Comprehensive safety data is required for effective road safety management. Safety data is essential for an evidence-based approach, particularly in producing results-focused strategies, action programmes and projects; identifying key crash types and locations; diagnosing the causes of serious and fatal injury in road traffic crashes; selecting treatments; and monitoring and evaluating progress. The establishment and support of data systems is specifically identified as part of the Global Plan for the Decade of Action, with Pillar 1 (Road Safety Management) highlighting the importance of this activity (UNRSC, 2011).

Crash data is a key type of safety data, which can provide a valuable source of information to assist in road safety management. However, this is only one type of data required for the effective management of road safety. Crash data needs to be supplemented by other information, including road inventory and survey data of key behaviours, enforcement data, road network and vehicle fleet safety, and emergency and medical system quality. This data is important in providing intermediate measures of safety. In LMICs where crash injury databases are not fully established or operational, such survey data is particularly important for the measurement and targeting of safety problems. Road safety management capacity reviews in LMICs indicate weak capacity for identification and measurement of road safety problems. As such, there is a need to build capacity to improve road safety data collection, storage, analysis and sharing.

This chapter provides information on the types of data required to effectively manage safety; the establishment of data systems; and the collection and use of this data. It also provides guidance on combining the different types of safety data to manage road safety more effectively.

Uses of this data can be found throughout this manual, including on:

Much of this chapter discusses the effective management of safety data at network level (e.g. for the whole country). However, it is recognised that establishment of a national data source (although essential) may be some way off for some countries. At the very least, the information in this chapter should be used to commence the collection of data on high risk routes, including through corridor and area demonstration projects (see Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects).

As indicated elsewhere in this manual, the focus for effective road safety management is on the elimination of death and serious injury (both of which are defined in Identifying Data Requirements), and this is also where greatest efforts should be made in the collection of safety data. Information on fatal and serious injuries, and the crash types (such as those identified in The Safe System Approach) and factors that lead to such injuries, should form the highest priority in data collection. However, there are also important uses for data on minor injuries and even non-injury crashes, and such information should also be collected where possible.

Countries must assess what safety-related information they already collect, who the key stakeholders (collectors and users) are; how this data is used; and what further information is required. Identifying Data Requirements and Establishing and Maintaining Crash Data Systems discuss these issues.

Countries must commence collection of ‘final outcome’ injury data (especially fatal and serious injury data). Initially this may come from high risk routes or corridors (usually high volume national roads). This is discussed in Establishing and Maintaining Crash Data Systems.

Countries must also start collecting ‘intermediate outcome’ data or information on performance indicators (see Identifying Data Requirements). Information on road and roadside elements is a high priority, and can be used to identify problems and solutions; even in the absence of detailed crash data (see Non Crash Data and Recording Systems). Other intermediate data includes compliance data (such as speed, drink-driving and helmet wearing rates; Non Crash Data and Recording Systems). This data can be used to identify issues and solutions, as well as in the broader management of road safety outcomes.

There are a wide variety of uses for safety data, with many different users. As identified later in Analysis of Data and Using Data to Improve Safety, safety data can be used by policy-makers, traffic engineers, police, the health sector, the research community, insurance companies, prosecutors, vehicle manufacturers and others. Although summary data (particularly on crash fatalities) is available in most countries, more detailed information is required to fulfill the requirements of these users. Without this collection of data, it is not possible to take an evidence based approach to the management of road safety.

WHO (2010) provides discussion on the use of data for a public health approach to road safety. This document provides a comprehensive account of crash data systems, including their place in effective road safety management, and their establishment and use. It is essential reading on this topic, particularly for those working within LMICs who wish to establish or improve upon a crash data system. This document suggests a cyclic approach of:

This process is then repeated.

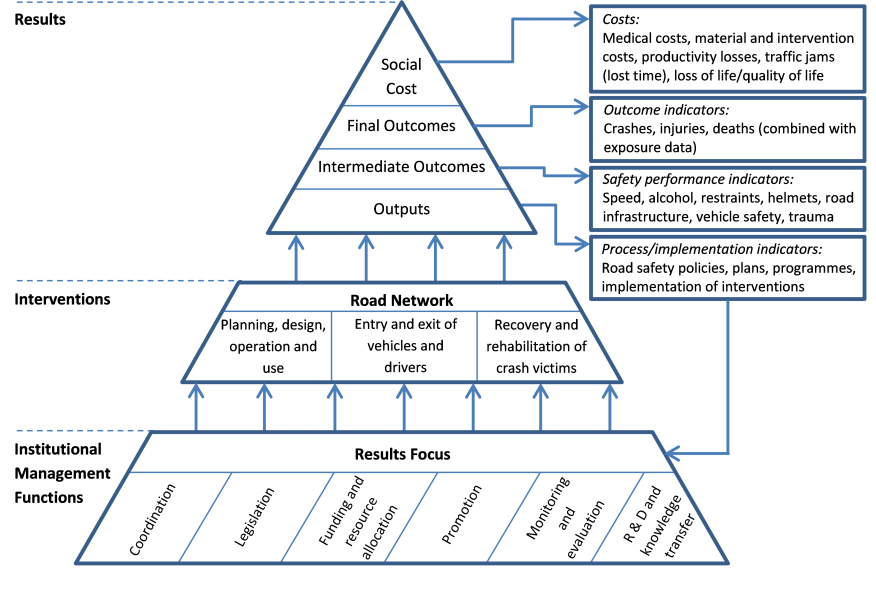

WHO (2010) also provides guidance on the linkage between safety data and effective safety management (Figure 5.1), giving a framework for the collection and use of this data. The WHO document makes it clear that crash data alone is not sufficient to manage safety, but rather it must be used in combination with other sources of information. This additional information is required to better interpret risks, thereby assisting in the monitoring of performance and achievement of results.

Figure 5.1 Data requirements for road safety management - Source: Adapted from WHO, (2010); GRSF, (2009).

