Part II "Road Safety Management" presents strategies for delivering targeted improvements and detailed guidance on how to plan, design, prioritize, implement, and manage these interventions within a country’s road network

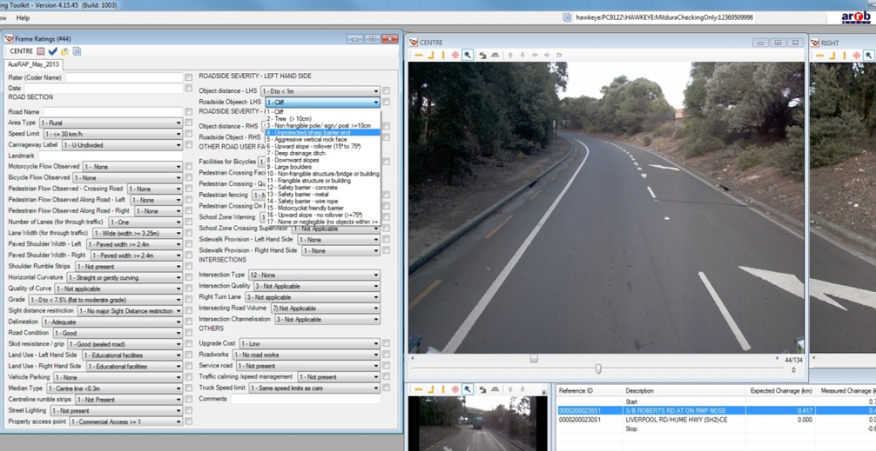

© ARRB Group

Road safety management is the first and fundamental pillar of the Decade of Action’s Global Plan (UNRSC, 2011) and the Global status report on road safety 2015 (WHO, 2015) and remains critical for successful implementation of the Global Plan for 2021-2030 (UNRSC, 2021). The Decade of Action and the Global Plan emphasise that improving road safety performance requires a systematic and planned approach. Establishing an effective road safety management system is the means by which countries and organisations can achieve this.

This chapter serves as a brief introduction to the key elements of effective road safety management system frameworks and new tools. The aim is to outline the general scope of understanding of the road safety management task to provide background and context for more specific guidance that follows throughout this manual.

The chapter highlights the importance of institutional management at all levels to provide the foundation for successful road safety intervention and sustainable results. It emphasises the overarching importance of governmental leadership at the country level and top management leadership of road safety in organisations. New tools are presented which are designed to help countries and organisations develop or improve their road safety management systems. Practical next steps which countries can take towards these ends are briefly outlined and are developed further in subsequent chapters.

LMICs need to work actively to establish and develop their road safety management systems to address challenging road safety problems in a systematic way.

All countries need to review their performance and benchmark it against effective practice before developing new road safety strategies and plans and projects.

All countries should consider adopting the long-term Safe System goal, set interim targets (initially at project level for LMICs) and move to implement effective measures towards its delivery for example, using funded demonstration projects to build new capacity. All countries should target high concentrations of fatal and serious injuries on sections and areas of the road network where the biggest gains can be made.

New review tools, international professional networks and international development aid can help LMICs get started. Technical assistance in crash database development, infrastructure safety improvements, and general deterrence-based road safety enforcement programmes can be provided by the International Road Traffic Accident Database Group (IRTAD), the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP), and the International Road Policing Organization (RoadPOL), respectively.

This section presents a brief summary of road safety management system frameworks and related tools for jurisdictions and organisations. The user of this manual is encouraged to consult original sources and the links to detailed information about road safety management frameworks, tools and their use, which are provided throughout the section.

Countries with the safest road networks demonstrate many common characteristics in their management of road safety. They have targeted better safety outcomes, adopted a systematic approach to intervention, and put in place a range of institutional arrangements which have been built up over many years (OECD, 2008; GRSF, 2009, 2013).

For more information:

These tools are designed to assist decision-makers and practitioners anywhere in the world in developing sustainable management systems. They outline pragmatic steps to build initial capacity to achieve road safety results. These tools are designed to be mutually reinforcing. They provide guidance on accountable, results-focused institutional management; promote the adoption of the Safe System goal and approach with interim targets and encourage implementation of demonstrably effective interventions to address known risk factors associated with death and serious injury in road crashes.

The main focus of this section is the country or jurisdictional road safety management system. A brief outline of the international standard for organisations is given in Institutional Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools.

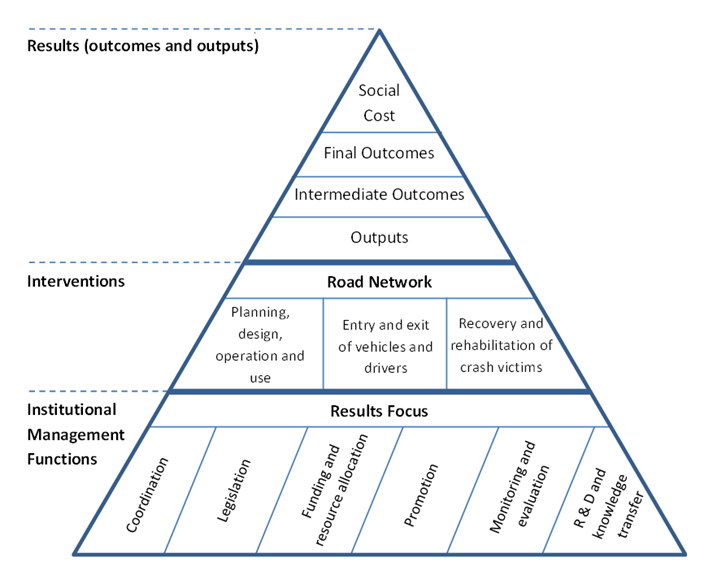

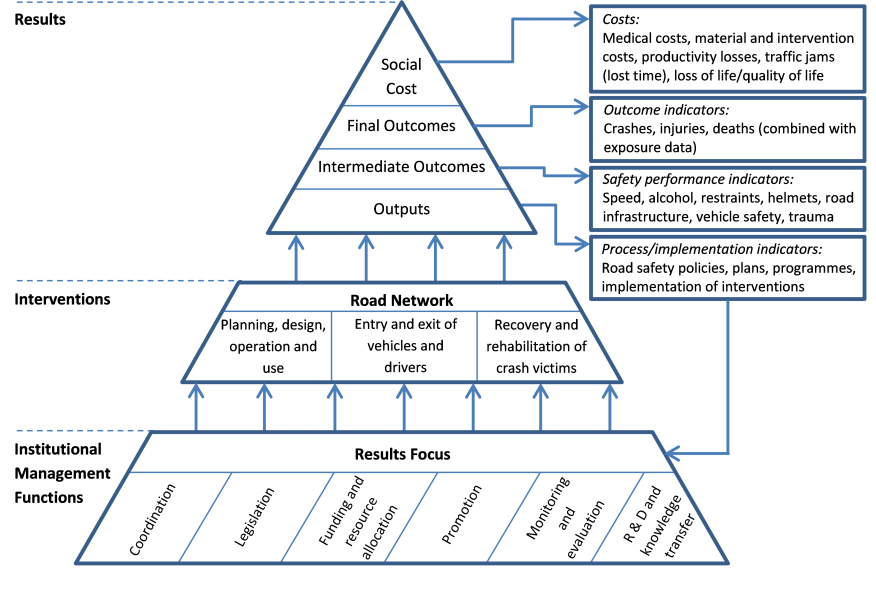

A road safety management assessment framework has been developed based on effective practice which identifies those elements of management that are crucial to improving country/jurisdictional road safety performance (GRSF, 2009; 2013). Safety is produced just like other goods and services and the production process in the framework illustrated in Figure 3.1, is viewed as a management system with three levels: institutional management functions produce interventions, which in turn produce desired results.

Figure 3.1 The road safety management system

The following sections provide a brief description of the three management system elements shown in Figure 3.1.

The foundation of an effective country road safety management system is institutional management, as indicated in the bottom level of the pyramid shown above. Key elements of effective institutional management have been identified and defined through global study of management systems and leadership arrangements in countries and jurisdictions that have achieved substantial reductions in deaths and serious injuries (as well as those in countries without such arrangements and which have been less effective) (OECD, 2008; GRSF, 2009; 2013, GRSF 2006–09, ITF 2016). These are outlined in Box 3.1.

Source: GRSF, (2009).

