim period the focus should be on protecting those who do not act illegally and those who could be killed or seriously injured by the illegal actions or errors of other road users.

As noted above, as well as road user behaviour, road- and vehicle-related safety factors play a substantial part in fatal injury crashes. Progressive movement towards a Safe System requires all key stakeholders to accept their responsibilities to provide for safe overall operation of the network. This is in addition to the responsibilities that individual road users bear. This concept of ‘shared responsibility’ is at the core of the shift in traditional thinking about road crash contributing factors that a Safe System requires.

The Safe System approach looks to infrastructure design, speed limits and vehicle safety features that individually (and together) minimise violent crash forces. It relies upon adequate education, legislation and enforcement efforts to gain high levels of road user compliance with road rules; effective licensing regimes to control the safety of drivers using the system (particularly novice drivers and riders); and the cancelation of licences when serious offences are committed. A good standard of emergency post-crash care is also needed.

This fundamental shift away from a “blame the road user” focus, to an approach that compels system providers or designers to provide an intrinsically safe traffic environment, is recognised as the key to achieving ambitious road safety outcomes (OECD, 2016).

While individual road users are expected to be alert and to comply with all road rules, the ‘system providers’ — including the government and industry organisations that design, build, maintain and regulate roads and vehicles — have a primary responsibility to provide a safe operating environment for road users (See Box 4.1). This requires recognition of the many other system providers (beyond the road engineers and vehicle suppliers) who impact on use of the network and who also carry a major responsibility for supporting achievement of safer, survivable outcomes.

The studies noted in Crash Causes confirm the fundamental importance of those responsible for delivering safer roads and roadsides, safer travel speeds and safer vehicles, as well as safer behaviours. Road users should not have to operate in a system full of flawed designs that increase the probability of error. Sweden’s Vision Zero “envisages a chain of responsibility that both begins and ends with the system designers (i.e. providers)”. The responsibility chain (Tingvall, 2005) has three steps:

Many challenges are involved in monitoring ongoing performance of the responsibilities of system providers or system designers. They need to accept accountability for their outputs.

While the principle of shared responsibility has been naturally accepted in the road safety strategies of those countries who have adopted the Safe System approach, the necessary substantial (and often subtle) adjustment required to become accepted operating practice will take some time to achieve across agencies (including road authorities).

Road safety responsibilities also extend to the broader community. For example, health professionals have a role in helping their clients to manage their safety on the roads; and parents contribute significantly to the road safety education of their children — not only through their direct supervision of learner drivers, but also as role models through their own driving and road user behaviour. The Danish Road Safety Accident Investigation Board case study provides an example of shared responsibility.

Road Safety decisions should not be made in isolation but should be aligned with broader community values, such as economic; land use planning; human, occupational and environmental health; consumer goals; and mobility and accessibility as outlined in Scope of the Road Safety Problem. There is strong alignment between the Safe System and these goals. The following two case studies show how alignment of policies can be beneficial to safety.

The Safe System approach marks a shift from a sole focus on crash reduction to the elimination of death and serious injury. Well-established safety principles underpin the Safe System approach as set out in Key Developments. Further principles include the following:

As noted earlier, the Safe System approach builds upon the ground-breaking road safety efforts of the Netherlands and Sweden.

Wegman & Aarts (2006) outlines a set of guiding principles (based on the Dutch Sustainable Safety Vision) considered necessary to achieve sustainably safe road traffic. The principles are based on scientific theories and research methods arising from disciplines including psychology, biomechanics and traffic engineering, and are set out in Table 4.2 below.

| Sustainable Safety Principle | Description |

|---|---|

Functionality of roads | Single function of roads as either through roads, distributor roads, or access roads, in a hierarchically structured road network. |

Homogeneity of mass and/or speed and direction | Equality in speed, direction, and mass at medium and high speeds. |

Predictability of road course and road user behaviour by a recognisable road design | Road environment and road user behaviour that support road user expectations through consistency and continuity in road design. |

Forgiveness of the environment and road users | Injury limitation through a forgiving road environment and anticipation of road user behaviour. |

State of awareness by the road user | Ability to assess one’s task capability to handle the driving task. |

Tingvall (2012) commented on the challenges Sweden faces in redefining transport policy principles to reflect Vision Zero (or the Safe System approach):

“You can travel from A to B at 100 km/h and we will make some improvements to this two lane two way rural road to improve your travel safety:

“You can travel at this safe speed from A to B based on the safe system elements which are operating and which will avoid fatal and serious injury in the event of a crash. You can only travel faster if infrastructure safety is improved.” (eg, roundabouts at intersections, median barriers, run off road barriers to protect from roadside objects, etc.)