As identified in Figure 5.1 and Box 5.1 (and further discussed in WHO, 2010; GRSF, 2009, 2013), the desired results or outcomes of road safety management are expressed as goals and targets, and occur at a number of different but related levels. These include institutional outputs from the policies, programmes and projects that have been implemented, which influence a range of intermediate outcomes. These intermediate outcomes subsequently influence final outcomes. Ultimately, these should reduce fatal and serious injury, in alignment with Safe System outcomes.

Final outcomes: Outcome indicators may include the number of fatalities and serious injuries, crashes relating to certain road users (e.g. pedestrians, motorcyclists) or types (e.g. intersection, head-on), crash rates (e.g. crashes per population, vehicle registrations, or amount of travel)

Intermediate outcomes: Safety performance indicators may include behavioural measures such as average vehicle speed, drink-driving, helmet wearing rates, seatbelt wearing, attitude survey information; vehicle safety ratings; infrastructure measures, including road safety ratings, % of high volume high speed roads that are divided by a median, % of roads where pedestrians are present with adequate footpaths; and post-crash care indicators such as emergency vehicle response times.

Outputs: Process/implementation indicators may include the policies, plans or programmes that have been implemented and details of this implementation (e.g. campaigns to promote seatbelt use, hours of additional speed enforcement, investment in safe road infrastructure, number of new ambulances).

For example, analysis of data may have identified vehicle speed as a risk factor. A policy to improve compliance with speed limits will require an increase in speed enforcement. The output results of this intervention would be evidence of this increase in enforcement. Intermediate outcome measures might include the percentage of drivers exceeding the speed limit at selected locations. Changes in this measure (i.e. a reduction in speeding motorists) would help identify whether the intervention is having the desired effect. The final outcome indicators would include total deaths and serious injuries (ideally including a record of those that were identified as being speed-related), proving the ultimate benefit of this intervention.

Although crash data is a primary source of safety-related information, other data sources also serve a very important role. There is growing recognition of the use of asset data (including road design features) in road safety, and in many cases this information may already be collected and available for use. As identified later in this chapter, many countries do not have accurate information on crashes, and until such data is available, information about road design features and key safety behaviours provides an important means of identifying high risk locations and ways to address them.

Often different sources of information will be available on similar issues. Although multiple sources of information can be useful to help understand road safety issues more fully, it can also lead to confusion if the sources provide conflicting information. Differences can result from inaccuracies in data or differences in how the data is collected (see Quality and Under-reporting for further discussion of these issues). Where there is potential for confusion from the use of multiple sources of information, it is important to select a ‘single source of truth’ from a data source that will ultimately inform decision-making. Once this source of information is selected, justification needs to be provided as to why this source is preferred.

Different terms for injury severity are included throughout this manual. Definitions for different types of injury are provided in Box 5.2.

Fatal injury: any person killed immediately or dying within 30 days as a result of a road traffic injury accident, excluding suicides.

Serious injury: Injury that requires admission to hospital for at least 24 hours, or specialist attention, such as fractures, concussions, severe shock and severe lacerations. Some countries have adopted the Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (MAIS), and suggested that serious injury be defined as MAIS3+.

Other/minor injury: Injury that requires little or no medical attention (e.g. sprains, bruises, superficial cuts and scratches).

Property damage/non-injury: No injury is sustained as a result of the crash but there is damage to vehicles and/or property.

Source: WHO, (2010).

This section provides guidance on the establishment and maintenance of crash data systems. Information on the collection and use of other sources of data can be found in the following sections. Full details on the establishment and maintenance of crash data systems can be found in WHO (2010). The following is a summary of key issues.

Identified effective practice acknowledges that no single crash injury database will provide enough information to give a complete picture of road traffic injuries or to fully understand the underlying injury mechanisms (IRTAD, 2011). A number of countries which have improved their road safety performance use both crash injury data collected by the police as well as health sector data.

National crash data are typically collected by police (WHO (2013) reports that over 70% of countries use police data as the primary source), and entered into crash database systems for easy analysis and annual reporting. In some circumstances, data are collected from hospitals, or from both of these sources. The use of health sector data for meaningful injury classification at country level is necessary to complement police data and to provide an optimal means of defining serious injury. IRTAD (2011) recommends that police data should remain the primary source of road crash statistics, but that this should be complemented by hospital data due to data quality issues and to identify levels of under-reporting (see Section 5.4). Furthermore, in-depth data is needed from crash injury research to lead to meaningful conclusions concerning crash and injury causation.

The police are well placed to collect information on crashes as they are often called to the scene. Alternatively, they may receive information about the crash following the event. Attendance at the crash scene allows for collection of detailed information that is useful for identifying crash causes and possible solutions.

A crash report form is typically completed (traditionally a paper-based form, although recently computer-based systems have been used), allowing collection of quite detailed information on the crash. Key variables typically collected include:

Examples of crash report forms, including the types of detail that should be collected as a minimum can be found in WHO (2010). The advice provided in the WHO document is based on the European Common Accident Dataset (CADaS). In addition, a number of countries have developed their own minimum criteria. For example, the US has a Model Minimum Uniform Crash Criteria (further information is available on a dedicated website at http://www.mmucc.us/).

A balance needs to be reached between collecting the required information, and the time it takes to perform this task. If too much burden is placed on the police, it is less likely that the crash report form will be completed. Police are key stakeholders in the establishment and continued collection and use of crash data, and should be included at each stage of the process.

Hospital data is used to identify levels of under-reporting or to obtain better injury information, particularly when police report data is not available or is inadequate. IRTAD (2011) suggests that because of under-reporting of crash data, hospital data should also be collected, and is the next most useful source of information for crash statistics.