The overarching function and the rationale for the management system is to reduce crashes leading to fatal and serious injuries (results focus). This represents the expression of a country or jurisdiction’s desire to achieve better road safety results through performance review; analysis of the scope for crash reduction efforts, setting long-term goals and interim targets for road safety strategies, programmes and projects and providing the means and accountabilities needed to achieve them. The delivery of this function is discussed fully in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects. Supporting this key function are defined arrangements and capacity for coordination, legislation, funding and resource allocation; promotion; monitoring, analysis and evaluation, research and innovation, knowledge development and transfer. In the absence of a clear and accountable focus on fatal and serious crash reduction, all other institutional management functions and interventions lack cohesion and direction, and the efficiency and effectiveness of safety initiatives can be undermined (GRSF, 2009; 2013). For these reasons and as advised in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects, LMICs should exercise caution in establishing complex targeted strategies and plans until data and appropriate management capacity are available. However, measurement of safety performance and targeting specific results is recommended in funded, ‘learning by doing’ demonstration corridor/area projects.

Institutional management functions are delivered primarily by the government agencies with core road safety responsibilities – e.g. transport, land-use planning, roads, justice, police, health, occupational health and safety and education. They are also delivered in government partnerships with civil society and business, in alignment with country and organisational goals and targets. The professional and research community provide key support for demonstrably effective next steps. As highlighted previously, governmental leadership and the setting up of a governmental lead agency are prerequisites for successful activity (Peden et al., 2004; OECD, 2008, GRSF, 2009, 2013).

Institutional management functions and examples of their delivery are referred to throughout this manual. A range of in-depth case studies which illustrate successful country delivery can be found in Annex 2 and Annex 4 of the road safety management guidelines produced and used by the World Bank (GRSF 2009).Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies Plans and Projects as well as Annex 3 and Annex 4 of global road safety management guidance (GRSF 2009, 2013) provide guidance on establishing or strengthening lead agency arrangements.

The second element of the road safety management system framework outlined in Figure 3.1 is system-wide intervention. Effective intervention focuses on the implementation of evidence based approaches to reduce exposure to the risk of death and serious injury; to prevent death and serious injury; to mitigate the severity of injury when a crash occurs, and to reduce the consequences of injury. Interventions need to address the safety of all users and take future demographics into account, notably the physical vulnerability of very young and of the ageing society.

A common misperception in countries getting started in road safety is to assume that since 90% of crashes may be due to human error, then direct approaches relying heavily upon education and training play a substantial part in saving lives and preventing serious injuries. Although these measures play a supportive role, there is little evidence to confirm that education and training, alone, will achieve road safety results. Speed management, the safety engineering of vehicles and roads and improvements in the emergency medical system response are observed to play the major role (Peden et al., 2004). At the same time, the Safe System goal requires the examination of contributory factors in road safety engineering and other interventions to shift from a focus on crash prevention to a focus on death and serious injury prevention. Again, research on contributory factors to deaths and serious injuries indicates that intervention to improve speed management and the intrinsic safety of vehicles and the road environment all have a major role to play in addressing this new focus (Stigson et al., 2011).

The Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) has developed an evidence-based guide on "what works and what does not work" when selecting and applying road safety interventions that are effective in reducing fatal and serious injuries (Turner et.al., 2021). The guide highlights that not all road safety interventions are equally effective and that what appear to be "common-sense" interventions will often not be the best, and in some cases may have very limited or even negative impacts, despite being commonly - and mistakenly recommended or accepted. The guide sets out evidence and presents case studies on interventions within a Safe System context and with a focus on LMICs, although the information presented is of relevance to all countries.

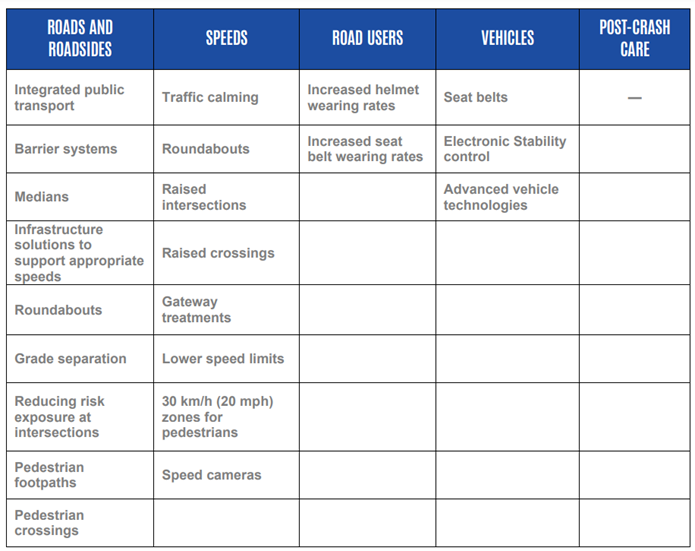

Better performing countries implement integrated packages of road safety interventions that have demonstrated significant performance gains as well as implementing innovation based on established safety principles. The findings of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention provide a substantial consensus-based blueprint for country, regional and global action, and have subsequently been endorsed by successive United Nations General Assembly resolutions (Peden et al., 2004). Reports by the OECD, ITF and World Bank (e.g., OECD, 2008; ITF, 2016; Turner et. al., 2021) also provide international reviews on the effectiveness of interventions. Information is also available from the SUNflower study (Koornstra et al., 2002), the European Road Safety Observatory (2014) and guidance produced by the UNRSC (2006–13). Key recommended intervention strategies include:

Examples of highly effective road safety interventions within a Safe System context are highlighted in Box 3.2.

Highly effective countermeasures

This manual is intended to provide clear and accessible information on the effective management of road safety infrastructure with a focus on the selection and application of road infrastructure interventions. To produce rapid results, road safety programmes must initially target high concentrations of crash deaths and serious injuries on sections of the road network where the biggest gains can be made.

The planning, design, operation and use of the road network is generally called road infrastructure safety management (RISM) as described in the 2008 EU directive (and as outlined in Part 3 of this manual). The products and services used within RISM address the conditions under which vehicles and road users can safely use the road network combined with the safe recovery and rehabilitation of crash victims. In all these areas, specific standards, rules, guidelines, policies and protocols are set with compliance and oversight mechanisms in place

This manual does not set out to provide detailed guidance on road safety intervention in general but relates specifically to the planning, design, operation and use of the road network within the context of the RISM process.. See Part 3 Chapter 9 Infrastructure Safety Management and Chapter 10 Risk and Issue Identification for information on the RISM process including approaches to infrastructure safety management and assessing road network risks, respectively. Then, see Chapter 11, Intervention Selection and Prioritisation for guidance on intervention selection and prioritisation to address these risks. Here, cross references are also made to key work carried out by PIARC which includes its recent work and guidance on road hierarchies which provide a fundamental framework for safety management of the road network.

The final element of the road safety management system shown in Figure 3.1 concerns the measurement of results and their expression as targets in terms of final outcomes, intermediate outcomes, and outputs (Bliss, 2004). Targets define the desired safety performance endorsed by government at all levels, stakeholders and the community. The level of safety is ultimately determined by the quality of interventions that have been implemented, which in turn are determined by the quality of the country’s delivery of institutional management functions. The GSRF highlighted a few examples of success in Leveraging Global Road Safety Successes (2016)

Final outcomes can be expressed as a long-term goal for the future safety of the road traffic system (e.g. as in Safe System, Vision Zero) and interim, short- to medium-term targets towards this expressed in terms of social costs, fatalities and serious injuries usually presented in absolute terms. They can also be measured and targeted in terms of rates per capita, vehicle, and volume of travel. See IRTAD (2014) for further discussion.

Intermediate outcomes are linked to improvements in the final outcomes and typical measures include average traffic speeds, the proportion of drunk drivers in fatal and serious injury crashes, seatbelt-wearing rates, helmet-wearing rates, the physical condition or safety rating of the road network (e.g. iRAP ratings), the standard or safety rating of the vehicle fleet (e.g. Global NCAP ratings), and emergency medical system response. See ITF (2016) for further discussion on intermediate safety performance indicators.

Outputs represent physical deliverables that underpin improvements in intermediate and final outcomes. Examples are kilometres of safety engineering improvements implemented and the number of police enforcement operations required to reduce average traffic speeds, increase seatbelt use or reduce drinking and driving. They can also correspond to milestones showing a specific task has been completed (Bliss, 2004).

Countries active in road safety are increasingly setting measurable final outcome and intermediate outcome targets. In some cases, they also set related measurable output targets in line with the targeted outcomes. As mentioned previously, in many LMICs, where capacity to implement national targeted plans is non-existent or in a fledgling state, countries are advised to adopt the long term Safe System goal but to restrict the setting of quantitative targets to funded corridor and area demonstration projects. Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies, Plans and Projects provides guidance on road data systems, which allow the setting and monitoring of targets. Case studies are presented in Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes of target-setting in different contexts. See Part 3 Chapter 12 for guidance on Monitoring, Analysis and Evaluation of Road Safety Interventions.