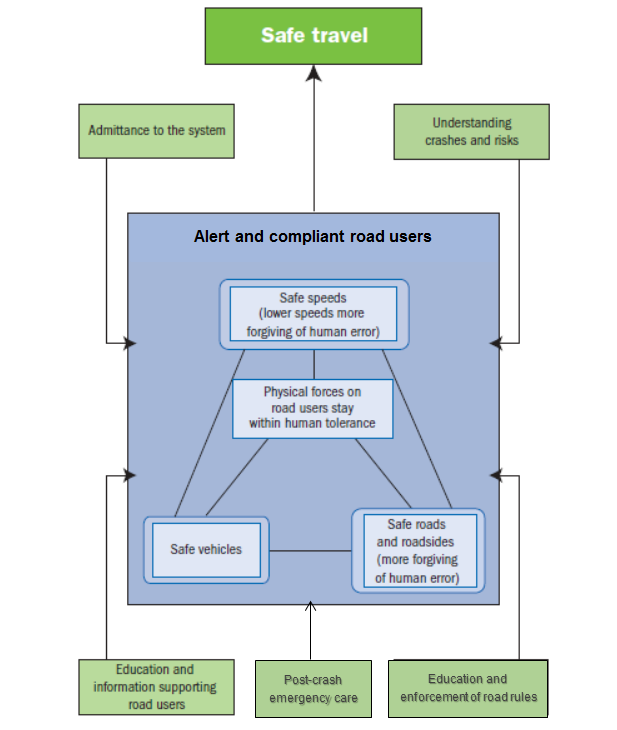

The elements of the integrated, human-centric Safe System model for safe road use and their interactions can be depicted as follows (Figure 4.1):

Figure 4.1: A model of the Safe System approach - Source: Adapted from OECD/ITF, 2008; ATC, 2009.

The Safe System design model has four main elements (including alert and compliant road users) plus five supporting activities that can be adjusted and applied in agreement with the four main elements to assist in making crashes more likely to be survivable.

The four main design elements are:

The key supporting Safe System elements include:

The last three elements in the list above support achieving road user compliance with the road rules.

In summary, for alert and compliant road users, a combination of vehicle safety features, safety characteristics of the infrastructure and travel speed are required, together with effective emergency medical post-crash care, in order to avoid a fatal or disabling serious injury outcome in the event of a crash.

Travel speeds are a critical variable within a Safe System with allowable safe speeds on any part of the network being dependent upon vehicle types (and their protective features), the forgiving and protective nature of the infrastructure and roadsides, the restrictions upon roadside access to the roadway and the presence of vulnerable road users. All of these factors will determine a maximum vehicle speed on each section of the network above which an unacceptable probability of death is likely from any collision.

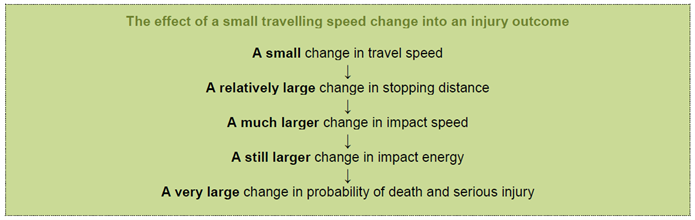

Injury outcomes and the creation of an inherently safe road system are largely dependent on the kinetic energy in the system. At the moment of impact, the force on the body can exceed the body's tolerance.

The amount of kinetic energy (Ek) is calculated according to the following formula:

Ek = 1/2 mv2

where m = mass (kg) and v = velocity (m/s)

The formula shows that kinetic energy does not increase linearly with speed, but with the square of the speed. This has important implications for how speed affects the road safety. A small increase in travel speed can significantly increase the probability of a serious injury outcome.