Encouraged by the WHO and other institutions, medical authorities have established international recording systems that include road traffic injury. In particular, the International Classification of Diseases and related Health Problems (ICD) and the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) coding systems are used widely. IRTAD (2011) recommend that an internationally agreed definition of ‘serious’ injury be developed, and that the Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (MAIS) be used as the basis for defining crash injury severity. This scale is based on maximum injury severity for any of nine parts of the body. A score of 3 or greater for one or more regions of the body (MAIS3+) is recommended as the point at which an injury is considered to be serious. An example of the use GIS analysis and hospital data from Thailand is provided below.

A further example is provided in the case study from Egypt, demonstrating the integration of data from different sources, as well as the use of this data by various key stakeholders.

‘Vital registration’ data can be used as a source of information on road deaths. This information comes from death certificates completed by doctors which state the cause of death. WHO (2010) reports that around 40% of WHO member countries collect vital registration data of the detail required for monitoring road traffic deaths. WHO and other organizations have instituted an international registration system that includes those injured in traffic crashes.

Other sources of data on crashes can come from emergency services, tow truck drivers, members of the public, insurance companies, etc. However, it is important to recognise that the quality and extent of this information may be limited when compared to police and hospital reported data.

Before establishing a new crash database system (or improving a current system), it is recommended that a situational assessment be undertaken (WHO, 2010). This involves:

These same steps are also required when establishing or improving on the collection of non-crash data (see Non Crash Data and Recording Systems).

A stakeholder analysis involves identifying organisations and individuals who have (or should have) a role in the collection and use of road safety data. Critical stakeholders will include police, transport agencies and health departments, but there are likely to be many others.

An assessment of data sources is required to determine what information is already collected, and the quality of the data. This is often a significant problem in many countries.

An end user assessment involves understanding who the key users are and, how these key stakeholders use the information. This knowledge will help improve the usability of the data.

An environmental analysis involves understanding the political environment and critical partnerships required for the successful collection, analysis and use of the data. Without this understanding and appropriate collaboration, it is likely that collection and use of crash data will be severely hindered. There are many examples where expensive crash data systems have been established, but data has not been entered into the system due to inadequate communications and poor cooperation.

Following this situational assessment, the recommended process for establishing a crash database system is to:

Crash location is a key element in collecting and analysing data, particular for road engineers. Without this information, it is not possible to determine what locations to treat in the future. In addition, if the crash location is known (whether from police reports or other sources of data), there is potential to link this crash data to asset or other data sources (see Analysis of Data and Using Data to Improve Safety). This information may be of use in identifying other road-based elements that may have contributed to the crash risk.

Several methods are available for the accurate location of crashes, including the use of global positioning systems, reference to a local landmark (e.g. a link-node system), or reference to a route kilometre marker post (a linear referencing system).

Historically, crash data records were kept in paper-based filing systems, but now computerised database systems are used to store information on crashes. This allows relatively easy analysis of data, and is particularly useful in the identification of trends, high risk locations or areas, key crash types, etc. There are a number of computer software packages available for this task. At a minimum, such a system should have the capacity to:

Crash data systems have become very advanced in recent years, with features added that allow quicker and more useful analysis. WHO (2010) and Turner and Hore-Lacy (2010) provide a list of other desirable features of crash data systems. These include:

An example of the successful implementation of a crash data system is provided in the case study below from Cambodia.

The Swedish Strada system is a unique database that integrates police and hospital data. It is important to recognise that although this linkage provides valuable additional information, it does occur at additional cost. Further details are provided in the Swedish case study.

Some countries have undertaken in-depth studies of serious crashes to provide a more thorough understanding of crash causation factors and possible solutions. Such studies typically investigate a sample of high severity crashes. As an example, in the UK, the ‘On the Spot’ project collected detailed and high-quality crash information over two regions. More than 2000 variables were collected for each incident based on scene investigation soon after the crash occurred, as well as follow-up communication with medical services and local government. The information was analysed to provide insight about human involvement, vehicle design, and highway design in crash and injury causation. Mansfield et al. (2008) provide an initial analysis of around 2000 incidents from this program. Such investigation can provide far more detail than what is typically available through a crash report, and to a higher degree of reliability.

Similar examples can be found in many other countries, including the USA, Germany, France, Malaysia, India and Australia. Some of these programmes have been in place for many years, and have produced large amounts of valuable information. One of the key outputs from the EU DaCoTA project (which collected and analysed data from European countries on various road safety topics) was guidance on the collection of such data, as well as standardised procedures (Thomas et al., 2013). A Pan-European In-depth Accident Investigation Network has been established, and tools such as an online manual for in-depth road accident investigations have been developed (see http://dacota-investigation-manual.eu).

The US has established the second Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP2). SHRP2 is perhaps the most comprehensive database of information on factors occurring before and during crashes and near-crash events. The information collected includes data from the Naturalistic Driving Study (NDS) database. This dataset includes information from over 2300 drivers, collected through equipment installed in their own vehicles, and through normal driving. The massive amount of data collected through the NDS is supplemented through the Roadway Information Database (RID) which includes comprehensive information on road elements in the study areas as well as other relevant data (including crash data). This globally significant database is expected to provide the research basis for studies on driver performance and behaviour. More information can be found at http://www.trb.org/StrategicHighwayResearchProgram2SHRP2/Pages/Safety_153.aspx.

UDRIVE is the first large-scale European naturalistic driving study using cars, trucks and powered-two wheelers. The acronym stands for “European naturalistic Driving and Riding for Infrastructure & Vehicle safety and Environment”. Whilst road transport is necessary for the exchange of goods and people. There are significant negative consequences to road safety and the environment. To meet EU Target crashes and vehicle emissions will need to be reduced, with new approaches to achieve these targets developed. It is the aim of UDRIVE to provide a better understanding road user behaviour leading to crashes and wasted vehicle emissions.

Sharing of data from different sources is required for the comprehensive collection, analysis and integration of data. Efficient data sharing, particularly between the police and the highway authority, is essential for good practice road safety management.

