8.4 Ensuring Application in Practice

Human Factors issues are not as well catered for as they should be on most of the world’s roads, including those in HICs. A number of major in-depth crash investigations were carried out in the 1960s and 1970s that implied that driving actions carried out by the road user as the main contributing factor in most crashes. More recently, it has come to be understood that many of these driving mistakes were as much due to deficiencies in the road system as to failings on the part of the driver. These included crashes due to inadequate sight distance, poor lighting at critical points, poor transition zones, insufficient management of the field of view as well as misguiding drivers expectations and road surfaces that provided less friction than the driver was expecting.

HICs may therefore have a large backlog of road deficiencies to rectify to ensure that Human Factors needs of users are adequately integrated in their design standards and the practice to treat black spots and black lines across their networks. The same is likely to be true for LMICs. However, the road system cannot be brought up to standard unless the basic design tools – the road design standards and guidelines – take account of these issues. The PIARC study (PIARC, 2012b; PIARC, 2016) suggests that there is a long way to go before this can be achieved.

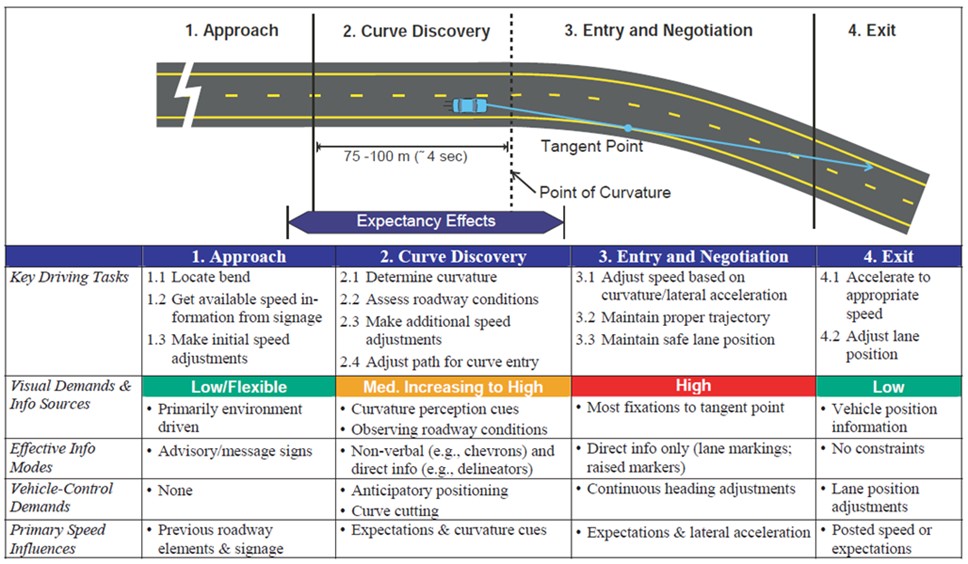

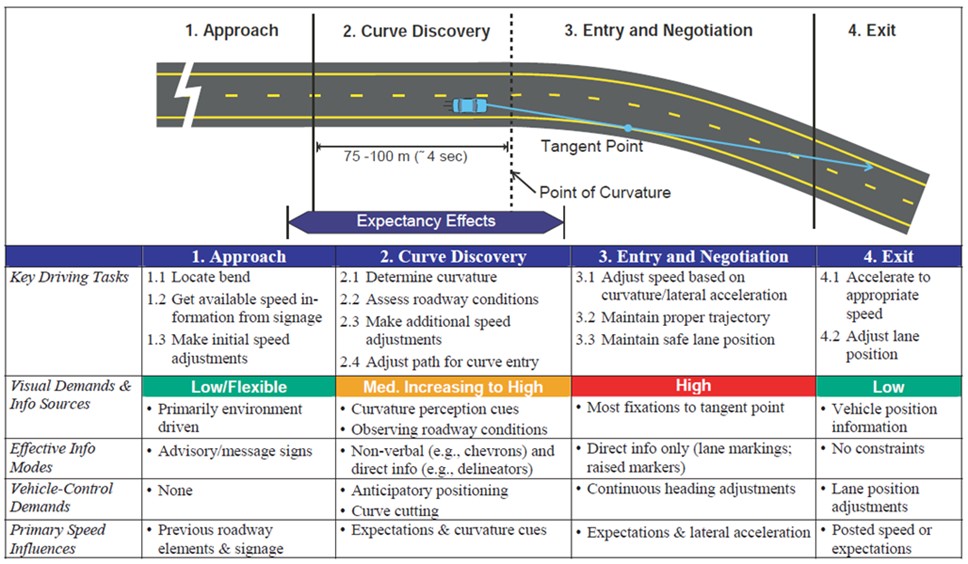

The driver demands associated with navigating a curve can serve as an example of how analyzing driver tasks can be helpful in understanding how road design impacts driver performance. Figure 8.21 describes the activities that driver would typically perform while navigating a single horizontal curve (Campbell et al., 2012). From Campbell's example, tasks like maintaining speed and lane position while entering and following the curve are more demanding and challenging and the driver needs to pay closer attention to basic vehicle control and visual information acquisition. Task analysis identifies the key information and vehicle control elements in different parts of the curve driving task.