All three elements of the road safety management system – institutional management functions, interventions and results – need to be benchmarked against identified effective practice as countries develop new projects, programmes and strategies, regardless of their stage of development (OECD, 2008). Institutional Management Functions in Management System Framework and Tools outlines recommended steps and available tools to assess the strengths and weaknesses of country road safety management and to implement necessary capacity building initiatives.

Guidance has been published by the World Bank to assist countries which want to improve their road safety outcomes (GRSF, 2009, 2015). These acknowledge that building effective capacity requires long-term investment and will not be achieved overnight. These address the central issue of how to shift from weaker to stronger institutional management to make this happen. The guidance outlines two practical steps to strengthen country road safety management. The first step, noted below, comprises a road safety management capacity review which helps to identify strengths and weaknesses in current approaches.

The recommended first step for countries is to carry out a road safety management capacity review. Road safety management capacity review has been independently evaluated as a cost effective, good practice tool that has been used widely in LMICs. It has also been used in Sweden and Western Australia where it has contributed to strengthening in some aspects of institutional delivery to good effect (GRSF, 2012).

Capacity review objectives: The aims of the capacity review are to:

Road safety management capacity review involves engagement with senior management in key government agencies and the private sector who are able to influence country results. The review is conducted by experienced, internationally recognised, external road safety specialists with senior management experience at country and international levels.

Capacity review steps: A country capacity review is conducted through nine distinctive steps:

Twelve checklists are used to help assess and benchmark all elements of the management system and their linkages according to effective practice (see GRSF, 2009, 2015).

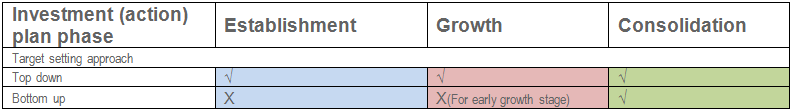

Long-term investment strategy: On the basis of the review, a long-term investment strategy is developed which lays a pathway from weak to strong capacity via establishment, growth and consolidation phases of the investment strategy. These phases are discussed fully in Targets and Strategic Plans.

The first stepping stone for many LMICs in establishing their road safety activity will be to prepare road safety projects rather than embark initially on the ambitious national road safety plans foreseen in the growth phase. Road safety management capacity reviews indicate that LMICs that specify national plans without the funded capacity to achieve them are unsuccessful (GRSF, 2006–13). The practical aim is to deliver key capacity building elements in funded implementation projects, such as those outlined in Section 3.4 in the establishment phase of the investment strategy.

The project involves building core institutional capacity to measure and target safety outcomes in high-volume, high-risk corridors and areas, with specific attention being paid simultaneously to lead agency and related coordination arrangements and monitoring and evaluation. This provides a basis for the scaling up of investment to accelerate this capacity strengthening, and the achievement of improved results across the road network in a national plan for the growth phase.

The second step of the country guidance is the careful preparation and implementation of Safe System road safety projects to deliver the establishment phase of the investment strategy (GRSF, 2009; 2015). As mentioned previously, carefully prepared and funded demonstration corridor projects provide an excellent means for countries starting out in road safety or countries embarking on more ambitious approaches to build initial capacity.

Current World Bank road safety investment in capacity building efforts is focusing on systematic, measurable and accountable investment programmes. These simultaneously advance the transfer of road safety knowledge, strengthen the capacity of participating governmental partners and stakeholders, and rapidly produce results in targeted high-risk corridors and areas. The aim is to provide benchmarks, dimensions and capacity for the next stage of investment (GRSF, 2013). Recommended project components are briefly outlined in the ‘Getting Started’ material at the end of this chapter, while examples are provided in Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes. Complementary guidance has been issued for a streamlined approach to capacity review and project development and ‘mainstreaming’ road safety in regional trade road corridors (GRSF, 2013; Breen et al., 2013).

While the two-step process outlined above has been identified to inform investment priorities in LMICs, the above tools have also been used by HICs which have moved to a Safe System approach (Breen et al., 2008; Howard et al., 2010). Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes provides examples of capacity building demonstration projects that can help build leadership and coordination arrangements, implement multi-sectoral action, and achieve quick results in targeted high-volume, high-risk corridors and areas.

This section has briefly introduced capacity building tools. The main principles which underpin this guidance can be summarised as: the need to address all elements of the road safety management system in reviewing management capacity to produce results; adoption of a phased approach to road safety investment and a ‘learning by doing’ approach; targeting the highest concentrations of deaths and serious injuries across the road network and adopting a Safe System approach; and building global, regional and country road safety management capacity. Practical examples of how these tools are being used worldwide are presented throughout this manual. Readers are referred to the original guidance for a detailed discussion (GRSF, 2009, 2015).

© ARRB Group

Motor vehicle crashes are a leading cause of death and long-term injury at work and in driving associated with work. For example, surveys in several EU countries indicate that between 40–60% of all work accidents resulting in death are road crashes. Studies conducted across the world indicate that the costs of work-related crashes are substantial, both for society and employers (DaCoTA, 2012b). ). To reduce death and serious injury the International Standards Organization developed ISO 39001: Road Traffic Safety Management Systems: Requirements with guidance for use standard has been produced.

The standard is designed to assist organisations in integrating road safety as a core objective into their management systems, as well as aligning with country road safety goals and strategies. The standard is aimed at both small and large organisations, as well as the public and private sector Specific examples given include organisations concerned with transporting goods and people; those generating traffic, such as schools and supermarkets; and those responsible for provision of the road network.

The ISO 39001 standard links to other ISO management systems standards and sets out specific and wide-ranging top management responsibilities and key management functions. ISO 39001 requires organisations to adopt the Safe System goal and to make decisions on objectives and targets for the interim as well as plans to achieve them. The organisation is required to follow a process that starts with a review of its current road traffic safety performance; makes an assessment of the context for the organisation’s activity; and considers specified, measurable road traffic safety performance factors known to reduce the risk of fatal and serious injury within the organisation's sphere of influence. The organisation has to select the road traffic safety performance factors to work on and then analyse what it can achieve over time. When establishing its targets, the organisation is required to consider the management capacity required to achieve them, as well as monitoring results and reviewing its road safety management system towards continual improvement (ISO, 2012).

Early adopters of ISO 39001 include freight and passenger transport organisations and companies in Sweden and Japan. If implemented within the national policy framework, the tool has high potential to engage employers of organisations of all sizes in effective road safety activity. In the case of LMICs, early adoption of ISO 39001 by large corporations in the first instance could assist governments in meeting their serious road safety challenges.

When the main objective is to avoid accidents on the roads, all levels of society need to make a contribution. At the highest level, the way in which society decides on its transport needs, the choice of transport and mobility, the level of provided transport equipment and facilities, the level of education of road users, etc., are all influenced. All these factors, which are controlled at the national and to some extent global level, are also of great importance for the level of road safety at the local level. However, they cannot be directly influenced by individual municipalities.

At a lower level, road safety is also the result of practical planning, in other words, where activities are located and how the transport system is structured. For example, the road and street system can be divided into different categories according to the activities and potential disturbances. A certain level of traffic safety required by one group of road users often contrasts with the level of safety desire by another. How different modes of transport look and how conflicts between them are prioritised is very important in determining the risks to which different groups of transport users are exposed. Longer journeys expose more people to more risks and generally lead to more accidents. Municipalities have the opportunity to influence this through sound planning. It is also needed to create good operating conditions for public transport which reduces crash exposure through the reduction of vehicle volumes.

Road safety can be examined in more detail by looking at the behaviour of road users and how they use and take or reduce risk behaviours on the transport system. The transport environment places demands on the behaviour of road users, and the capacity of road users places demands on the design of the surrounding environment as it interacts with road users and how road users interact with each other can help to understand the causes of individual accidents. It is the responsibility of the municipal system and to maintain the quality level. In this respect local influence is strong.

The design and planning of the municipal transport system therefore directly affects future road safety, but it is important to understand that municipal planning also affects the level of road safety in the municipality well into the future. This is why road safety must be integrated into all planning of the physical environment.

In the context of extended social planning, road safety is one of many factors influencing other aspects. Other aspects also influence road safety. Balanced weighting between different attributes such as urban character, accessibility, safety, road safety and environmental impact will ensure a sustainable outcome in the long term. Features can work for or against each other and can also compete for available resources. Therefore, municipalities need to make their own priorities and adjust their investments according to their needs and resources.