Source: Austroads (2018)

Reducing speed is one of the most effective ways to improve safety, saving lives and debilitating injuries. However, the opportunities that lowered travel speeds offer to other societal goals are generally under-appreciated. Reducing speed also generates multiple other benefits fundamental to sustainable mobility: reduced climate change impacts of road transport, increased efficiency (fuel and vehicle maintenance), improved inclusion and walkability (Job et. al. 2020)

Job et. al. (2020) highlighted that when taking into account the full range of economic impacts (GHGs, emissions, fuel, etc.), economically optimal speeds are lower than expected and typically lower than prevailing speed limits compared to limited evaluations of impacts based on travel time savings alone.

Speed management can be achieved through a range of interventions including road infrastructure and vehicle technology, as well as enforcement and promotion.

Crash outcomes, especially fatal crash outcomes, are influenced directly by the travel speed of vehicles at the time of impact.

Elvik et al. (2004) report that “Speed has been found to have a very large effect on road safety, probably larger than any other known risk factor. Speed is a risk factor for absolutely all accidents, ranging from the smallest fender-bender (crash) to fatal accidents. The effect of speed is greater for serious injury accidents and fatal accidents than for property damage-only accidents. If government wants to develop a road transport system in which nobody is killed or permanently injured, speed is the most important factor to regulate”.

Table 4.3 from Elvik et al. (2004) sets out the effects of variations in mean speeds on crashes of various severities. This relative change relationship applies on all lengths of road, over comparable periods of time and refers to the effects of changes in mean speed of travel of all vehicles.

| Relative change (%) in the number of accidents or victims | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in speed (%) | -15% | -10% | -5% | +5% | +10% | +15% |

| Accident or injury severity | ||||||

Fatalities | -52 | -38 | -21 | +25 | +54 | +88 |

Serious injuries | -39 | -27 | -14 | +16 | +33 | +52 |

Slight injuries | -22 | -15 | -7 | +8 | +15 | +23 |

All injured road users | -35 | -25 | -13 | +14 | +29 | +46 |

Fatal accidents | -44 | -32 | -17 | +19 | +41 | +65 |

Serious injury accidents | -32 | -22 | -12 | +12 | +25 | +40 |

Slight injury accidents | -18 | -12 | -6 | +6 | +12 | +18 |

All injury accidents | -28 | -19 | -10 | +10 | +21 | +32 |

Property damage only accidents | -15 | -10 | -5 | +5 | +10 | +15 |

Fatal crash outcomes are the crash type most affected by speed variation. As the above table shows, even small changes in speed (+5%) are associated with very large changes in the number of road crash fatalities (+25%).

As indicated in the safety principles above, an important way to reduce fatal or serious injury crash outcomes is through better management of crash energy, so that no individual road user is exposed to crash forces that are likely to result in death or serious injury.

Conditions that support limiting crash energy to levels below which fatal or serious injury crash outcomes are relatively unlikely, are now becoming better understood, but are still not well recognised or applied system-wide in most countries.

A key strategy is therefore to move (over time) to set posted speed limits in response to the level of protection offered by the existing (or improved) road infrastructure and the safety levels of the vehicles and vehicle mix in operation on sections of the network.

Mobility needs to be constrained by Safe System compliance. Future safe infrastructure investment will often be necessary before considering raising the speed limits on sections of the network in order to avoid increased fatalities or serious injuries.

McInerney & Turner state that the discipline of managing energy exchange and related forces currently exists in the fields of structural engineering for buildings and mechanical engineering for machines, but is rarely sighted in the design of roads. For infrastructure to provide the key building blocks for a Safe System, road engineering design practice worldwide must include provision for the management of kinetic energy. For example, there are simulation programs that examine an errant vehicle departure into a roadside environment, which calculate the change in kinetic energy as the errant vehicle encounters roadside hazards. The rate of kinetic energy dissipation can then be translated into differing collision severity potential.

While the Safe System approach has been adopted as the foundation of many countries’ road safety strategies, concept adoption and effective implementation are two different things. Implementation remains a considerable challenge.

The supporting enabler for planning, development and implementation of Safe System interventions is the road safety management system operating in any country (See Safety Management System for guidance).