However, it is important to note that some organisations may be reluctant to share certain data, particularly personal identifiers, due to the issues it poses surrounding the privacy and anonymity of those involved. One response is to collect the personal details on a separate page of the crash report form (e.g. name and address information). This page can then be removed before sending the remaining pages on to partner agencies. In some cases, it may be necessary to develop appropriate privacy policies to ensure this issue is addressed, or for certain variables to be removed to prevent the identification of individuals.

Crash data on its own is a valuable source of information on crash risk, and when combined with other sources of data, this value can be greatly increased. The following section discusses some of the other data sources, while Analysis of Data and Using Data to Improve Safety discusses combining these sources.

Crash data is generally considered a key source of information when assessing and treating risk. However, in some countries, particularly LMICs, crash data may not be reliable or available at all. Additional surveys and data sources other than crash data may be the only reliable source of safety data available. As discussed in Identifying Data Requirements, this additional information (safety performance indicators) is also important in road safety management. These enable assessment of different policies, programmes and projects to identify their effect on road safety outcomes. This occurs through the collection and assessment of details on the interventions implemented and the intermediate outcomes.

A variety of other data sources are available, including information on road design and features, traffic data, survey data and exposure data.

Road inventory data are a major source of information that can assist in assessing safety. Because the impact of different road elements is well known, different elements or combinations of elements can provide vital insight into crash problems, including the key crash types contributing to fatal and serious injury outcomes (see The Safe System Approach). The following data are of particular use:

This presents a basic list of relevant road element types, but there are many other factors that may have an influence on safety outcomes. The International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) collects around 70 attributes (see http://www.irap.org/about-irap-3/methodology for details of these attributes, and Proactive Identification for more information on iRAP, and Box for examples of the data collection undertaken in Mexico). In the United States, the Model Inventory of Roadway Elements (MIRE) provides a list of 202 elements that may be needed for making road safety decisions. Further information on MIRE can be found at https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/rsdp/mire.aspx.

Road features need to be spatially located (ideally through a GIS-based system) to allow effective analysis and cross-linkage.

Road inventory data relevant to road safety may already exist (e.g. through road asset database systems) or it might need to be collected. A situational assessment should be performed to see whether this data exists (see Establishing and Maintaining Crash Data Systems). Road inventory data has traditionally been used for road safety audit or inspection (see Assessing Potential Risks and Identifying Issues), but in more recent times, methods have been developed to quantify the likely safety outcomes based on these elements. The case study below shows Mexico's efforts to collect data on 46,000 km of its Federal Highways.

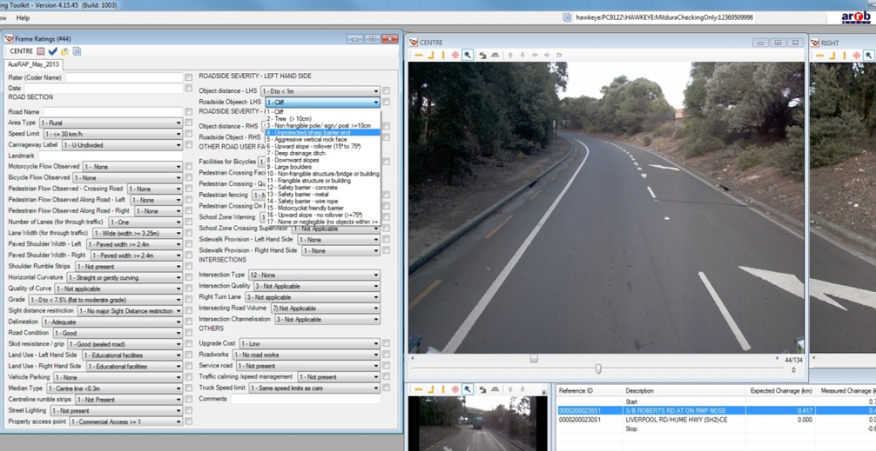

The collection of this data can be based on ad hoc approaches (e.g. through periodic inspection, public complaints, etc.), but should ideally be through a comprehensive programme conducted on a regular basis. The most common approach involves the collection of data through video images, and subsequent rating or coding of this data by trained experts. This information is then fed into a database or asset register (see Box 5.3).

For more extensive data gathering, computer-aided collection can be undertaken using a tablet or laptop, or information can be collected via video and coded safely back in the office. With a tablet, information is added to a database while travelling along the road of interest. Touch screen technology is typically used to select relevant road variables. Different symbols may be displayed on screen to facilitate quick data entry. As mentioned earlier, it is often difficult to enter all relevant variables when travelling at high speeds or in busy environments, and so video is often recorded to assist in later data entry and checking.

Another option involves the desktop assessment of video data. One or more video cameras can be used to collect data along the network of interest. A single camera can be used to gather information in a forward direction. Alternatively, more cameras can be used to allow better collection of road and roadside information. This video imagery is then used to code the variables of interest. The video images can be calibrated to allow measurement for more accurate collection of information (such as road width or distance to roadside hazards) and to ensure accurate spatial location of assets.

Video images are assessed, and can be paused to study more complex environments. Information from the images is added to a database for later analysis. This data entry may be through a dropdown menu system or manual population of a database. Data is typically collected for a discrete length of road (e.g. a 10 m section).

Figure 5.4: Populating a database with safety-related inventory data.

New technologies are being developed that will assist in more automated collection of road and roadside data. As an example, it is possible to collect information on features such as road width, horizontal and vertical alignment, and road surface condition using Light detection and ranging (LiDAR) and other vehicle sensors.

Traffic data is important to collect and analyse, particularly traffic volumes (or Average Annual Daily Traffic, AADT). This data can be used to generate crash rates, which provide a good indication of safety performance, including the safety performance of specific routes, road types or even infrastructure elements. Other types of traffic data include the traffic mix (e.g. percentage of different vehicle type; motorcyclists, bicyclists and pedestrians) and vehicle speeds (mean and 85th percentile speeds, compliance with speed limits). Traffic data can be collected using manual traffic counts or through automated means (e.g. pneumatic tubes or permanent data collection devices installed in the pavement).