Road safety affects urban space and urban life appropriate speed and well-designed urban space have synergetic effects. Road Safety can act as a catalyst for creating a more beautiful urban space and a safer more vibrant city. Improved road safety can also have positive effects on noise and air quality. More moderate speeds reduce emissions and noise. Lower speeds also reduce the attractiveness of car traffic, which reduces the flow car traffic to some extent.

Success in local road safety work requires the creation of structures and the acquisition of information involving several municipal functions. Different measures need to be prioritised and the most cost-effective ones selected for implementation Intervention and Prioritisation. There is a need to create continuity in the work and for municipal officials, politicians and, above all, the general public to learn to understand the problems better. To this end, a road safety programme must be drawn up, documenting the objectives and the efforts to be made, and to which a commitment must be made, and to which a commitment must be made. It will be easy to monitor progress (see monitoring and evaluation) and new programmes can be drawn up at the end of the programme period. A systematic approach is the basis not only for success but also for increasing knowledge in society a. A systematic approach requires clear objectives, knowledge of the current situation and a clear understanding of how to achieve them.

Bliss T (2004), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, Transport Note No. TN-1, World Bank, Washington DC.

Breen J, Howard E, & Bliss T (2008), Independent Review of Road Safety in Sweden, Swedish Roads Administration, Börlange.

Breen J, Humphreys RM & Melibaeva S (2013), Guidelines for Mainstreaming Road Safety on Regional Trade Road Corridors, SSATP, World Bank, Washington DC.

DaCoTA (2012a), Road Safety Management Deliverable 4.8d of the EC FP7 project DaCoTA, Brussels

DaCoTA (2012b), Work-related Road Safety Deliverable 4.8d of the EC FP7 project DaCoTA, Brussels

European Road Safety Observatory (2014), http://ec.europa.eu/transport/road_safety/specialist/knowledge/dacota/safety-issues/index_en.htm

EU Directive 2008/96/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on road infrastructure safety management

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) & World Bank (2006-2013), Unpublished country road safety management capacity reviews, Washington DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2009), Implementing the Recommendations of the World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Country guidelines for the Conduct of Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and the Specification of Lead Agency Reforms, Investment Strategies and Safe System Projects, by Bliss T & Breen J; World Bank Global Road Safety Facility, Washington DC.

Global Road Safety Facility GRSF (2012), MDB Staff Training Program: Module 7, African Development Bank, Tunis, Tunisia

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2013), Road Safety Management Capacity Reviews and Safe System Projects, by Bliss T & Breen J; World Bank, Washington, DC.

Global Road Safety Facility (GRSF) (2013), Leveraging Global Road Safety Successes, World Bank, Washington, DC.

International Standards Organisation ISO (2012), 39001: Road Traffic Safety (RTS) Management Systems – Requirements with Guidance for Use, Geneva.

International Traffic Safety Data and Analysis Group (IRTAD), Road Safety Annual Report 2014, International Transport Forum, Paris

ITF (2016), Zero Road Deaths and Serious Injuries: Leading a Paradigm Shift to a Safe System, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789282108055-en

Koornstra M, Lynam D, Nilsson G, Noordzij P, Pettersson HE, Wegman F & Wouters P (2002), SUNFlower: A comparative study of the development of road safety in Sweden, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, SWOV, Dutch Institute for Road Safety Research, Leidschendam. Available on the Internet: http://www.swov.nl/rapport/sunflower/sunflower.pdf

Land Transport Safety Authority (2000), Road Safety Strategy 2010: A Consultation Document. National Road Safety Committee, Land Transport Safety Authority, Wellington.

OECD (2008). Towards Zero: Achieving Ambitious Road Safety Targets through a Safe System Approach. OECD, Paris, see OECD 2008 for summary document.

Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, Mohan D, Hyder A, Jarawan E, Mathers C eds. (2004), World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, World Health Organization and World Bank (Washington), Geneva.

Stigson H, Kullgren A & Krafft M (2011), Use of Car Crashes Resulting in Injuries To Identify System Weaknesses, Paper presented at the 22nd International Technical Conference on the Enhanced Safety of Vehicles (ESV). Washington DC, USA. DOT/NHTSA

Turner, B., Job, S. and Mitra, S. (2021), Guide for Road Safety Interventions: Evidence of What Works and What Does Not Work. Washhington, DC., USA: World Bank

United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) (2011), Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011 – 2020, World Health Organization, Geneva.

United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) (2006-2013) See http://www.who.int/roadsafety/ for range of guidance produced.

United Nations Road Safety Collaboration (UNRSC) (2006-2013)

World Health Organization (WHO)(2021), Global Plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, World Health Organization, Geneva. status report on road safety 2013: supporting a decade of action, World Health Organization, Geneva.

Wegman F (2001), Transport safety performance indicators. Brussels, European Transport Safety Council.

This chapter outlines the Safe System approach from first principles to end delivery of safe outcomes, with cross-referencing to the detailed planning and design activities that give effect to a Safe System approach, which are set out in later sections of this manual.

A Safe System approach within the road transport system is built around the premise that death and injury are unacceptable and are avoidable. This approach seeks to ensure that no road user is subject to kinetic energy exchange in a crash which will result in death or serious long-term disabling injury. OECD (2016) endorses the Safe System approach and notes that Safe System principles represent a fundamental shift from traditional road safety thinking, reframing the way in which traffic safety is viewed and managed.

The Safe System represents a major change to past approaches. It overturns the fatalistic view that road traffic injury is the price to be paid for achieving mobility. It sets a goal of eliminating road crash fatalities and serious injuries in the long-term, with interim targets to be set in the years towards road death and serious injury elimination.

This elimination is feasible. It requires system reconfiguration and recognition that the network must eventually be forgiving of routine human (road user) errors. It is important to recognise the fundamental change that road safety agencies, including road authorities, will face in embracing and implementing this Safe System aspiration and in implementing Safe System treatments across their networks (See Responsibilities and Policy for road authority impacts).

ITF (2016) suggest that the key Safe System principles are that:

A video has been produced by the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) describing the Safe System approach, and the role of different parts of the system. This provides a very useful introduction to this topic (See The Difference Between Life and Death – a 20 minute film).

A commitment is needed from agencies to review their road safety capacity (see Safety Management System); to develop understanding of the principles of Safe System and its elements; to adopt a long term goal for elimination of fatalities and serious injuries.

Countries must develop their knowledge to address gaps within the agencies (and of other stakeholders) as to what a Safe System approach is and what practical change this will require in management and intervention approaches. Over time all Safe System elements (See Safe System Elements), and the safety of all road users are to be addressed. Funding needs are to be identified and advocated to government.

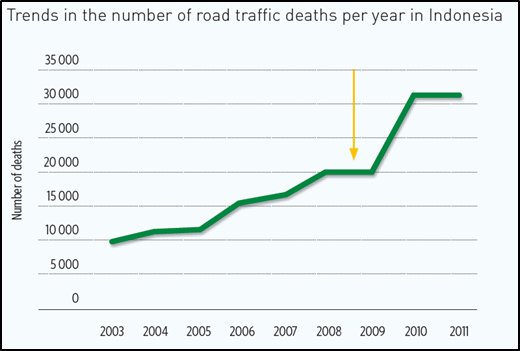

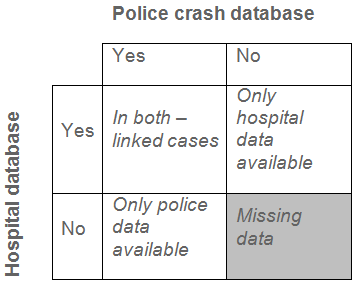

Understanding of major crash types (See Crash Causes) should be determined from crash data or if not available, by discussions with police and emergency services workers. Develop a reliable crash data system as soon as possible (See Safety Data).

Road assessment programmes can play a part in identifying higher risk sections of a network and in identifying affordable treatments, especially where reliable crash injury data is not available. Weaknesses in Safe System elements (roads and traffic management - including roadside management and abutting development access controls, see Section 7.3; vehicles, speeds; and road user behaviours) which contribute to fatalities and serious injuries in these crash types should be determined.

In the short term, for new road projects, adoption of Safe System design policies which apply Safe System principles to treatments to reduce fatal crash risk will be developed. Design guidelines would follow subsequently but these would be a substantial development task which requires an incremental medium-term approach.

Seek to improve user behaviour and compliance (See Safe System Principles) across the whole existing network through improved traffic management guidance, reduced speed limits in high risk areas and improved police enforcement, offence penalties and public education See Targets and Strategic Plans for the recommended demonstration project approach.