Figure 8.21 illustrates how and when driver demands are influenced by design aspects such as design consistency, degree of curvature, and lane width. In particular, identifying highly demanding (or high workload) components of the curve driving task provide an indication of where drivers might benefit from information regarding delineation or benefit from the elimination of potential visual distractions.

An expert Human Factors group examined the design standards from nine HICs and LMICs from across the world and systematically compared the advice and procedures in each standard with the specific Human Factors requirements which arise from the three Human Factors requirements described in the PIARC HFPSP guide (see Section 8.2). Requirement No.1, giving the driver sufficient time to react, was best catered for, with the specific driver needs being fully discussed in 49% of cases. Requirement No. 2, ensuring the road provides a safe field of view, was least well catered for, the specific needs being fully discussed in only 9% of cases. Requirement No. 3, that the road matches the road users’ expectations, was fully discussed in 34% of cases.

It therefore appears that much work remains to be done to bring the world’s design standards up to a level where Human Factors issues are fully addressed and to bring the thinking of designers along with them. In lieu of design standards that embed Safe System principles. Road Safety Audits provide a valuable means of evaluating the safety performance of road designs with consideration of Human Factors issues. Case studies from Canada and Iran present Road Safety Audits.

CASE STUDY – Canada: Recreational Lakeside Re-development Project (Feasibility State Road Safety Audit)This case study example presents the results of a feasibility stage RSA that was conducted for a community in British Columbia, Canada. The project involved the review of a conceptual design of a lakefront area to improve the mix of transportation modes, access requirements and traffic management to better serve the citizens of the community and the many tourists that frequent the area.

Read more (281kb).

CASE STUDY – Iran: Case Study Road Safety Audit Report of Qom-Garmsar Freeway (Pre-Opening Stage RSA)This case study example presents the results obtained from a road safety audit project for the Qom-Garmsar Freeway. The RSA was a Pre-Opening RSA, completed before the freeway is opened to confirm that the facility provided would provide an acceptable safety performance based on the road signs and markings, safety equipment and police checkpoints.

Read more (273 kb).

Pathway to Effective Design for Road User Characteristics and Compliance

Getting started

- Establish design standards and guidelines that incorporate established knowledge of Human Factors.

- Where design standards already exist, review standards to ensure that current understanding of Human Factors is fully integrated with the needs of transition and reaction time, the management of the field of view and a reliable pre-programming of driver's expectations.

- Provide training for design, road operations and road management staff in Human Factors and Safe System principles, supported by Human Factors guidelines.

- Provide basic training for police and other enforcement officers in the Safe System and evidence-based enforcement principles and methods.

- Prepare a manual on signs and line markings which covers most of the frequently encountered situations, drawing on experience and examples from elsewhere.

- Obtain general agreement about the importance of speed management in achieving Safe System outcomes.

- Establish road rules that are easy to understand and are consistent with driver expectations.

Making progress

- Application of standards and guidelines to the design of new facilities and upgrading of old facilities.

- Creation of self-explaining roads that are matched to their function.

- Hazardous spot/road section treatment according to human factors principles

- Establishment of standards for assets, both for new assets and for assets in-service based on road users’ ability to cope with different levels of asset condition; e.g. road surface characteristics, sign and road marking condition.

- Establishment of effective school education programmes to teach appropriate road use, tailored to the needs of individual age groups; priority should be given to child pedestrian training in elementary schools.

- Establishment of effective publicity programmes to address clearly defined behaviours, targeted at the key groups at risk; these programs should be designed to prepare road users for and to reinforce enforcement

- Revise training and testing procedures for new drivers along graduated licensing lines.

- Establishment of enforcement programmes addressed at specific high-risk behaviours, guided by intelligence on where and when it occurs.

- Ensure increased compliance with line markings, sign and signal controls.

- Ensure increased seatbelt wearing; and reduced drink driving, fatigued driving and speeding.

Consolidating activity

- Achieving consistency in design standards, signage and pavement markings across the road network.

- Training road safety auditors in Human Factors principles, and application of these principles to road safety audits.

- Extension of self-explaining roads across the network.

- Continual progress towards a road system that meets Safe System requirements.

- Comprehensive testing of new types of treatments before installation and evaluation after installation.

- Creation of a comprehensive inventory of road assets and their condition, accompanied by a programme to ensure all assets are kept up to the established standards.

- Maintenance of age-appropriate road safety programmes throughout the pre-school and school years to develop safe pedestrian behaviour and prepare for later road use.

- Maintenance of effective publicity programmes in response to fluctuating patterns of high-risk behaviours to coordinate with enforcement activity.

- Maintenance of high levels of enforcement.

- Ensure that non-compliance with line markings, sign and signal controls is a rare exception.

- Non-wearing of seatbelts, fatigued driving, drink driving and high-level speeding should be reduced to very low levels and moderate speeding is reduced.