Aside from traffic data, other sources of exposure data include population data (total number of people; number by each age group) for an area or country. This data is typically available from national census data. Vehicle registration data is also often collected and used.

Attitude surveys collect information on the views of drivers, other road users and residents. This information is considered an important source of feedback for assessing the effectiveness of a new programme or treatment, and can provide insight into driver behaviour (for example, low compliance levels with the posted speed limit).

Information on the number of police checks (e.g. for speed, alcohol, restraint use), number of violations (e.g. number of vehicles speeding; motorcycle riders without helmets), and number of drivers punished (e.g. fined, penalties provided or imprisoned) are all useful measures. These will help assess the impact of new policies or actions on safety outcomes.

In addition to the data sources mentioned above, other useful information can be gathered from the following sources, where available:

Other types of compliance data are discussed in the following section.

Often traffic data and driver behaviour data are not readily available. There is no set list of additional data that must be collected, and given the cost of any type of data collection, careful thought needs to be given to this task, regardless of whether this is conducted at national level or for specific locations. Additional data should be collected when there is a need for it, and collection of this data should be cost-effective.

The following section provides a brief description of some of the more common data surveys performed, as well as different methods that can be used. References to useful material is also provided.

A spot speed survey involves the collection of a sample of speeds at a specific road location, or at a number of locations. This can then be used to determine the speed distribution of vehicles, which is useful for the following reasons:

Vehicle speeds can be measured using manual methods (radar or laser guns, stop watch), or using automatic methods (loops or tubes). Automatic methods are better for studies that require a larger sample. Loops and tubes can also record more than just average speeds, such as traffic volumes, vehicle turning movements and traffic mix. These components are essential to understanding the safety issues that exist at a location. The GRSP Speed Manual (GRSP, 2008) and the UK government (DTR, 2001) provide in-depth guides to speed and volume measurements and how to manage speed-related safety issues. See case study on speed data collection in India.

GRSP has developed two separate manuals, one dedicated to seatbelts and child restraints (GRSP, 2009) and the other dedicated to helmets (GRSP, 2006). Each of the manuals provides information on how to assess the extent of non-seatbelt and non-helmet use in a project region, as well as how to design, implement and evaluate a programme to target these issues. With regard to measuring seatbelt and helmet usage, the guides list possible sources of this information, as well as how to collect the data through conducting community surveys and observational studies.

Much like measuring helmet and seatbelt usage, GRSP has developed a road safety manual for drink-driving (GRSP, 2007). This provides information on how to assess the situation and choose priority actions, as well as how to design, implement and evaluate a drinking and driving programme.

The guide suggests collecting data from relevant authorities, such as the police, road authorities and health sectors, to understand the size of the problem. Data on the level of compliance with existing laws can be collected through a combination of crash data (i.e. crashes involving drivers and riders with Blood Alcohol Content (BAC) levels exceeding the legal limit), the number of alcohol offences detected by police, the percentage of drivers stopped with a BAC over the legal limit, and by performing driver surveys (GRSP, 2007).

There are a variety of other intermediate outcomes that could be measured, depending on the interventions implemented.

As for crash data, it is important that survey data be recorded in a way that can be analysed easily. It is also beneficial for the system to be developed so that data can be linked with other data sources. This is particularly important for surveys that cover a broad geographic area (such as traffic volume, asset or population data). Such systems may already exist for this data. A common method is to link data by location using a Geographic Information System (GIS). These systems can typically store information that is linked geographically for future analysis. Different types of data can be added to such systems as a ‘layer’, allowing more powerful assessment of risk (see Analysis of Data and Using Data to Improve Safety).

When collecting, managing or utilising road safety data, it is important to remember that data quality can be compromised at any stage of the data process. This can be due to:

There are a number of consequences associated with poor data quality and under-reporting of crash data (Austroads, 2005; OECD, 2007). Some include:

This section will consider factors that affect data quality, as well as methods for studying inconsistencies in data and how to improve data quality. Although this section concentrates on crash data, quality issues are also relevant to non-crash data, and care needs to be taken in the collection and interpretation of this.

Data can sometimes be recorded incorrectly by the police or data entry staff. A major issue to note is that the person who fills in the form at the scene is, in most instances, not the same person who enters the data into the database (OECD, 2007). Missing, incomplete and incorrect data is often unintentional and is the result of human error. Due to officer priorities and workloads, the police cannot always attend the scene of a crash or may not have the time to completely fill out the crash report (which can be made worse by unnecessarily long data collection forms). Unclear variable definitions, as discussed in the next section, can also result in incomplete or incorrect data entry. Similar issues can also occur with non-crash data. For example, road asset data can be coded incorrectly, or data entry errors made during the analysis of speed data.

© ARRB Group

The definition of each variable (crash type, injury severity, location, etc.) can differ between data sources (for example, police crash files, hospital records, insurance claims), jurisdictions and countries. This can lead to complications in the identification of crashes of interest, the comparison of datasets, and the evaluation of data quality within a dataset. Common confusing definitions are discussed below.

The most common categories of injury severity are fatal, serious/severe and slight/minor injury. However, the exact methods used by police and hospital staff to determine which injuries fit into which severity categories can be problematic.

A recurring issue when comparing datasets from different countries is the timeframe that applies to ‘fatal’ injuries and crashes. The 30-day rule defines a fatal crash as when any person is killed immediately or dies within 30 days as a result of a road crash injury, excluding suicides. The 30 day rule is the most common classification used around the world, particularly by high- and middle income countries (WHO, 2010). Other countries, particularly lower-income countries, use the definitions of ‘at the scene’ or ‘within 24 hours’ to classify fatalities, which can create inconsistencies between databases. Adjustment factors have been developed to account for this (WHO, 2010); however, this assumes that similar proportions of vulnerable road users exist in each system, which is not necessarily the case (WHO, 2010).