In the medium to longer term: Carry out progressive retrofitting of the existing system. Do what is feasible to improve infrastructure safety and further improve behaviour and compliance through licensing system reviews and legislative changes re offences. Continue public education campaigns and seek improved vehicle safety regulation and public education.

The Safe System approach is a comprehensive safety philosophy, developed and internationally agreed-upon to form the foundation for safe design and operation of the road transport system. The deficiencies in traditional approaches to achieving a safe road network were highlighted by Tingvall (2005). He noted that the road transport system internationally has traditionally been characterised as follows:

These comments draw attention to the fact that there has been a lack of acceptance of responsibility in this field by most governments. The safest communities (OECD, 2016) will be those that embrace the shift towards a Safe System and begin work now on the interventions required to close the gap between current performance and the performance associated with a genuinely safe road traffic system.

This requires understanding not only of the current system’s safety weaknesses, but also of what change may be possible in the short-term to achieve Safe System compliant outputs. Sufficient management leadership within government road safety agencies (including road authorities), as outlined in Chapter 3, The Road Safety Management System, is essential to achieve meaningful progress in the delivery of these substantially different outputs.

A Safe System will exist when road users are no longer exposed to death or serious injury on the network.

The Safe System approach focuses on eliminating crashes that result in fatal or serious injury outcomes; that is, those crashes that are a major threat to human health. It draws upon the Swedish Vision Zero and the Dutch Sustainable Safety road safety visions and objectives. Safe System Principles provides information on other key elements of the Swedish and Dutch approaches.

The Swedish Vision Zero asserts that human life and health are paramount (Tingvall, 2005) and no long-term trade-off is allowed, reflected in the ethical imperative that “It can never be acceptable that people are killed or seriously injured when moving within the road transport system”. Tingvall (2005) notes that traditionally, mobility has been regarded as a function of the road transport system for which safety is traded-off. However, Vision Zero turns this concept around and resets mobility as being a function of safety (See References(Scope of Road Safety Problem)). That is: no more mobility should be generated than that which is inherently safe for the system. This ethical dimension reflects the principles accepted for workplace safety, where the effectiveness of the working process cannot be traded-off for health risks. Norway (NPRA, 2006), in adopting the Vision Zero goal, has highlighted the ethical approach underpinning it, i.e. “Every human being is unique and irreplaceable and we cannot accept that between 200 and 300 persons lose their lives annually in traffic”. Sweden is looking beyond Vision Zero as well, and in November, 2017 introduced "Moving Beyond Zero." Moving Beyond Zero is a major rethink of the Vision Zero policy and introduces an active transport advocacy campaign.

The objective of the Netherlands Sustainable Safety approach (Wegman & Aarts, 2006) is to prevent road crashes from happening, and where this is not feasible, to reduce the incidence of (severe) injuries whenever possible.

OECD (2016) points out that while Vision Zero is based on an ethical principle to eliminate death and serious injury from the transport system, Sustainable Safety takes elimination of preventable accidents as the starting point and attaches greater weight to cost-effectiveness in determining interventions.

It is clear that this ethical position, which holds that the prime responsibility of a road authority is to support road users to reach the end of each of their trips safely, is being increasingly adopted by jurisdictions. The following literature supports the need for measures to save lives through achieving a ‘forgiving’ system:

The Safe System’s ethical goal of serious casualty elimination will not be achieved overnight. It requires a long-term timeframe for actions to be developed and implemented in successive intermediate timeframes, to deliver incremental serious casualty reductions (to meet interim targets over the medium-term) and support progress towards the long-term goal. The following case studies from Belize and China show two long-term approaches to reducing fatal and serious crashes.

It also requires commitment to interim step-wise targets, which gives prominence to the long-term goal (OECD, 2016; GRSF, 2009; 2012; Breen, 2012).

PIARC (2012), in its National Road Safety Policies and Plans Report, notes that best practice in target setting is represented by government commitment to a long-term goal of zero fatalities with strong interim targets that establish the path to success. Adoption of a long-term Safe System approach is identified good practice for managing for results and is supported by other key international road safety stakeholder organisations as outlined in Road Safety Management. Following the request of the United Nations General Assembly, on November 22, 2017, member states reached consensus on 12 global road safety performance targets. For more information see Developing Global Road Safety Targets. There is an increasing number of countries that have adopted a “Towards Zero” or fatal and serious injury elimination goal — the aspiration underpinning the Safe System approach. This long-term commitment to elimination of road crash fatalities and serious injuries at the highest level of government will influence and support road safety management and road safety policy in a jurisdiction and will be clearly reflected in the proposals described in a strategy and action plan to achieve ambitious interim targets. The following case study from the United States of America, discusses the Minnesota's Towards Zero Deaths initiative.

The safe system approach often requires road agencies to rethink their approach to how projects and programmes are implemented. It is important to begin with some understanding of the how the system is currently operating through objective performance measurement. The first case study discusses the Road Safety Manual which was developed to help the practitioner on the Safe System journey. Some nations have also started the journey through the "Star Rating" system developed as part of iRAP. This is shown in the second case study.

Brussels, Belgium (Source: J. Milton)

The Safe System approach provides a different way to look at crash causation, and at the key crash types that contribute to fatal and serious injury.

The traditional understanding of crash causation supported the perception that the driver or other road user error was the cause of most crashes and was therefore the major issue that needed to be addressed. While road user error is a contributing factor to many crashes, there are a number of key research findings that challenge the traditional allocation of most causation to driver/rider error (human behaviour) and the associated notion that human behaviour can easily be altered (also See the discussion in Designing for Road Users on this issue).

Kimber (2003) suggests past post-crash assessments of crash contribution by researchers resulted in too great a focus on driver behaviour at the time the data was collected. Interventions with potentially greater effect were easily overlooked. Driver behaviour is a wide category and it was easy to populate it by default when the evidence was incomplete or a better explanation was not available. Due to this perceived driver failure predominance, the main priority for many years was to concentrate on measures to change driver behaviour (rather than focusing on reengineering other parts of the road, vehicle or driver system) to eliminate the failures.

This mindset is changing, but the misguided focus on the significance of driver error still remains predominant in too much of the thinking across international communities.

Human error is to be expected. It is unhelpful to regard all human error as being capable of somehow being eliminated and the consequences of it therefore being avoided. When the circumstances of road and vehicle allow, routine driver errors translate into collisions, sometimes with injury or death resulting. A focus on the infrastructure and vehicle safety levels that interact with routine driver error is a much more useful means of identifying actions to reduce serious casualty outcomes.

Elvik and Vaa, (2004) indicate that, even if all road users complied with all road rules, fatalities would only fall by around 60% and injuries by 40%. Specifically, they note that around 37% of fatalities and 63% of serious injuries do not involve non-compliance with road rules. This indicates that routine human error leading to crashes, rather than deliberate or unintentional breaking of road rules, is a feature of human existence and road use.

While achieving compliance with road rules by road users remains critically important, this approach alone will not achieve the desired road safety gains in any country.

As practitioners from LMICs recognise, there is often a lower level of compliance with road rules and a lesser respect for the rule of law in most LMICs than for many HICs. This deliberate reluctance to act in accordance with the law would affect fatality and serious injury rates in these countries and this is one key difference in comparison to serious crash experience in many HICs.

While a substantial potential benefit is available in the medium term through changing this illegal road user behaviour in LMICs, a further focus upon improvements in infrastructure and vehicle safety over the medium to longer term will be essential in providing a forgiving system (a Safe System) for crashes arising from underlying (and not illegal) human error, as is the current and strengthening focus in many HICs. Therefore, research findings from HICs about the role of safer roads and vehicles are very relevant to LMICs.

Stigson (2011) conducted further analysis on the different weaknesses in the traffic system’s traditional components and determined that they play a greater or lesser role in influencing the outcome of crashes. The analysis confirms the potential for road infrastructure to more substantially impact upon fatal crash outcomes for car occupants than other factors in HICs.

While system weaknesses should usefully be analysed for two wheeler, cyclists and pedestrians in HICs and also in LMICs, vehicle safety improvement (as users shift over the next decades from two wheelers to vehicles) and improved behavioural compliance will offer great opportunities for reducing crashes in most LMICs compared to most HICs. However, the potential contribution of safer infrastructure to substantially reduce fatalities should be reinforced with all road authorities.

The movement to a focus on fatal and serious casualty injury reduction through the Safe System approach (as opposed to casualty crash reduction) has had a profound impact on the understanding of key crash types.