The potential for road infrastructure safety treatments to provide certain and immediate reduction in crash likelihood and severity is well recognised. With adequate resources, infrastructure has the ability to eliminate nearly all fatal and serious crash outcomes. Many national and provincial road safety strategies have highlighted the role of infrastructure in making progress towards a Safe System.

Some examples of high-performing infrastructure treatments from these and other studies include typical findings (McInerney & Turner, in press; also see Intervention Option and Selection) that:

All road users need to be considered when designing or upgrading road infrastructure. This includes:

Netherlands Sustainable Safety in Safe System - Scientific Safety Principles and their Application outlined the important principle of safe travel speed which underpins a Safe System approach. Critical speed threshold levels in traffic crashes differ depending upon the type of crash being considered.

Table 4.4 presents the crash severity risk associated with travel speeds which are above a specific threshold level for key crash types. The crash types examined are vehicles with a pedestrian or other vulnerable road user, single vehicle side impact into a pole or tree, side impact between vehicles at intersections, head on crashes between vehicles and single vehicle run off road crashes.

| Impact speeds above which chances of survival or avoiding serious injury decrease rapidly | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crash Type | Impact Speed | Example |

Car/Pedestrian or Cyclist | 30 km/h | Where there is a mix of vulnerable road users and motor vehicle traffic |

Car/motorcyclist | ||

Car/Car (Side impact) | 50 km/h | Where there is a likelihood of side impact crashes (e.g. intersections or access points). |

Car/Car (Head-on) | 70 km/h | Where there is no separation between opposing traffic streams |

In certain parts of the transport network, such as high standard freeways, the risk of crash outcomes involving high levels of energy transfer (and therefore being fatal) is low in relation to the total distance traveled by vehicles on freeway standard links.

These freeways would typically have no at-grade intersections, would have median barriers installed to prevent head-on crashes, and side barriers installed to protect vehicle occupants from roadside objects, and would also segregate vulnerable road user activity such as pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists from higher speed traffic.

In these circumstances, and subject to limitations on vehicle flow volumes per lane, higher operating speeds (such as 100 or 110 km/h) can generally be safely supported for vehicles with a high standard of safety features.

On the other hand, for two-lane, two-way roads in rural environments with unprotected roadside hazards, frequent intersections, unsealed shoulders and variable standards of horizontal and vertical geometry, the risks of serious casualty crash outcomes are much higher.

Table 4.4 illustrates that for these situations, even for a vehicle with the best currently available safety features, the road cannot support a travel speed much above 50 to 70 km/h if fatalities are to be avoided. If roadside hazards are protected (with barriers) and intersections are treated to reduce speeds to 50 km/h the travel speeds on the road can be 70 km/h. The addition of median barriers would enable higher operating speeds to be considered.

Where motorcycles are a large proportion of the traffic, lower speed limits, perhaps 40 km/h, may be necessary.

Lower speed in urban areas is also critical to improving road safety. Speed limits must be adapted to the prevailing traffic situation and to groups of different road users often using the same space. Complementary infrastructure measures such as speed humps and small roundabouts at key locations can help to ensure that speeds are controlled effectively to ensure that vulnerable road users are not exposed to impact speeds above 30km/h.

On higher-order urban arterial or distributor roads the function and use can be prioritised around achieving high traffic flows on road sections, whilst managing exchange at intersections or dedicated mid-block facilities. On these roads, vehicles can drive somewhat faster and tend to travel longer distances. Speed management on these roads should be supported by camera based (fixed or flexible) speed limit enforcement on corridors and at traffic lights. Pedestrians and cyclists can cross at intersections or dedicated mid-block facilities with appropriate localised speed management in place. Ultimately, the aim is to reduce exposure to high-speed motor vehicles, particularly at conflict points.

On the other hand, lower-order roads such as access roads must be managed to facilitate exchange between different road users at lower speed. Speeds in these areas and on these roads are low, not through police enforcement, but by traffic calming and speed management measures. In some areas it may be appropriate to limit vehicle access.

Below is a case study that illustrates the effectiveness of lowered speed limits in urban road environments.

The following four case studies from New Zealand, Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia show how each country is improving road safety. New Zealand uses a safe systems approach with Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia using the iRAP to assess the risk on the road network to allow for safety plan and programme development.