The 30-day rule also implies that there is some coordination between the police officers who attended the scene and hospital staff in order to check for updates on patient status after 30 days. This is often not the case due to different priorities and workloads of those involved (WHO, 2010). The same issue arises with regard to non-fatal injury classification: a serious/severe injury is often classified as ‘admission to hospital’; however, police often classify this as all people who leave the scene in an ambulance (Austroads, 2005). Similarly, there is variation in what hospitals consider to be a ‘serious injury’ (see IRTAD 2011 for a detailed discussion of this issue). An increasing number of patients are being referred to specialist clinics (e.g. fracture clinics) instead of being admitted to hospital. Therefore, in some databases it is difficult to tell whether trends showing fewer admissions are a result of a change in the severity of crashes or a change in the health care management system (Ward, Lyons & Thoreau, 2006). IRTAD (2011) recommends that serious injury should be determined by trained hospital staff and not the police at the scene of a crash. In reality, such checks on crash severity outcome are often not made, and it is to the police in attendance to determine the severity outcome.

In some countries ‘property damage only’ or ‘non-injury’ crashes are required to be reported, and in others they are not. Sometimes the level of damage must exceed a certain monetary limit before it must be reported. Such additional information can be of use, especially in the identification of crash locations and likely causation, although it does entail a higher cost in terms of data collection and entry.

The definition of a road traffic crash may incorporate or exclude crashes involving non-motorised vehicles. It may also exclude crashes that occur on private roadways or in off-road locations such as parks and parking lots. On the other hand, some countries collect information regardless of the location (WHO, 2010).

Another common issue is that hospital outpatient files often simply focus on the nature of the injury (e.g. broken femur) and sometimes neglect to mention the external cause of the injury. This can make it practically impossible to identify which cases are crash-related, and it also reduces the information available to identify and treat crash locations (WHO, 2010).

There are a number of different methods used to determine the location of a crash (as discussed in Establishing and Maintaining Crash Data System). Each of these methods can be subject to error, which can lead to inaccurate or non specific crash locations recorded by police. This can make it difficult to assess the significance of particular crash locations.

Under-reporting can occur at any point in the data collection and data entry processes. WHO (2010) discusses the factors contributing to under-reporting in police data and health facility data in detail. Under-reporting often varies with crash severity, transport mode, road user types involved, victim age, and the crash location. Common findings are that (Austroads, 2005; Ward, Lyons, Thoreau, 2006):

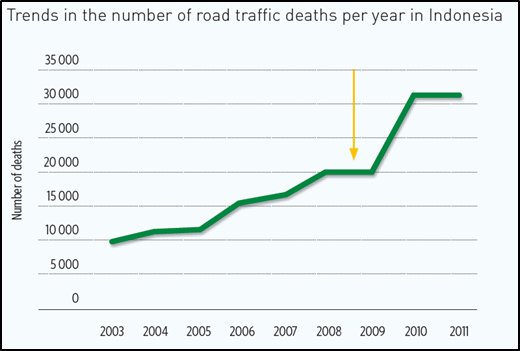

This under-reporting issue can be a significant problem in all types of countries, but has been a particular issue in LMICs (see Box 5.4 and Box 5.5).

Figure 5.5 - Source: WHO, (2013).

However, as indicated by WHO (2013), this activity had the unintended outcome of indicating a substantial increase in road crashes for 2010. This apparent increase is not a result of an actual increase in road deaths, but rather an improvement in the recording of existing deaths. Several countries are experiencing similar apparent increases in road deaths, when in reality the level of data accuracy has improved. The improved data allows for better identification and management of road safety issues. However, the impression that crashes are increasing substantially is an issue that also needs to be managed.

Source: WHO, (2013).

It is typically the case that higher levels of severity have better levels of reporting. Many countries (especially in HICs) record all fatal crashes, and have reasonable records of more serious injury (e.g. hospitalisation). Information for minor injury is typically less well reported. One quick way to determine the likely scale of under-reporting rates for non-fatal crashes is to compare the ratios for fatal crashes to other crash types between countries or regions. Although a number of factors need to be considered (e.g. road types, vehicle fleet, average speeds, etc.), the discrepancy in these ratios can indicate differences in reporting rates.

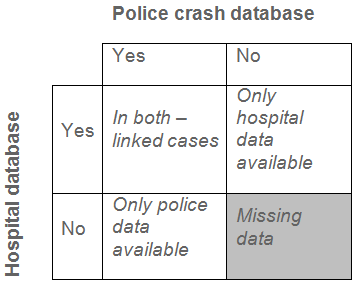

Datasets can be assessed for under-reporting levels and data quality by comparison with other databases. A common comparison to make is between police crash data and hospital in-patient data. Another source is to use insurance claim data. Although these evaluations are very useful, it is not possible to determine the real number of total road crashes as there is no way to know the exact intersection of the two databases (OECD, 2007). There will be some crashes that are recorded in police crash report databases, but as victims are not always sent or admitted to hospital (i.e. in property damage only or minor injury crashes), they do not always appear in the hospital database. Conversely, there will undoubtedly be hospital injury records that are not crash related.

Matching hospital and police data allows cases to be checked for accuracy (ensuring the information provided in both databases is the same) and also provides a basis to estimate the proportion of under-reported cases in both the police and hospital files, as shown in the diagram below (OECD, 2007).

Figure 5.6 - source : OECD, 2007.

A common problem with this technique is that some countries do not allow the release of victim names and sometimes even personal identification codes. Cases can then only be linked by other characteristics, such as time, date and location (Austroads, 2005). Data can only be reliably maintained when the data quality is regularly monitored. WHO (2010) and IRTAD (2011) provide details on methods for assessing data quality and under-reporting rates.