The shift in focus from crash numbers to casualties has a subtle but important impact on crash assessment and the strategies to address risk. Different types of crashes will produce different crash outcomes, including greater or lesser numbers of injuries per crash. For example, analysis from New Zealand on crashes and casualties demonstrates this point. Table (NZTA, 2011) shows the proportions of the three most common types of crashes and casualties that result in fatalities and serious injuries for rural roads (excluding motorways).

| Key crash types | % of high severity crashes on New Zealand rural roads | % of high severity casualties on New Zealand rural roads |

|---|---|---|

Run-off-road | 56% | 51% |

Head-on | 19% | 25% |

At intersections | 16% | 16% |

The table shows that 92% of fatal and serious injuries on rural roads in New Zealand are attributed to three key crash types. The table also shows that a higher proportion (1.30 to 1) of severe casualties (fatal and serious injuries) occur through head-on crashes (25%) than is reflected in the proportion of severe head on crashes (19%). This indicates that the head-on crash type is of greater significance for overall fatalities than the severe crash numbers would indicate.

Similarly, analysis of crashes by fatal and serious injury (compared to all injuries) is likely to provide a different picture of the risk across the network.

The relative incidence of various fatal and serious crash types will differ from most HICs to most LMICs due to the differences in traffic environments. The types of vehicles and their relative share of the overall traffic volume are two examples of likely difference. It is essential for the road safety agencies and road authorities to know what the major crash types are in their country and where they are occurring (also see Roles, Responsibilities, Policy Development and Programmes and Assessing Potential Risks and Identifying Issues). Agencies should be in a position to identify the higher fatal and serious injury crash risk lengths of roads on their networks.

The predominant road crash types that result in deaths and serious injuries in high-income countries are typically:

For many low- and middle-income countries, key crash types include:

The case study from India discusses the implementation of a speed regulation system.

CASE STUDY - India: Implementation of speed regulation system on highway A10

An innovation in engineering design practice was piloted in India on the Kamataka State Highway Improvement Project (550km). The project demonstrated how the iRAP Star Rating protocol can be used to rate the safety of a road prior to construction or rehabilitation with information drawn from the road design plans. Final designs for construction are anticipated to provide a reduction in severe injuries of 45% in India. Read more (PDF, 860 kb)

The Safe System approach places requirements on the road safety management system. These requirements include:

The system will ultimately need to protect all road users, including those who act illegally, from death and serious injury. In the interim period the focus should be on protecting those who do not act illegally and those who could be killed or seriously injured by the illegal actions or errors of other road users.

As noted above, as well as road user behaviour, road- and vehicle-related safety factors play a substantial part in fatal injury crashes. Progressive movement towards a Safe System requires all key stakeholders to accept their responsibilities to provide for safe overall operation of the network. This is in addition to the responsibilities that individual road users bear. This concept of ‘shared responsibility’ is at the core of the shift in traditional thinking about road crash contributing factors that a Safe System requires.

The Safe System approach looks to infrastructure design, speed limits and vehicle safety features that individually (and together) minimise violent crash forces. It relies upon adequate education, legislation and enforcement efforts to gain high levels of road user compliance with road rules; effective licensing regimes to control the safety of drivers using the system (particularly novice drivers and riders); and the cancelation of licences when serious offences are committed. A good standard of emergency post-crash care is also needed.

This fundamental shift away from a “blame the road user” focus, to an approach that compels system providers or designers to provide an intrinsically safe traffic environment, is recognised as the key to achieving ambitious road safety outcomes (OECD, 2016).

While individual road users are expected to be alert and to comply with all road rules, the ‘system providers’ — including the government and industry organisations that design, build, maintain and regulate roads and vehicles — have a primary responsibility to provide a safe operating environment for road users (See Box 4.1). This requires recognition of the many other system providers (beyond the road engineers and vehicle suppliers) who impact on use of the network and who also carry a major responsibility for supporting achievement of safer, survivable outcomes.

The studies noted in Crash Causes confirm the fundamental importance of those responsible for delivering safer roads and roadsides, safer travel speeds and safer vehicles, as well as safer behaviours. Road users should not have to operate in a system full of flawed designs that increase the probability of error. Sweden’s Vision Zero “envisages a chain of responsibility that both begins and ends with the system designers (i.e. providers)”. The responsibility chain (Tingvall, 2005) has three steps:

Many challenges are involved in monitoring ongoing performance of the responsibilities of system providers or system designers. They need to accept accountability for their outputs.

While the principle of shared responsibility has been naturally accepted in the road safety strategies of those countries who have adopted the Safe System approach, the necessary substantial (and often subtle) adjustment required to become accepted operating practice will take some time to achieve across agencies (including road authorities).

Road safety responsibilities also extend to the broader community. For example, health professionals have a role in helping their clients to manage their safety on the roads; and parents contribute significantly to the road safety education of their children — not only through their direct supervision of learner drivers, but also as role models through their own driving and road user behaviour. The Danish Road Safety Accident Investigation Board case study provides an example of shared responsibility.

Road Safety decisions should not be made in isolation but should be aligned with broader community values, such as economic; land use planning; human, occupational and environmental health; consumer goals; and mobility and accessibility as outlined in Scope of the Road Safety Problem. There is strong alignment between the Safe System and these goals. The following two case studies show how alignment of policies can be beneficial to safety.

The Safe System approach marks a shift from a sole focus on crash reduction to the elimination of death and serious injury. Well-established safety principles underpin the Safe System approach as set out in Key Developments. Further principles include the following:

As noted earlier, the Safe System approach builds upon the ground-breaking road safety efforts of the Netherlands and Sweden.

Wegman & Aarts (2006) outlines a set of guiding principles (based on the Dutch Sustainable Safety Vision) considered necessary to achieve sustainably safe road traffic. The principles are based on scientific theories and research methods arising from disciplines including psychology, biomechanics and traffic engineering, and are set out in Table 4.2 below.

| Sustainable Safety Principle | Description |

|---|---|

Functionality of roads | Single function of roads as either through roads, distributor roads, or access roads, in a hierarchically structured road network. |

Homogeneity of mass and/or speed and direction | Equality in speed, direction, and mass at medium and high speeds. |

Predictability of road course and road user behaviour by a recognisable road design | Road environment and road user behaviour that support road user expectations through consistency and continuity in road design. |

Forgiveness of the environment and road users | Injury limitation through a forgiving road environment and anticipation of road user behaviour. |

State of awareness by the road user | Ability to assess one’s task capability to handle the driving task. |

Tingvall (2012) commented on the challenges Sweden faces in redefining transport policy principles to reflect Vision Zero (or the Safe System approach):

“You can travel from A to B at 100 km/h and we will make some improvements to this two lane two way rural road to improve your travel safety:

“You can travel at this safe speed from A to B based on the safe system elements which are operating and which will avoid fatal and serious injury in the event of a crash. You can only travel faster if infrastructure safety is improved.” (eg, roundabouts at intersections, median barriers, run off road barriers to protect from roadside objects, etc.)

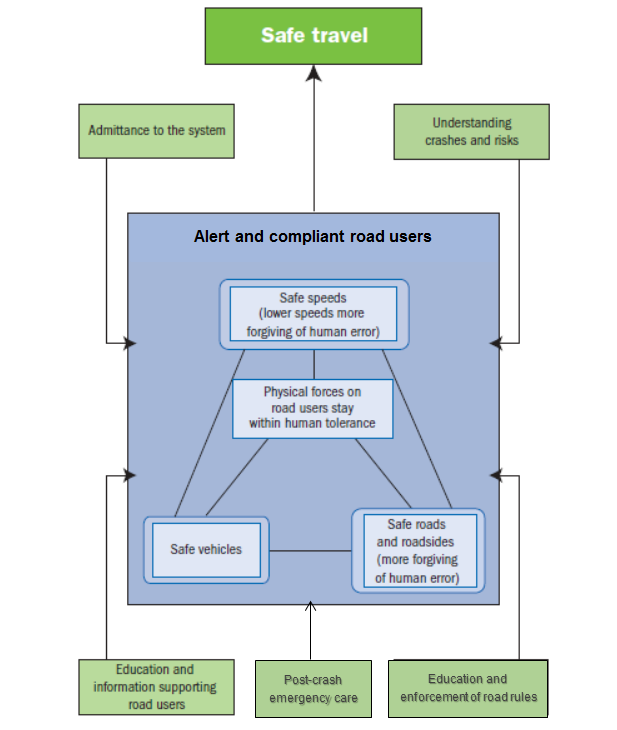

The elements of the integrated, human-centric Safe System model for safe road use and their interactions can be depicted as follows (Figure 4.1):

Figure 4.1: A model of the Safe System approach - Source: Adapted from OECD/ITF, 2008; ATC, 2009.