Speed management is at the centre of developing a safe road system. Where infrastructure safety cannot be improved in the foreseeable future and a road has a high crash risk, then reviews of speed limits, supported by appropriate and competent enforcement to support compliance, are a critically important option. Support through targeted infrastructure measures to achieve lower speeds should be considered.

For example, lowering 100 km/h speed limits to 90 km/h may reduce mean speeds by 4 to 5 km/h if there is a reasonable level of enforcement. The scientific and evidence-based research shows that this will deliver a reduction of up to some 20% in the fatalities occurring on these lengths of roads (e.g. (Sliogeris, 1992). This of course assumes some enforcement support.

Since 1996, vehicle safety (or at least, car occupant safety) has been subjected to market forces rather than solely relying upon regulation throughout Europe through EuroNCAP (European New Car Assessment Programme). There is wide acknowledgment that this enhanced approach to advancing rapid development in vehicle safety has been successful. The automotive industry has reacted very quickly to the expectations of the market with regard to car occupant protection. Other New Car Assessment Programmes (NCAP) have been introduced in many regions and countries (Australasia, Japan and many more). The introduction of Electronic Stability Control/Programme (ESC or ESP) in vehicles has been very successful, with unexpected high effectiveness and a market penetration that is quicker than any other previous example (Tingvall, 2005). ESC is now a mainstream part of NCAP ratings.

The opportunities from new safety technologies in vehicles, which are now available or likely to become available, together with the level of inherent crashworthiness of many new vehicles in HICs are remarkable. These benefits should be sought by LMICs as an early priority. LatinCAP in Latin America and ASEAN NCAP are two examples of recent extension of NCAP to LMICs, which will arm consumers with safety information and drive market change. Furthermore, Global NCAP has recently been established and is likely to be highly influential.

Appropriate promotion of the benefits of safety features and overall vehicle safety levels needs to be carried out by road safety agencies. Road authorities should develop their awareness of these new vehicle safety features, particularly ways in which specific infrastructure treatments could leverage improvement in crash outcomes. Road safety agency actions (VicRoads, 2013) could include:

Progress with emerging technologies such as collision avoidance, intelligent speed adaptation, and inbuilt alcohol and fatigue detectors should be monitored by road safety agencies. Pilot studies have been conducted in many vehicle fleets internationally for research purposes in order to establish costs and benefits.

Other initiatives that countries need to pursue include:

Younger drivers should be made aware of the safest used vehicles available in the market in relevant price brackets to encourage their purchase and improve the chances of survival of young drivers in their higher risk early years of driving.

Developments in heavy vehicle safety include ESC responsive braking systems, and fatigue and speed monitoring equipment. New Truck Assessment Programmes may emerge in coming years for heavy vehicle prime movers. Again, road safety agencies need to be aware of these developments.

Many opportunities for improvement exist in the vehicle safety features available to LMIC markets. There are reports of vehicles imported from other countries without safety features fitted, which are standard inclusions in the automobile supplier’s home market (this is reportedly in an endeavour to limit costs). Some countries impose higher rates of tax on safety equipment in vehicles as a misplaced luxury item revenue raising measure, which discourages their fitment. Some key issues are:

© ARRB Group

Maximising road user behaviour that is compliant with road rules remains an important issue. This requires the presence and active implementation of effective legislative arrangements; data systems for vehicles, driver licensing and offences (and their linkage); enforcement; justice system support; and offence processing, as well as follow-up capacities.

Human error, rather than deliberate illegal behaviour, is an important contributor to fatal and serious crashes. Measures to reduce the prospect of human error need to be taken to guide use of the network. Clear consistent guidance and reasonable information processing demands upon the road users along a route is necessary to reduce uncertainty and indecision. These issues are discussed in detail in Design for Road user Characteristics and Compliance, but key issues include:

Developing a respected and effective police enforcement capability requires high-level management competence, good standards of governance, quality research to guide efforts, and a strong results focus.

Progress in LMICs will depend heavily on substantial expert support to accelerate a ‘learning by doing’ approach. A key thread running throughout this manual is practical guidance concerning the implementation of the Safe System approach. A suggested path for road safety agencies in LMICs for moving from weak to stronger institutional capacity, by implementing effective practice through demonstration programmes (or projects), is outlined in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies, Plans and Projects. The programmes should include area-based projects involving all relevant agencies and some national level policy reviews. This approach will support the production of steady improvement in road safety results from all agencies.