It is typically not possible to successfully collect data for every crash on a network, but not all crashes need to be reported to be able to draw conclusions and identify key priorities to improve road safety (Austroads, 2005; ; FHWA, 2017). However, the more comprehensive the data set, the higher the reliability.

The main steps to improving data quality include:

Section 3.4.1 of WHO (2010) discusses in detail how the above steps can be put into action. It discusses effective solutions such as the benefits of data entry systems with built-in checks to minimise mistakes, and engaging with police so that they see the value and importance of this task and their role within it. It is also important to acknowledge that a balance must be found in the number of details the police must record at a crash scene. Too many questions will lead to incomplete or missing crash reports, whereas too few will limit essential details that are required for future analysis.

Crash data can be extremely useful to a number of agencies and individuals, including:

This section considers the availability of crash data, different users, and current international cooperative efforts to improve crash data.

Crash data is useless to organisations that cannot access it. Appropriate methods for distributing data should be developed for each agency that requires it, through the use of statistical reports, newsletters, websites and workshops (WHO, 2010). If the funding is available, an excellent way to make crash data available is through the use of online public searchable databases, which can provide customised reports based on location, injury type, or other crash characteristics (WHO, 2010). An example of such a system is provided in Box 5.6.

Another effective method to distribute data is through the media, which can act as an agent of change by influencing public and political opinions.

It is important to remember that regardless of the method of distribution, those responsible for crash data also hold the responsibility to protect the privacy of individuals involved. Steps can be taken to assist with this as outlined in WHO (2010).

Data can be used to raise awareness about particular road safety issues, and to act as evidence and draw support for a certain policy, programme or allocation of resources (WHO, 2010). Common advocacy activities include workshops, news reports and campaigns. Advocacy is an important part of road safety – it can be the source of funding and public support. It is important to note that any advocacy material must take the target audience and the context of the recommendation/cause into account in order to have a desirable affect. WHO (2010) provides a number of tips for developing advocacy messages for policy-makers. The Cambodia case study demonstrates the use of road safety data for advocacy purposes.

Road safety engineers are often the most common users of police-based crash databases for road safety work. Crash data is used to identify high crash risk sites, as well as possible identification of risk factors that are specific to the site. This is explained in further detail in Assessing Potential Risks and Identifying Issues.

In the identification of problematic crash locations, target groups or particular risk factors, policy makers use crash data to approximate the size of the problem in terms of counts, severity, trends and the costs of road traffic injuries (WHO, 2010). It is therefore important that these individuals have access to crash characteristics, such as age group, crash type and road user group, so that they can make informed decisions about which high-risk problems get priority and what solutions can be effectively implemented.

Police can also utilise crash data to target enforcement towards a particular issue or location. It is important that the police receive regular feedback so that they can see how their efforts in the collection of crash data, and in traffic enforcement, are having a positive impact (WHO, 2010).

Crash data is essential to evaluate treatments and policies that have been introduced. Evaluations provide a knowledge base about the effectiveness of a given treatment, as well as ensuring that current programmes are providing the expected and desired results.

New analyses can strengthen the known effectiveness of an initiative, such as through the development of crash modification factors (CMFs). Further information is provided in Monitoring and Evaluation of Road Safety on the monitoring, analysis and evaluation of road safety countermeasures, including the effectiveness of treatments and development of CMFs.

International cooperation is essential for data coordination and benchmarking. International assessments can help to identify and monitor national road safety issues, as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of any methods implemented on a wider scale. Benchmarking (through a comparison of safety performance with similar peer countries, regions, cities, etc.) can lead to the identification of road safety issues that need to be addressed. It is important to note that this cannot be achieved unless there is consistency across crash variable definitions. Coordination also helps countries and governments to improve their road safety data quality and collection systems (see Box 5.7).

Figure 5.8 - Source: OECD/ITF, (2014).

In 1988, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) established the International Road Traffic and Accident Database (IRTAD). This database includes crash and traffic data from over 30 countries, which is continuously updated and analysed for trends.

The database includes data such as crash severity, road user group and road user age, and also includes relevant country details such as population, vehicle composition, road network length and seatbelt usage rates. This has allowed very useful benchmarking to occur, allowing comparison of fatality rates (e.g. road fatalities per 100,000 population) between countries.

The IRTAD Group is a working group consisting of road safety experts and statisticians from all over the world. Its main objective is to contribute to international cooperation on safety data and analysis. This is achieved through the exchange of data collection and reporting systems and trends in road safety policies, research and publications on key and emerging issues in road safety and through providing advice on specific road safety issues to member countries.

The IRTAD Group is also in charge of the development of the IRTAD network and database coverage, twinning programmes to assist LMICs in improving their data collection and reporting systems, the IRTAD Conference, and publication of the Annual Report. It also provides standardised definition and methodologies for comparison purposes (e.g. defining injury and crash severities)

Source: OECD/ITF, (2014).

Within the framework of its outreach strategy in LMICs, IRTAD has launched a twinning programme to assist countries. IRTAD is working with a number of organisations in an effort to assist LMICs improve their data collection methods and database setup and management. Several such arrangements exist, including twinning between Cambodia and the Netherlands, Jamaica and the UK, and Argentina and Spain. Other partnerships are currently being developed. The case study in Box 5.15 provides information on the twinning arrangements between Argentina and Spain. Box 5.16 provides details of a broader regional observatory in Latin America. Box 5.17 provides details of the IRTAD/OISEVI Buenos Aires declaration on better safety data for better road safety outcomes.

Example of data collection and use of data are shown in the following two case studies, highlighting Argentina and Spain, as well as the Ibero-American Road Safety Observatory.