The Safe System design model has four main elements (including alert and compliant road users) plus five supporting activities that can be adjusted and applied in agreement with the four main elements to assist in making crashes more likely to be survivable.

The four main design elements are:

The key supporting Safe System elements include:

The last three elements in the list above support achieving road user compliance with the road rules.

In summary, for alert and compliant road users, a combination of vehicle safety features, safety characteristics of the infrastructure and travel speed are required, together with effective emergency medical post-crash care, in order to avoid a fatal or disabling serious injury outcome in the event of a crash.

Travel speeds are a critical variable within a Safe System with allowable safe speeds on any part of the network being dependent upon vehicle types (and their protective features), the forgiving and protective nature of the infrastructure and roadsides, the restrictions upon roadside access to the roadway and the presence of vulnerable road users. All of these factors will determine a maximum vehicle speed on each section of the network above which an unacceptable probability of death is likely from any collision.

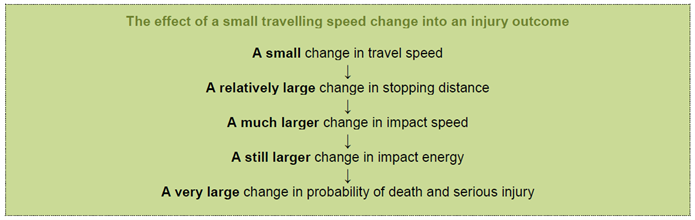

Injury outcomes and the creation of an inherently safe road system are largely dependent on the kinetic energy in the system. At the moment of impact, the force on the body can exceed the body's tolerance.

The amount of kinetic energy (Ek) is calculated according to the following formula:

Ek = 1/2 mv2

where m = mass (kg) and v = velocity (m/s)

The formula shows that kinetic energy does not increase linearly with speed, but with the square of the speed. This has important implications for how speed affects the road safety. A small increase in travel speed can significantly increase the probability of a serious injury outcome.

Source: Austroads (2018)

Reducing speed is one of the most effective ways to improve safety, saving lives and debilitating injuries. However, the opportunities that lowered travel speeds offer to other societal goals are generally under-appreciated. Reducing speed also generates multiple other benefits fundamental to sustainable mobility: reduced climate change impacts of road transport, increased efficiency (fuel and vehicle maintenance), improved inclusion and walkability (Job et. al. 2020)

Job et. al. (2020) highlighted that when taking into account the full range of economic impacts (GHGs, emissions, fuel, etc.), economically optimal speeds are lower than expected and typically lower than prevailing speed limits compared to limited evaluations of impacts based on travel time savings alone.

Speed management can be achieved through a range of interventions including road infrastructure and vehicle technology, as well as enforcement and promotion.

Crash outcomes, especially fatal crash outcomes, are influenced directly by the travel speed of vehicles at the time of impact.

Elvik et al. (2004) report that “Speed has been found to have a very large effect on road safety, probably larger than any other known risk factor. Speed is a risk factor for absolutely all accidents, ranging from the smallest fender-bender (crash) to fatal accidents. The effect of speed is greater for serious injury accidents and fatal accidents than for property damage-only accidents. If government wants to develop a road transport system in which nobody is killed or permanently injured, speed is the most important factor to regulate”.

Table 4.3 from Elvik et al. (2004) sets out the effects of variations in mean speeds on crashes of various severities. This relative change relationship applies on all lengths of road, over comparable periods of time and refers to the effects of changes in mean speed of travel of all vehicles.

| Relative change (%) in the number of accidents or victims | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in speed (%) | -15% | -10% | -5% | +5% | +10% | +15% |

| Accident or injury severity | ||||||

Fatalities | -52 | -38 | -21 | +25 | +54 | +88 |

Serious injuries | -39 | -27 | -14 | +16 | +33 | +52 |

Slight injuries | -22 | -15 | -7 | +8 | +15 | +23 |

All injured road users | -35 | -25 | -13 | +14 | +29 | +46 |

Fatal accidents | -44 | -32 | -17 | +19 | +41 | +65 |

Serious injury accidents | -32 | -22 | -12 | +12 | +25 | +40 |

Slight injury accidents | -18 | -12 | -6 | +6 | +12 | +18 |

All injury accidents | -28 | -19 | -10 | +10 | +21 | +32 |

Property damage only accidents | -15 | -10 | -5 | +5 | +10 | +15 |

Fatal crash outcomes are the crash type most affected by speed variation. As the above table shows, even small changes in speed (+5%) are associated with very large changes in the number of road crash fatalities (+25%).

As indicated in the safety principles above, an important way to reduce fatal or serious injury crash outcomes is through better management of crash energy, so that no individual road user is exposed to crash forces that are likely to result in death or serious injury.

Conditions that support limiting crash energy to levels below which fatal or serious injury crash outcomes are relatively unlikely, are now becoming better understood, but are still not well recognised or applied system-wide in most countries.

A key strategy is therefore to move (over time) to set posted speed limits in response to the level of protection offered by the existing (or improved) road infrastructure and the safety levels of the vehicles and vehicle mix in operation on sections of the network.

Mobility needs to be constrained by Safe System compliance. Future safe infrastructure investment will often be necessary before considering raising the speed limits on sections of the network in order to avoid increased fatalities or serious injuries.

McInerney & Turner state that the discipline of managing energy exchange and related forces currently exists in the fields of structural engineering for buildings and mechanical engineering for machines, but is rarely sighted in the design of roads. For infrastructure to provide the key building blocks for a Safe System, road engineering design practice worldwide must include provision for the management of kinetic energy. For example, there are simulation programs that examine an errant vehicle departure into a roadside environment, which calculate the change in kinetic energy as the errant vehicle encounters roadside hazards. The rate of kinetic energy dissipation can then be translated into differing collision severity potential.

While the Safe System approach has been adopted as the foundation of many countries’ road safety strategies, concept adoption and effective implementation are two different things. Implementation remains a considerable challenge.

The supporting enabler for planning, development and implementation of Safe System interventions is the road safety management system operating in any country (See Safety Management System for guidance).

The potential for road infrastructure safety treatments to provide certain and immediate reduction in crash likelihood and severity is well recognised. With adequate resources, infrastructure has the ability to eliminate nearly all fatal and serious crash outcomes. Many national and provincial road safety strategies have highlighted the role of infrastructure in making progress towards a Safe System.

Some examples of high-performing infrastructure treatments from these and other studies include typical findings (McInerney & Turner, in press; also see Intervention Option and Selection) that:

All road users need to be considered when designing or upgrading road infrastructure. This includes:

Netherlands Sustainable Safety in Safe System - Scientific Safety Principles and their Application outlined the important principle of safe travel speed which underpins a Safe System approach. Critical speed threshold levels in traffic crashes differ depending upon the type of crash being considered.

Table 4.4 presents the crash severity risk associated with travel speeds which are above a specific threshold level for key crash types. The crash types examined are vehicles with a pedestrian or other vulnerable road user, single vehicle side impact into a pole or tree, side impact between vehicles at intersections, head on crashes between vehicles and single vehicle run off road crashes.

| Impact speeds above which chances of survival or avoiding serious injury decrease rapidly | ||

|---|---|---|

| Crash Type | Impact Speed | Example |

Car/Pedestrian or Cyclist | 30 km/h | Where there is a mix of vulnerable road users and motor vehicle traffic |

Car/motorcyclist | ||

Car/Car (Side impact) | 50 km/h | Where there is a likelihood of side impact crashes (e.g. intersections or access points). |

Car/Car (Head-on) | 70 km/h | Where there is no separation between opposing traffic streams |

In certain parts of the transport network, such as high standard freeways, the risk of crash outcomes involving high levels of energy transfer (and therefore being fatal) is low in relation to the total distance traveled by vehicles on freeway standard links.

These freeways would typically have no at-grade intersections, would have median barriers installed to prevent head-on crashes, and side barriers installed to protect vehicle occupants from roadside objects, and would also segregate vulnerable road user activity such as pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists from higher speed traffic.

In these circumstances, and subject to limitations on vehicle flow volumes per lane, higher operating speeds (such as 100 or 110 km/h) can generally be safely supported for vehicles with a high standard of safety features.