Development of a more complete understanding and uptake of a Safe System approach, after adoption as official policy by a country, will take time. It will rely upon a continuous improvement process that examines and implements options, often in innovative ways, to improve performance.

While the key principles of a Safe System are well established (OECD, 2008 and 2016) and underpin the UN Global Plan for the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety (WHO, 2021), the challenge now is to translate these aspirations into practical policy implementation. This is especially important in low-and middle-income countries, where the burden of road injury is highest.

A joint International Transport Forum - World Bank Working Group on "Implementing the Safe System" has developed a theoretical framework to guide those seeking to implement the Safe System approach (ITF, 2022). The framework describes how to improve safety across each of the Safe System pillars through the various key components of a Safe System

The framework provides a mechanism to help identify the current level of Safe System progress, which can be applied to a project, region, country, or organisation, as well as to interventions and activities.. It can be tailored to the relevant stage of Safe System development (emerging, advancing, mature). The framework makes it possible to evaluate the extent to which an existing or planned road-safety project can be considered to align with the Safe System approach and where there is room for improvement.

The Safe System framework serves several possible purposes:

The Safe System framework is structured around three dimensions:

The five key components build on the four fundamental principles of a Safe System by adding institutional governance as a critical enabler of a Safe System. Institutional government is required to organise government intervention covering research, funding, legislation, regulation and licencing and requires mechanisms for coordinating and funding actions as well as maintaining a focus on delivering improved road safety outcomes.

The Safe System framework is based on a matrix that can be used to describe any example of a Safe System intervention based on two dimensions: key components and pillars (see Table 4.5). Within such a matrix it is possible to define the current level of alignment to Safe System for an individual cell or any combination of cells as well as to evaluate the expected level of progress that would occur through improvements leading to better Safe System alignment. In each of the cells, improvements in safety can be made, Safe System principles can be implemented and assessed, and opportunities for improvement can be identified.

To assess progress towards a Safe System and to identify implementation gaps the framework also includes five possible stages of Safe System development (see Table 4.6) applicable to any country, region or city. At one end of the scale, an emerging system combines straightforward interventions and an initial process of co-operation and integration. At the other, a mature system combines sophisticated interventions and progress towards an ideal situation. For some countries or cities working towards Safe System implementation progress may be in the starting stage in some cells, and in the emerging or advancing stage in other cells.

At a strategic level the framework examines the combination of key components and pillars in terms of a conceptual alignment with the Safe System. For example, speed limits that aim to prevent exposure to large forces (refer Cell 4.4 or Table 4.5) are set based on human vulnerability and supported by road design, enforcement , driver education and vehicle technologies. At an operational level the framework outlines descriptions of what road-safety situations to expect in each of the three different stages of development of Safe System implementation. An example three-dimensional framework for Safer Speeds (refer Cell 4.4 of Table 4.5) is presented in Box 4.4.

The Working Group also present lessons from 17 case studies of road-safety interventions across the Safe System with reference to the Safe System framework in the Safe System Approach in Action research report. The case studies demonstrate that there is no simple recipe for successful implementation of the safe System approach and requires tailor-made adjustments depending on context including consideration of the specific socio-economic circumstance of each country, city or region.

Understand what a Safe System would look like.

The following four case studies from New Zealand, Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia show how each country is improving road safety. New Zealand uses a safe systems approach with Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia using the iRAP to assess the risk on the road network to allow for safety plan and programme development.

Australian Transport Council (2009), National Road Safety Action Plan, Canberra, Australia.

Australian Transport Council (2011), National Road Safety Strategy 2011-2020, Canberra, Australia.

Austroads, (2012), Effectiveness of Road Safety Engineering Treatments, AP-R422-12, Austroads, Sydney, Australia.

Austroads, (2018), Towards Safe System Infrastructure: A compendium of Current Knowledge, AP-R560-18, Austroads. Sydney, Australia.

BITRE, (2012), Evaluation of the National Black Spot Program, Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics, Canberra, Australia.