In November 2013, 40 countries met at the Joint IRTAD/OISEVI Conference in Buenos Aires. The meeting agreed on 12 recommendations on better safety data for better road safety outcomes, including that:

Full details can be found at the following website: http://www.internationaltransportforum.org/jtrc/safety/Buenos-Aires-Declaration.html

In Europe, a centralised database of road crashes has been developed. The Community Road Accident Database (or CARE) is hosted by the European Commission and includes information on fatal and injury crashes. Details on individual crashes are retained (i.e. the information is not combined), thereby allowing for more powerful analyses to be conducted. A protocol for the collection of data has been developed, with common variables specified. The intention of the database is to provide the basis for analysis to:

Further information on CARE can be found on the European Commission website (http://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/index_en.htm).

The integration of safety data provides a large number of benefits, including:

In addition, linked data can be used to validate other sources of information. As an example, crash database systems can either draw information directly from asset data to provide additional information on road elements, or this linkage can be used to reduce the likelihood that data entry errors will occur by validating the presence of different road features or assets. It can also be used for research on specific topics.

Key linkages include combining crash data with:

The linkage process involves several stages, and can be temporary (e.g. for a specific project or policy need) or permanent (e.g. for ongoing analysis and monitoring). Data needs to be collected in a format to facilitate linkage. This typically involves provision of a common data element, most usefully the spatial coordinates for road based elements (including crashes), while for non-spatial data, another unique identifier will be required for the datasets to be linked. A comprehensive safety information system may have a large number of component files.

Once the data has been linked, it can be analysed through merging of data files. For spatial data, a GIS software package is able to assist greatly in this task, and is particularly useful for mapping information from different sources.

Once the initial investment in collecting data has been made, it may be a relatively low cost task to join different sources of information together to meet a variety of needs, especially if a unique identifier has been used in each dataset. In other circumstances, especially where data is not in a compatible format, the task might be quite substantial involving considerable investment.

One of the more commonly used linkages is the calculation of crash rates to allow either benchmarking or identification of high risk locations. For example, crash data can be combined with population figures, traffic volumes, or vehicle registrations to provide a useful comparison of risk. Ideally, each of these would be presented as fatal and serious injury crash rates. Each of these measures is useful for different purposes, as outlined below:

Crash data can also be combined with road inventory data. At a simple level, this can provide information about current road features that may be present, providing information about possible infrastructure safety improvements. For example, crash data of run-off-road crashes could be presented alongside information on current roadside barrier locations on a map to allow for a quick visual analysis of locations that might benefit from further barrier installation.

Combining data on crashes with roadway, asset, environment, and traffic volume data can lead to some important outcomes relating to safety performance of infrastructure. It is possible to compare the safety performance of different types of infrastructure for different traffic volumes. For example, the performance of divided and undivided roads can be compared for different traffic volumes. In addition, crash performance of different infrastructure can be compared at different levels of traffic volume, for different road user types, or for different environment types (e.g. low versus high speed environments). Box 5.9 provides information on the US Highway Safety Information System.

A large number of studies have been conducted using this rich source of information. This has led to the production of various research reports, summaries and tools. Recent examples include a study that examined the safety effects of horizontal curves and grades on rural two-lane highways; a safety evaluation of lane and shoulder width combinations; an evaluation of the safety benefits of transverse rumble strips on approaches to stop-controlled intersections in rural areas; and a review of the safety benefits of ‘road diets’ (converting four lane arterial roads to two lanes, plus a central two-way turn lane).

Further information on the HSIS can be found at the following website: www.hsisinfo.org

Recent initiatives in integration have involved the combination of crash data and road risk assessment data. This provides a very powerful tool for identifying risk locations and possible solutions. Further information on the combination of this data can be found in Combining Crash Data and Road Data and Intervention Selection and Prioritisation.

The Denmark case study shows how data can be integrated to create a more accurate picture of contributing factors to crashes.

Austroads, (2005), Australasian road safety handbook volume 3, Why we continue to under-count the road toll, Austroads, Sydney, Australia.

DETR (2001), A road safety good practice guide for highway authorities, DETR, London, United Kingdom.

Global Road Safety Facility GRSF (2009), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility World Bank, Washington DC.

Global Road Safety Facility GRSF (2013), Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, Global Road Safety Facility, World Bank, Washington, DC.

GRSP (2006), Helmets: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2007), Drinking and driving: a Road Safety Manual for Decision-makers and Practitioners, Global Road Safety Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2008), Speed management: a Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners, GRSP, Geneva, Switzerland.

GRSP (2009), Seat-belts and child restraints: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, FIA Foundation for the Automobile and Society, London, United Kingdom.

IRTAD, (2011), Reporting on serious road traffic casualties: combining and using different data sources to improve understanding of non-fatal road traffic crashes, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris, France.

Mansfield, H Bunting, A, Martens, M & van der Horst, R (2008), Analysis of the On-the-Spot (OTS) road accident database. Road Safety Research Report 80, Department for Transport, London, United Kingdom.

OECD (2007), IRTAD special report: Underreporting of road traffic casualties, OECD, Paris. France.

OECD/ITF (2014) IRTAD Road Safety Annual Report 2014, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris, France.

Ruengsorn, D, Chadbunchachai, W, & Tanaboriboon, Y, (2001), Development of a GIS based Accident Database through trauma management system: the developing countries experiences, a case study of Khon Kaen, Thailand, Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, 4, 5, 293-308.

Thomas, P, Muhlrad, N, Hill, J, Yannis, G, Dupont, E, Martensen, H, Hermitte, T, Bos, N (2013) Final Project Report, Deliverable 0.1 of the EC FP7 project DaCoTA.

Turner, B & Hore-Lacy, W, (2010), Road safety engineering risk assessment part 3: review of best practice in road crash database and analysis system design, Austroads, Sydney, Australia.

United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC), (2011), Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011 – 2020, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Ward, H Lyons, R Thoreau, R (2006) Under-reporting of road casualties: phase I. Road Safety Research Report 69, Department for Transport, London, United Kingdom.

WHO (2010), Data systems: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

WHO, (2013), Global Status Report on Road Safety 2013, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.