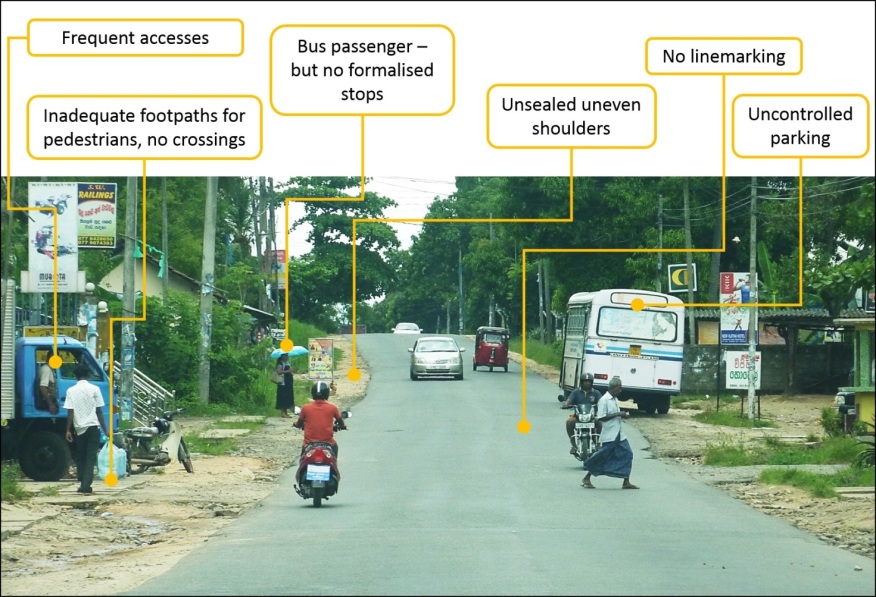

On the other hand, for two-lane, two-way roads in rural environments with unprotected roadside hazards, frequent intersections, unsealed shoulders and variable standards of horizontal and vertical geometry, the risks of serious casualty crash outcomes are much higher.

Table 4.4 illustrates that for these situations, even for a vehicle with the best currently available safety features, the road cannot support a travel speed much above 50 to 70 km/h if fatalities are to be avoided. If roadside hazards are protected (with barriers) and intersections are treated to reduce speeds to 50 km/h the travel speeds on the road can be 70 km/h. The addition of median barriers would enable higher operating speeds to be considered.

Where motorcycles are a large proportion of the traffic, lower speed limits, perhaps 40 km/h, may be necessary.

Lower speed in urban areas is also critical to improving road safety. Speed limits must be adapted to the prevailing traffic situation and to groups of different road users often using the same space. Complementary infrastructure measures such as speed humps and small roundabouts at key locations can help to ensure that speeds are controlled effectively to ensure that vulnerable road users are not exposed to impact speeds above 30km/h.

On higher-order urban arterial or distributor roads the function and use can be prioritised around achieving high traffic flows on road sections, whilst managing exchange at intersections or dedicated mid-block facilities. On these roads, vehicles can drive somewhat faster and tend to travel longer distances. Speed management on these roads should be supported by camera based (fixed or flexible) speed limit enforcement on corridors and at traffic lights. Pedestrians and cyclists can cross at intersections or dedicated mid-block facilities with appropriate localised speed management in place. Ultimately, the aim is to reduce exposure to high-speed motor vehicles, particularly at conflict points.

On the other hand, lower-order roads such as access roads must be managed to facilitate exchange between different road users at lower speed. Speeds in these areas and on these roads are low, not through police enforcement, but by traffic calming and speed management measures. In some areas it may be appropriate to limit vehicle access.

Below is a case study that illustrates the effectiveness of lowered speed limits in urban road environments.

The following four case studies from New Zealand, Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia show how each country is improving road safety. New Zealand uses a safe systems approach with Mexico, Paraguay and Slovenia using the iRAP to assess the risk on the road network to allow for safety plan and programme development.

Speed management is at the centre of developing a safe road system. Where infrastructure safety cannot be improved in the foreseeable future and a road has a high crash risk, then reviews of speed limits, supported by appropriate and competent enforcement to support compliance, are a critically important option. Support through targeted infrastructure measures to achieve lower speeds should be considered.

For example, lowering 100 km/h speed limits to 90 km/h may reduce mean speeds by 4 to 5 km/h if there is a reasonable level of enforcement. The scientific and evidence-based research shows that this will deliver a reduction of up to some 20% in the fatalities occurring on these lengths of roads (e.g. (Sliogeris, 1992). This of course assumes some enforcement support.

Since 1996, vehicle safety (or at least, car occupant safety) has been subjected to market forces rather than solely relying upon regulation throughout Europe through EuroNCAP (European New Car Assessment Programme). There is wide acknowledgment that this enhanced approach to advancing rapid development in vehicle safety has been successful. The automotive industry has reacted very quickly to the expectations of the market with regard to car occupant protection. Other New Car Assessment Programmes (NCAP) have been introduced in many regions and countries (Australasia, Japan and many more). The introduction of Electronic Stability Control/Programme (ESC or ESP) in vehicles has been very successful, with unexpected high effectiveness and a market penetration that is quicker than any other previous example (Tingvall, 2005). ESC is now a mainstream part of NCAP ratings.

The opportunities from new safety technologies in vehicles, which are now available or likely to become available, together with the level of inherent crashworthiness of many new vehicles in HICs are remarkable. These benefits should be sought by LMICs as an early priority. LatinCAP in Latin America and ASEAN NCAP are two examples of recent extension of NCAP to LMICs, which will arm consumers with safety information and drive market change. Furthermore, Global NCAP has recently been established and is likely to be highly influential.

Appropriate promotion of the benefits of safety features and overall vehicle safety levels needs to be carried out by road safety agencies. Road authorities should develop their awareness of these new vehicle safety features, particularly ways in which specific infrastructure treatments could leverage improvement in crash outcomes. Road safety agency actions (VicRoads, 2013) could include:

Progress with emerging technologies such as collision avoidance, intelligent speed adaptation, and inbuilt alcohol and fatigue detectors should be monitored by road safety agencies. Pilot studies have been conducted in many vehicle fleets internationally for research purposes in order to establish costs and benefits.

Other initiatives that countries need to pursue include:

Younger drivers should be made aware of the safest used vehicles available in the market in relevant price brackets to encourage their purchase and improve the chances of survival of young drivers in their higher risk early years of driving.

Developments in heavy vehicle safety include ESC responsive braking systems, and fatigue and speed monitoring equipment. New Truck Assessment Programmes may emerge in coming years for heavy vehicle prime movers. Again, road safety agencies need to be aware of these developments.

Many opportunities for improvement exist in the vehicle safety features available to LMIC markets. There are reports of vehicles imported from other countries without safety features fitted, which are standard inclusions in the automobile supplier’s home market (this is reportedly in an endeavour to limit costs). Some countries impose higher rates of tax on safety equipment in vehicles as a misplaced luxury item revenue raising measure, which discourages their fitment. Some key issues are:

© ARRB Group

Maximising road user behaviour that is compliant with road rules remains an important issue. This requires the presence and active implementation of effective legislative arrangements; data systems for vehicles, driver licensing and offences (and their linkage); enforcement; justice system support; and offence processing, as well as follow-up capacities.

Human error, rather than deliberate illegal behaviour, is an important contributor to fatal and serious crashes. Measures to reduce the prospect of human error need to be taken to guide use of the network. Clear consistent guidance and reasonable information processing demands upon the road users along a route is necessary to reduce uncertainty and indecision. These issues are discussed in detail in Design for Road user Characteristics and Compliance, but key issues include:

Developing a respected and effective police enforcement capability requires high-level management competence, good standards of governance, quality research to guide efforts, and a strong results focus.

Progress in LMICs will depend heavily on substantial expert support to accelerate a ‘learning by doing’ approach. A key thread running throughout this manual is practical guidance concerning the implementation of the Safe System approach. A suggested path for road safety agencies in LMICs for moving from weak to stronger institutional capacity, by implementing effective practice through demonstration programmes (or projects), is outlined in Road Safety Targets, Investment Strategies, Plans and Projects. The programmes should include area-based projects involving all relevant agencies and some national level policy reviews. This approach will support the production of steady improvement in road safety results from all agencies.

Development of a more complete understanding and uptake of a Safe System approach, after adoption as official policy by a country, will take time. It will rely upon a continuous improvement process that examines and implements options, often in innovative ways, to improve performance.

While the key principles of a Safe System are well established (OECD, 2008 and 2016) and underpin the UN Global Plan for the Second Decade of Action for Road Safety (WHO, 2021), the challenge now is to translate these aspirations into practical policy implementation. This is especially important in low-and middle-income countries, where the burden of road injury is highest.

A joint International Transport Forum - World Bank Working Group on "Implementing the Safe System" has developed a theoretical framework to guide those seeking to implement the Safe System approach (ITF, 2022). The framework describes how to improve safety across each of the Safe System pillars through the various key components of a Safe System