Bliss, T & Breen, J (2009). Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility World Bank, Washington DC

Bliss, T & Breen, J (2011).Improving Road Safety Performance: Lessons From International Experience. A resource paper prepared for the World Bank , Washington (unpublished).

Bliss, T & Breen, J (2013), Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Breen, J (2012), Managing for Ambitious Road Safety Results, 23rd Westminster Lecture on Road Safety, 2nd UN Lecture in the Decade of Action, Parliamentary Advisory Council for Transport safety (PACTS), November 2012, London.

Elvik, R, Vaa,T (2004), The Handbook of Road Safety Measures, TOI, Norway

Elvik, R, Christensen P, Amundsen A, (2004) Speed and Road Accidents, an evaluation of the Power Model, TOI, Norway

FHWA, (2013), CMF Clearinghouse website, http://www.cmfclearinghouse.org/, accessed 30th July - 2013.

Global Road Safety Partnership, Geneva, (2008) Speed management: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, Module 1.

ITF (2022), The Safe System Approach in Action, Research Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

Job, RFS. & Mbugua, LW. (2020). Road Crash Trauma, Climate Change, Pollution and the Total Costs of Speed: Six graphs that tell the story. GRSF Note 2020 . I. Washington DC: Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank.

Kimber, R (2003), Traffic and Accidents: Are the Risks Too High? TRL, Lecture June 2003, Imperial College London.

Larsson, M., Candappa, N.L., and Corben, B.F., (2003), Flexible Barrier Systems Along High-Speed Roads – a Lifesaving Opportunity , Monash University Accident Research Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

McInerney R, Turner B, Infrastructure: A key building block for a Safe System, The International Handbook of Road Safety, Monash University and FIA Foundation.

Ministry of Transport, (2010), Safer Journeys, New Zealand’s road safety strategy 2010–2020, NZ Ministry of Transport, New Zealand.

Norwegian Public Roads Administration, (2006) Vision, Strategy and Targets for Road Traffic Safety in Norway, 2006 – 2015,National Police Directorate, Directorate of Health and Social Welfare, Norwegian Council for Road Safety.

NZ Transport Agency (NZTA), (2011), High Risk Rural Roads Guide, New Zealand Transport Agency, Wellington, New Zealand.

OECD (2008), Towards Zero: Achieving Ambitious Road Safety Targets Through a Safe System Approach, OECD, Paris

OECD (2016), Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System, OECD, Paris.

PIARC (2012), Comparison of National Road Safety Policies and Plans, PIARC Technical Committee C.2 Safer Road Operations, Report 2012R31EN, The World Road Association, Paris.

Sliogeris J (1992), 110 kilometre per hour speed limit: evaluation of road safety effects, Report No. GR 92-8, VicRoads, Melbourne.

Stigson H, Kullgren A & Krafft M, (2011) Use of Car Crashes Resulting in Injuries To Identify System Weaknesses , Paper presented at the 22nd International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV). Washington DC, USA. DOT/NHTSA http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/pdf/esv/esv22/22ESV-000338.pdf

Tingvall, C. (2005) The 7th European Transport Safety Lecture, Europe and its road safety vision – how far to zero? Swedish Road Administration.

Tingvall, C and Haworth, N (1999) Vision Zero - An ethical approach to safety and mobility, 6th ITE International Conference Road Safety & Traffic Enforcement: Beyond 2000, Melbourne.

Tylsoand Declaration (2007), https://online4.ineko.se/trafikverket/Product/Detail/44598

Western Australia Road Safety Council, (2009) Towards Zero – Road safety Strategy, To Reduce Road Trauma in Western Australia 2008-2020.

Wegman, F & Aarts, L (2006) Advancing Sustainable Safety: National Road Safety Outlook for 2005-2020, SWOV Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam, The Netherlands.

WHO (2004) World Report on road traffic injury prevention, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

WHO (2013) Global Status Report on Road Safety, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

Wramborg, P. (2005) A new approach to a safe and sustainable road structure and street design for urban areas. Proceedings of the Road Safety on Four Continents Conference, Warsaw, Poland.

Wundersitz LN, Baldock MRJ (2011), The relative contribution of system failures and extreme behaviour in South Australian crashes, CASR, Adelaide, Australia.